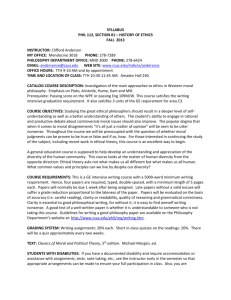

The Great Ideas of Philosophy, 2 nd Edition Part I Professor Daniel

advertisement