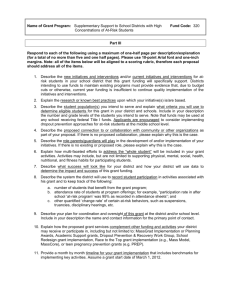

CAMBODIA SECONDARY EDUCATION STUDY: Educational

advertisement