Estimating the Effects of Private School

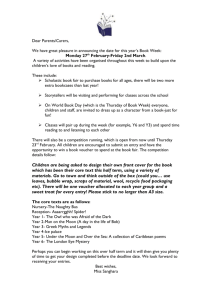

advertisement

Estimating the Effects of Private School Vouchers in Multi-District

Economies*

Maria Marta Ferreyra

Graduate School of Industrial Administration

Carnegie Mellon University

March 20, 2003

Abstract

This paper estimates a general equilibrium model of school quality and household residential

and school choice for economies with multiple public school districts and private schools. In the model,

households have heterogeneous religious preferences, and private schools can be either Catholic or

non-Catholic. The model is estimated with 1990 data from large metropolitan areas in the United

States, and the estimates are then used to simulate two large-scale private school voucher programs in

the Chicago metropolitan area: universal (non-targeted) vouchers, and vouchers restricted to nonCatholic schools. The simulation results indicate that both programs increase private school enrollment,

and affect household residential choice, with the largest school quality and welfare gains accruing to

low-income households. Universal vouchers increase enrollment at both Catholic and non-Catholic

private schools, yet when vouchers are restricted to non-Catholic schools, the overall private school

enrollment expands less at moderate voucher levels, and enrollment in Catholic schools tends to

decline, relative to the non-voucher equilibrium, as the dollar amount of the voucher increases. In

addition, fewer households benefit from non-Catholic vouchers.

*

This paper is based on my PhD dissertation at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. I wish to thank my advisors

Derek Neal, Steve Durlauf and Phil Haile for their guidance and encouragement. I am also grateful to Peter

Arcidiacono, Dennis Epple, Arthur Goldberger, John Kennan, Yuichi Kitamura, Bob Miller, Tom Nechyba,

Richard Romano, Ananth Seshadri and Holger Sieg for many helpful ideas and suggestions. I owe special thanks

to Grigory Kosenok for his help with the technical aspects of this project and for many insightful conversations. I

have also benefited from conversations with Oleg Balashev and Hiroyuki Kasahara, and wish to thank seminar

participants at Brown, Carnegie Mellon, Columbia Business School, Duke, Rutgers, U. of Illinois at UrbanaChampaign, Virginia, and Wisconsin, and participants at the 2002 CIRANO conference on education, at Camp

Resources X, and at the Stanford Conference on Empirical Boundaries for IO, Public Economics and

Environmental Economics, for their questions, comments and suggestions. I am grateful to the UW-Madison

Condor Team from the Computer Science Department, and in particular to Peter Keller, whose help has been

essential to carry out this project. Financial support from the UW Department of Economics to purchase data, and

from the UW Robock Award in Empirical Economics are gratefully acknowledged. All errors are mine.

1. Introduction

Vouchers play a central role in the debate about education reform in the United States.

Vouchers, it is argued, give households the opportunity to enroll their children in private

schools and access the type of education that they prefer for their children. Currently, many

households opt out of the public school system to send their children to private schools that

better meet their demands. These households pay private school tuition in addition to the

property taxes used to support local public schools. However, some households prefer private

schools over the public schools in their metropolitan areas, but face budget constraints that

restrict them to public schools.

Although public schools have no explicit tuition, there are costs associated with the

choice of public schools where residences and public schools are linked. In these places,

households must choose public schools and residences as bundles, whose costs are determined

by housing prices and property taxes. Therefore, in order to gain access to their preferred

public schools, households might choose to live in places they would not have selected in the

absence of bundling.

Vouchers, it is claimed, would break this bundling by allowing

households to choose private schools, which have no residence requirements.

Thus, vouchers may not only give households more school choices, but also alter

household residential decisions. As a result, public school districts may experience changes in

their property values, school funding, and the composition of their student populations. To

gain insight into the potential impact of large-scale private school voucher programs, these

general equilibrium effects should be examined.

In this paper I estimate a general equilibrium model that jointly determines school

quality and household residential and school choices within an economy with multiple public

school districts and private schools. I then use the parameter estimates to simulate two

different voucher programs.

Although models of household sorting across jurisdictions originated in 1956 with

Tiebout’s work, few attempts have been made to estimate them (Bayer (2000), Epple and Sieg,

(1999), Epple, Romer and Sieg (2001)). In particular, while researchers who have evaluated

the general equilibrium effects of vouchers have relied on calibration to simulate voucher

experiments (Epple and Romano (1998, 2000), Fernandez and Rogerson (1998, 2001), Glomm

and Ravikumar (1999), Nechyba (1999, 2000)), I use estimates to simulate such experiments.

2

The few voucher programs enacted to date in the U.S. have included a small number of

voucher recipients, and have often restricted the set of eligible private schools. As a result,

researchers have no data to evaluate the general equilibrium effects of potential large-scale

voucher programs, and therefore must turn to simulation to investigate them. In this context,

structural estimation using data from settings without vouchers can prove particularly helpful

by providing parameter estimates that capture the behavior of households and schools. The

parameter estimates can then be used to evaluate the general equilibrium effects of

hypothetical large-scale voucher programs.

One school attribute demanded by numerous households is religious education.

According to the 1989 Private School Survey, 85% of the private school enrollment in grades

9 through 12 was in religious schools. Moreover, the considerable variation in private school

markets among metropolitan areas is related to geographic differences in the distribution of

adherents to various religious denominations.1 In other words, to understand how private

school markets differ across metropolitan areas, and how voucher effects may differ

accordingly, the consideration of religious preferences appears to be relevant. Nevertheless,

previous research on the general equilibrium effects of vouchers has not incorporated religious

preferences as a determinant for the existence of some private schools.

Thus, I extend Nechyba’s (1999) theoretical work to include household religious

preferences and two types of private schools, Catholic and non-Catholic. Moreover,

households of a given religion in the model vary in their taste for each type of private school;

for instance, some Catholics like Catholic schools better than others. The inclusion of religion

in the model has important implications for voucher effects. For example, even among

households with the same endowment level, those with a high preference for Catholic schools

derive large rewards from vouchers relative to those with a weaker preference. In other words,

religious preferences affect the distributional effects of vouchers. In addition, a contentious

issue related to publicly-funded vouchers is their use to underwrite tuition at religious

schools.2 By including religious preferences and schools, the model I employ is able to

consider the effects of banning voucher use in religious schools.

Among private schools, I focus on Catholic schools for several reasons. First, Catholic

schools are the largest and most homogeneous group of schools within the private school

1

See Section 2 for more details.

The Supreme Court recently upheld voucher use at religious schools in the Cleveland voucher program. See the

Supreme Court’s ruling on Zelman v. Simmons-Harris (06.27.02).

2

3

market.3 Second, in states where it has been debated whether religious schools should be

eligible to participate in voucher programs or not, most of the students attending religious

schools are enrolled in Catholic schools. Third, the majority of the current voucher proposals

attempt to provide choices for low-income students in inner cities where Catholic schools have

historically had a strong presence, often times targeting economically disadvantaged students

through subsidized tuition and privately-funded vouchers.

To estimate the model I use a minimum distance estimator with 1990 data on the

metropolitan areas of New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, Detroit, Boston, St. Louis, and

Pittsburgh. In 1990 these areas were among the twenty largest metropolitan areas in the United

States, had a high level of dependence on local sources for public school funding and had

Catholic populations proportionately larger than the national average. To estimate the model, I

created a rich dataset that combines sources such as the 1990 School District Data Book, the

1989 Private School Survey, and the 1990 Churches and Church Membership in America

survey. The estimation strategy consists of simulating the equilibrium for each metropolitan

area and alternative parameter points, and then choosing the point that minimizes a welldefined distance between the data simulated from the model and the observed data.

Since there is no closed form solution for the equilibrium, the only available

mechanism for obtaining the predicted equilibrium for each parameter point is the simulation

of the equilibrium for each metropolitan area and parameter point. This paper is one of the first

attempts to use this procedure. It is a computationally intensive technique, but capable of

dealing with the simultaneity of the variables jointly determined in equilibrium. Although

many simplifications are needed in order to make the problem tractable, my estimates succeed

at capturing the pattern of income stratification, and the distribution of housing values across

districts within a metropolitan area. In addition, they replicate private school enrollment

patterns for large school districts quite well.

Currently, I have assessed the effects of two hypothetical policies, the introduction of

universal vouchers, and of vouchers for non-Catholic private schools. Although universal

(non-targeted) vouchers have not been implemented to date and most of the current voucher

proposals feature targeted vouchers, the analysis of universal vouchers gives insight into the

impact of an unrestricted voucher program, which is helpful given that any other program may

3

According to the 1989 Private School Survey, 58% of private school enrollment in grades 9 through 12 in

secondary and combined schools was in Catholic schools, 27% in other religious schools, and the remaining 15%

in non-sectarian schools in the United States in 1989. When restricted to secondary schools, the same survey

reports that Catholic schools captured 75% of the total private school enrollment.

4

be seen as a restricted version of universal vouchers. In addition, the simulation of vouchers

that may not be used for Catholic schools (“non-Catholic vouchers”) is particularly important

in light of the controversy over the legality of state-funded vouchers for private religious

schools, and of the Supreme Court’s ruling that the use of vouchers for religious schools does

not violate the Constitution. Therefore, when designing voucher programs, states can choose

whether or not to include religious schools.4 In view of this, the analysis of the general

equilibrium effects and welfare implications of not allowing vouchers for religious schools is

particularly pertinent. I simulate these policies for the Chicago metropolitan area, where 40%

of the population is Catholic and almost half of the population resides in the central district.

My simulation results indicate that universal and non-Catholic voucher programs

produce some qualitatively similar effects. Both increase private school enrollment, and both

affect where households choose to live. When the dollar amount of the voucher is low, both

vouchers provide incentives for some middle-income households from good public school

districts to migrate into districts where lower housing and public school quality is reflected in

lower property prices, and enroll their children in private schools. This result indicates that

vouchers may indeed break the bundling of residence and public schools. In addition, it

provides evidence that vouchers may attenuate the residential stratification generated by the

residence-based public school system.

While middle-income households use vouchers even when the dollar amount is low,

households in low-income districts only use them when the voucher level is above the aid per

student provided by the state to those districts. Yet, as the dollar amount of the voucher

increases, both high and low-income households adopt vouchers, and private schools arise in

poor and wealthy districts alike. Voucher availability reduces the housing premium in the best

public school districts but increases it in the others, thus causing capital losses or gains,

respectively, to the households in those places.

Both voucher programs induce comparable improvements in average school quality. In

addition, the largest proportional school quality gains accrue to low-income households.

Although public school quality falls in these simulations, these losses are spread throughout all

districts, and are more severe for the best districts as the voucher level grows. Interestingly, at

low and moderate voucher levels some households that remain in public schools also benefit

from the introduction of vouchers.

4

In certain states, allowing voucher money to be used for religious schools would require a change in the state

Constitution, as in the case of Michigan. See Mintrom and Plank (2001).

5

Both programs have redistributive effects. Since in these simulations vouchers are

funded with a state income tax, they tend to benefit the poor relative to the wealthy. Because

of the fiscal burden and capital losses, the average household that loses welfare under vouchers

is wealthier than the average winner. In addition, the average welfare change induced by each

program is small, yet the distributional effects are large. In both cases, low-income households

experience the largest gains relative to endowment (around 5%).

Although the programs are similar in the aforementioned effects, they are dissimilar in

others. The dissimilarities derive from the fact that a voucher program restricted to nonCatholic private schools changes the relative price of Catholic schools. This, in turn, may

induce some households, depending on their religious preferences and budget constraints, to

substitute non-Catholic private schools for Catholic schools. For example, consider a highincome Catholic household with a strong preference for Catholic schools that would attend

Catholic schools even without vouchers. Only a sufficiently high voucher level would induce

this household to enroll in a non-Catholic private school. On the other hand, consider a

Catholic household that only slightly prefers Catholic over non-Catholic schools, and whose

budget constraint does not permit it to choose private schools without vouchers. Even a

relatively low voucher level would induce this household to enroll in a private non-Catholic

school.

Vouchers that are targeted exclusively for non-Catholic schools reduce the extent of

private school enrollment and voucher use at moderate voucher levels, because many of the

households that would use vouchers if they were universal have a strong preference for

Catholic education. Moreover, whereas enrollment grows in all private schools under universal

vouchers, it grows at private non-Catholic schools but declines at Catholic schools under nonCatholic vouchers. At a sufficiently high level, universal and non-Catholic vouchers are used

at the same rate.

More households benefit from universal vouchers than from non-Catholic vouchers.

Furthermore, at least 20% of all households win under universal vouchers, yet lose under nonCatholic vouchers. These are households with a strong preference for Catholic schools, that

either attend Catholic schools in the absence of vouchers or choose them under a universal

voucher. As their average welfare gains drop between 2 and 4% of their wealth, these are the

households that experience the largest welfare change across voucher regimes. Furthermore,

whereas Catholic households gain the most relative to their wealth at each endowment level

under universal vouchers, they lose the most under non-Catholic vouchers.

6

The above results use structural estimates from a general equilibrium model and

provide insight into voucher policies. As such, my work contributes to several lines of

research. While this paper broadly complements the literature on school choice, it relates more

closely to research that evaluates the general equilibrium effects of vouchers in multi-district

settings (Nechyba (1999, 2000), Fernandez and Rogerson (2001)). In addition, my work

complements the literature that estimates general equilibrium models for multi-district

economies. For instance, Epple and Sieg (1999) estimate an equilibrium model of local

jurisdictions for the metropolitan area of Boston, and test the model’s predictions about the

equilibrium distribution of households across communities. However, their framework does

not include private schools, nor does it include multiple neighborhoods within jurisdictions.

Since the central districts of the largest metropolitan areas display a wide variety of housing

quality and neighborhood amenities that induce household sorting within districts, it seems

important to account for that variety in the model and the estimation. My work accomplishes

this task.5 Bayer (2000) estimates an equilibrium discrete choice model of residential and

school (public vs. private) decisions of households with elementary school-aged children in

California, in an attempt to clarify what drives the observed differences in school quality

consumption across households. Although private schools are included in his model, the

specific mechanisms by which they arise are not modeled. In contrast, such mechanisms are

part of the model presented in this paper. Additionally, the public school financial setting in

California permits the researcher to ignore the public choice process which funds public

schools,6 but this is not appropriate for metropolitan areas located in many other states where

property taxes are indeed endogenous. By allowing taxes to be determined by majority voting

rule, my work is suited to explore voucher issues in a wide variety of metropolitan areas and

public school financial regimes.7

This paper is organized as follows: section 2 provides descriptive statistics that

highlight the income-sorting of households among districts and the geographic variation in

private school markets among the metropolitan areas of interest. Section 3 presents the model.

5

While Nechyba (1999 and 2000) includes multiple neighborhoods within a given district, my research is the first

attempts to do so in an estimation setting.

6

In California, districts are fiscally dependent – namely, they do not rely on their own resources to fund their

schools. Counties levy property taxes, whose rate is legally limited to 1%. These revenues are then redistributed

by the state to the districts according to a legislative formula. In practice, California’s system resembles full state

funding.

7

In an extension of Epple and Romer (1999), Epple, Romer and Sieg (2001) investigate whether observed levels

of public expenditures satisfy the necessary conditions implied by majority rule in a general equilibrium model of

residential choice.

7

Section 4 discusses the computable version of the model used for estimation purposes. Section

5 presents the data sources, section 6 describes the estimation procedure, and section 7

discusses the estimation results. Section 8 analyzes voucher effects in policy simulations, and

section 9 concludes.

2. Descriptive Statistics

My analysis focuses on the metropolitan areas of New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, Detroit,

Boston, St. Louis, and Pittsburgh. As of 1990, these areas were among the twenty largest

metropolitan areas in the United States, had a high level of dependence on local sources for

public school funding8 and had populations that were at least 25% Catholic. Ferreyra (2002)

describes in detail how these metropolitan areas were selected, and Table 1 lists some of their

relevant features. My analysis focuses exclusively on secondary and unified school districts.9

The school districts in these metropolitan areas, however, are far from homogeneous,

as shown by the summary statistics in Table 2.10 Large variation occurs in the fraction of

households with children in private schools, in average household income, and in average

housing rental value.11 Moreover, households with children in private schools tend to have

higher incomes and to live in houses with higher rental values than households with children in

public schools. From the point of view of public school finance, districts also differ widely in

their average spending per student and, to some extent, in their sources of public school

funding. While some of the variation among districts is driven by the fact that they belong to

8

Public school districts fund their operations through a mix of local (district level), state, and federal resources,

yet the share of each of these sources varies among metropolitan areas and districts.

9

As will be seen in Section 4, two of the simplifying assumptions made are: (1) public school funding mostly

relies on local property taxes, and is supplemented by a state flat grant per student, and (2) households in the

population are indifferent between public and non-Catholic private schools. While computational reasons explain

the imposition of both assumptions, (1) is also motivated by the extreme difficulty of replicating the actual public

school funding regimes with stylized formulas (see Section 2.4 for further discussion on this issue). Assumption

(2) is particularly restrictive with respect to religious non-Catholic households, many of whom may prefer schools

of their denomination over public schools. Thus, this assumption renders the model inappropriate to explain the

formation of such schools. However, given the need to impose assumptions (1) and (2), I select metropolitan

areas where public schools are indeed predominantly funded by local property taxes, and where most of the

population is Catholic. This selection criteria yields a set of metropolitan areas with high private (and Catholic)

school enrollment where proposals for publicly funded private school vouchers, and even privately funded

voucher programs, have flourished over the last ten years.

10

Summary data on households and enrollment pertains to grades 9 through 12.

11

The calculation of housing rental values is described in Ferreyra (2002).

8

different metropolitan areas, heterogeneity among districts also occurs within metropolitan

areas, providing evidence that households sort themselves non-randomly across jurisdictions.

In the metropolitan areas included in my sample, the inner city district is the largest

one, and is comprised of multiple neighborhoods with different housing qualities and

geographic amenities. The fraction of households with children in private schools is relatively

high in the inner city district and in some suburban districts. Households that live in inner city

districts and send their children to private schools include middle-income families who reside

in the district’s most expensive neighborhoods, and low-income families whose children

attend private schools with subsidized tuition.12

The evidence presented so far indicates that factors such as the distribution of housing

quality within and across districts and income distribution are related to private school

enrollment. In addition, Table 3 shows that religion is connected to private school enrollment.

Among the twenty largest metropolitan areas in the United States, those with a higher fraction

of students in private schools also have a higher fraction of private school students enrolled in

Catholic schools. Furthermore, these metropolitan areas have a higher fraction of Catholics,

and the correlation between the fraction of students enrolled in Catholic schools and the

fraction of Catholics is positive and high. Thus, the geographic variation in private school

markets also seems to be shaped by the geographic variation in the distribution of adherents to

different religions.

To summarize, the selected metropolitan areas display significant variation in the

dimensions of interest. The data also provides evidence of household sorting across districts

and into schools, and highlights the factors associated with this sorting. Thus, the model

presented in the next section captures all these elements.

3. The Model

In this section, I provide a theoretical model of school quality and household residential

choice.13 A computable version of the model aimed to simulate voucher experiments is

presented in the next section. In the model, an economy is a set of school districts that contain

neighborhoods of different qualities. There are three types of schools: public, private Catholic,

12

This is because numerous inner-city religious schools subsidize student tuitions. Often families do not belong

to the denomination of their children’s private school.

13

This is an extension of Nechyba’s (1999) model including household religious preferences and different types

of private schools.

9

and private non-Catholic. The economy is populated by households that differ in their

endowment level and religious preferences, yet maximize utility by choosing a location and a

school for their children. A school’s quality is endogenously determined by the average peer

quality of the school’s students and the spending per students. Public schools’ spending is

supported by a local property tax set by majority rule. Private schools, in turn, are modeled as

clubs formed by parents that set admission requirements based on peer quality and share the

school’s costs equally.14 Furthermore, the parental valuation of a school’s quality depends on

the match between the school’s religious orientation and the household’s religious preferences.

In equilibrium, no household wants to move, switch to a different school, or vote differently.

Households and Districts

The economy is populated by a continuum set of households N. Each household n ∈ N is

endowed with one house. Hence, N also represents the set of houses in the economy, which is

partitioned into school districts. Every district d is in turn partitioned into neighborhoods. The

set of houses in neighborhood h and district d is denoted by C dh , and C d denotes the set of

houses in district d. Houses may differ across neighborhoods, but within a given neighborhood

are homogenous and have the same housing quality and rental price.

Each household has one child, who must attend a school, public or private. One public

school exists in each district, and the child may attend only the public school of the district

where the household resides. If parents choose to send their child to a private school, Catholic

or non-Catholic, they are not bound to any rule linking place of residence and school.

In addition to a house, households are also endowed with a certain amount of income,

and there are I income levels. Households also differ in religious orientation, given by their

valuation of Catholic schools relative to non-Catholic schools. A household has one of K

possible religious types, where types 1,K, L are Catholic, and the others non-Catholic. Not all

the L Catholic types are necessarily identical, for they may differ in their relative valuation of

14

A club is a voluntary coalition of agents that derive mutual benefits from production costs, members’

characteristics, or a good characterized by excludable benefits – i.e., a good for which there is a mechanism that

prevents agents outside the club from consuming the good (Cornes and Sandler, 1996). Private schools fit this

description well, as parents freely join them and share the school’s cost through tuition payments. In addition,

they also share the characteristics of the student body at the school, and the educational services produced by the

school.

10

Catholic schools, and the same is true for the non-Catholic types.

Household preferences are described by the following Cobb-Douglas utility function:

U (κ , s, c) = s α c β κ 1− β −α , κ = k dh

(1)

where α , β ∈ (0, 1) , kdh is an exogenous parameter representing the inherent quality of

neighborhood h in district d, c is household consumption, and s is the parental valuation of the

quality of the school attended by the child, which, in turn, depends on the household’s

religious preferences. Household n seeks to maximize utility (1) subject to the budget

constraint:

c + (1 + t d ) p dh + T = (1 − t y ) y n + p n

(2)

where yn is the household’s income, ty is a state tax rate, and pn is the rental price of the

household’s endowment house. Given its per-period total income, represented by the righthand side of (2), the household chooses to live in a location (d , h) with housing price pdh and

local property tax rate td. It also chooses a school for its child with tuition T. Since public

schools are free, T = 0 in this case. Remaining income is used for consumption c.15

Production of school quality

All school types produce school quality ~

s according to the Cobb-Douglas production function:

~

s = q ρ x1− ρ

(3)

where ρ ∈ [0,1] , q stands for the school’s average peer quality, and x is spending per student at

the school. Denote by S the set of households whose children attend the school, and by y (S )

the average income of these households, y ( S ) = ∫ y n dn µ (S ) , where µ (S ) is the measure of

S

set S. Then the school’s average peer quality is defined as q = y (S ) .16 The spending per

student x equals tuition T if the school is private, and it equals the spending per student in

15

Note that if the household chooses to live in its endowment house, then (2) becomes

c + t d p n + T = (1 − t y ) y n , i.e. the after-tax income is spent on consumption, property taxes, and school

tuition.

16

The empirical findings on peer effects in education are quite varied, and there is no consensus on how peer

effects operate nor at which level (school, class, group of students within a class). Thus, theoretical models

usually pick a simple specification of peer effects that agrees with some of the empirical evidence. The current

model agrees with evidence that peer effects act primarily through parental involvement and monitoring of

schools, both of which increase with income (McMillan (1999)).

11

district d, xd, if the school is public and run by the local government.

The value that parents assign to school quality is represented in utility function (1) by

the variable s, and depends on their religious preferences. A household of religious type

k = 1,K, K whose child attends a school with religious orientation j = 1, 2 (Catholic or nonCatholic respectively)17 and quality ~

s j perceives the school quality as follows:

s kj = Rkj ~

sj

(5)

where Rkj > 0 is a preference parameter. Households of a given religious orientation may have

different tastes for Catholic and non-Catholic schools.

Public Schools

Let N pub be the subset of all households N in the economy that choose to send their children

to public schools, and define J d as the population residing in district d. The set N

pub

∩ J d is

then the set of all households residing in district d that choose public school for their children.

s = q ρ x1− ρ , where q is the average

The quality of the public school in district d is ~

d

d

d

d

income of households with children attending this school, q d = ∫

N

pub ∩ J d

y n dn µ (N

pub

∩ Jd ) .

Under a regime of local financing, the public spending in education is funded by local property

taxes, possibly aided by the state. Thus, the spending per student in district d is given by

xd = t d Pd µ (N

pub

∩ J d ) + AIDd , where AIDd is the amount of state aid per student for

district d, funded through a state income tax, and Pd = ∑ µ (C dh ) p dh is the local property tax

h

base.

Private Schools

Private schools are modeled as clubs formed by parents under an equal cost-sharing rule.

Because of the constant returns to scale of technology to produce education (see equation (3))

and the absence of fixed costs to open a private school, households of a given endowment type

have incentives to segregate themselves into a private school and reject lower endowment

17

Public schools are nonsectarian and, therefore, non-Catholic.

12

types. Therefore, a private school formed by households of income level yn has a peer quality

q = yn .

Parents of a given endowment who wish to set up a private school can choose to found

either a Catholic or a non-Catholic school. Households care about the makeup of the student

body because of peer quality and other households’ willingness to pay. However, households

do not care about the religious preferences of other students in the school; they only care about

the religious orientation of the school (see equation (5)).

Households of a given endowment type share costs equally at a private school. Thus,

the tuition equals the households’ optimal spending in education, holding their residential

locations fixed. That is, after choosing a location (d , h) with quality kdh, household n of

religious type k with income yn may send its child to a private school with tuition T and

religious orientation j = 1, 2 (Catholic or non-Catholic) that maximizes utility (1) subject to

the budget constraint (2) and the perception of school quality s = Rkj q ρ x1j− ρ , where q = y n , and

x j = T .18

The optimal tuition T determined by solving this optimal choice problem does not

depend upon Rkj, since changing Rkj only yields a monotonic transformation of the utility

function. Parents who decide to open a private school choose the school religious orientation

(Catholic or non-Catholic) for which they have a higher taste. Thus, if households of a given

endowment type with religious preferences Rk1 > Rk 2 ( Rk 2 > Rk1 ) decide to form a private

school, they will segregate themselves into a Catholic (non-Catholic) private school.19

Potentially, the model gives rise to as many private schools as households that exist in the

economy.

18

Modeling private schools as clubs is equivalent to modeling the private school market as a perfectly

competitive market where firms do not differentiate among students in their tuition policies, but do so in their

admission policies. Because of the constant returns to scale technology, all households in a given school are of the

same endowment type, and pay a tuition equal to the type’s most preferred spending in education. In equilibrium,

private schools make zero profits.

19

In particular, notice that some Catholic households may prefer non-Catholic over Catholic schools, other things

equal. The converse may also occur. In fact, almost 15% of the enrollment in Catholic schools in the United

States was accounted for by non-Catholics in 1990 (NCEA, 1990b). This might have been due not only to

preferences but also to the subsidized tuition offered by some Catholic schools, especially in inner cities. Such

subsidies can be incorporated into the model, although they have not been introduced here for computational

reasons.

13

Household Decision Problem

Households are utility-maximizing agents that choose locations (d , h) and schools

simultaneously, while taking tax rates td, district public school qualities sd, prices pdh,, and the

composition of the communities as given. Household n chooses among all locations (d , h) in

the budget set determined by the constraint (1 + t d ) p dh ≤ (1 − t y ) y n + p n . Migrating among

locations is costless in the model, and the household may choose to live in a house other than

its endowment house. For each location, the household compares its utility under public,

Catholic private, and non-Catholic private schools.

Absolute Majority Rule Voting

Households also vote on local property tax rates. At the polls, households vote for property

taxes taking their location, their choice of public or private school, property values, and the

choices of others as given when voting on local tax rates. Households that choose private

schools vote for a tax rate of zero, whereas households that choose public schools vote for a

nonnegative tax rate. Because voters choose the tax rate conditional on their school choice,

taking everything else as given, their preferences over property tax rates are single peaked, and

property tax rates are determined by majority voting. Since there is a one-to-one mapping

between property tax rates and spending per student for a given property tax base and number

of students in public schools, voting for property tax rates is equivalent to voting for school

spending.

State Funding

The state cooperates in funding public education in district d by providing an exogenous aid

amount per student, AIDd . This aid, which operates as a flat grant, is in turn funded by a state

income tax whose rate t y is set to balance the state’s budget constraint

∑ µ (N

pub

∩ J d ) AIDd = t y y (N )

d

14

(9)

where y (N ) = ∫ y n dn is the total income of all households in the state, which is equated to

N

the economy being modeled.

Equilibrium

An equilibrium in this model specifies a partition {J dh } of households into districts and

neighborhoods, local property tax rates td, a state income tax ty, house prices pdh, and a

partition of N into subsets of households whose children attend each type of school (public,

private Catholic, and private non-Catholic), such that:

(a) every house is occupied: µ ( J dh ) = µ (C dh ) ∀(d , h) ;

(b) property tax rates td are consistent with majority voting by residents who choose public

versus private school, taking their location, property values, and the choices of others as given

when voting on local tax rates;

(c) the budget balances for each district: xd = t d Pd µ (N

(d) the state budget balances:

∑ µ (N

pub

pub

∩ J d ) + AIDd ;

∩ J d ) AIDd = t y y (N ) ;

d

(e) at prices pdh, households cannot gain utility by moving and/or changing schools.

The existence of equilibrium with only public schools is proved in Nechyba (1997), and

extended to include private schools in Nechyba (1999). A similar logic can be applied to prove

the existence of equilibrium with several types of private schools. With sufficient variation in

mean neighborhood quality across districts, the equilibrium assignment of households to

locations and schools is unique (Nechyba, 1999).20

4. The Computable Version of the Model

In the computational version of the model the concept of “an economy” corresponds to a

metropolitan area. Moreover, the estimation strategy consists of simulating the equilibrium for

each metropolitan area at alternative parameter points, then choosing the point that minimizes

a well-defined distance between the equilibrium data simulated by the model and the observed

20

Due to the discreteness of housing types, there may be a range of housing prices, local property taxes, and

public school qualities associated with a given partition of households into districts, neighborhoods, and subsets

of households attending each type of school. The range decreases as the number of housing types increases.

15

data.21 Since the equilibrium cannot be solved analytically, I use an algorithm to compute it

iteratively for a tractable representation of each metropolitan area. This section describes the

setup of districts and neighborhoods in this representation, the construction of household

types, the state financial regime applied in computing the equilibrium, and the algorithm

employed.

Community Structure

In the computable version of the model there are an integer number of houses and households

in each metropolitan area, organized into districts and neighborhoods.22 I measure the size of

neighborhoods, districts, and metropolitan areas by the number of housing units.

Computational considerations prevent me from working with the actual district configuration

of each metropolitan area, splitting each district into neighborhoods of the size of

approximately a Census tract, having at least as many income levels as the ones provided by

the 1990 Census data, and including a large number of religious types.23 Thus, I aggregate the

real districts of each metropolitan area into quasi-districts in order to compute the equilibrium,

such that the largest district is a quasi-district in itself, while smaller, contiguous districts are

pooled into larger units.24 The actual 671 districts thereby yield 58 quasi-districts.25 For

illustrative purposes, Figure 1 depicts Census tracts, and school districts and quasi-districts for

the Chicago metropolitan area. Once the quasi-districts are constructed, I split them into

neighborhoods of approximately the same size, such that some districts26 have only one

neighborhood, while others have several. Larger metropolitan areas have larger

neighborhoods.

Neighborhood Quality Parameters

21

Section 6 explains the estimation strategy in detail.

Metropolitan areas are independent from one another. Each one is “an economy” in the sense of the model.

Households do not migrate across metropolitan areas.

23

The theoretical model includes K religious types, out of which L are Catholic. By a “large” number of religious

types I mean a “large” value for K, such that these K types are still split into Catholic and non-Catholic types. A

“large” number of religious types does not mean splitting K into more denominations – i.e., Catholic, Lutheran,

Baptist, Muslim, etc.

24

The size of each district is approximately a multiple of the size of the smallest district.

25

The aggregation of districts into quasi-districts produces an obvious loss of information, particularly for small,

suburban school districts.

26

From now on, “district” refers to “quasi-districts”.

22

16

In the theoretical model each neighborhood is composed of a set of homogeneous houses, such

that neighborhood h in district d has a neighborhood quality index equal to kdh. Since

neighborhood quality is not measured in standard datasets, I construct an index that captures

housing quality and neighborhood amenities, excluding public school quality.

The Census geographical concept that best approximates a neighborhood is the Census

tract. Therefore, I first compute the neighborhood quality index for each Census tract in a

metropolitan area. Then I pool tracts into neighborhoods subject to the size constraints

described above, and assign to each neighborhood the median neighborhood quality among all

the tracts that belong to the neighborhood.

To compute the neighborhood quality at the tract level, I regress the logarithm of the

tract's average rental price on a set of neighborhood characteristics and a school district fixed

effect, and then recover a metropolitan area constant.27 The neighborhood quality index for a

tract is the tract's fitted rental value, which is the sum of the "value" of the tract’s

neighborhood characteristics and a metropolitan area constant.28 The motivation for this

regression is that, roughly speaking, rental prices reflect housing characteristics, neighborhood

and metropolitan area-level amenities, and public school quality. The district fixed effect has

the purpose of netting out the school quality component from the measure of neighborhood

quality.

After obtaining the neighborhood quality index for each Census tract, I construct

neighborhoods of the desired size by pooling contiguous tracts with a similar value for the

neighborhood quality index. Finally, I assign each neighborhood the median neighborhood

quality of all the tracts belonging to that neighborhood.

For an example of the final representation of a metropolitan area through quasi-districts

and neighborhoods, see Figure 2 for the Chicago metropolitan area. The central city of

Chicago overlaps entirely with the central district. Unlike the suburban districts, which have

one neighborhood each, the central district has seven neighborhoods which differ in housing

quality. On average, the central district has the lowest housing quality in the metropolitan area.

27

The tracts located in the twenty largest metropolitan areas are used in this regression. See Ferreyra (2002) for

more details on how the neighborhood quality parameter is computed. Ideally I would use a set of variables that

reflect neighborhood physical amenities, such as quality of houses in the neighborhood, presence of parks and

open spaces, distance to major landmarks and business centers, and distance to public transportation, if

applicable. Housing quality variables are available from Census data, but the other variables have to be

constructed by the researcher. Thus, the current version employs only physical housing characteristics and

distance to the metropolitan area center.

28

Strictly speaking, the neighborhood quality index for a Census tract equals exp(fitted log of average rental

value) for that tract.

17

Household types

I consider five income levels, whose incomes are equal to the 10th, 30th, 50th, 70th and 90th

percentile of the income distribution of households with children in public or private schools

in grades 9 through 12 in a given metropolitan area.

The joint distribution of housing and income endowment is as follows. At the

beginning of the algorithm, the distribution of income in each neighborhood is initially the

same, and equal to the one that prevails for the metropolitan area as a whole. In other words,

income and housing endowments are independently distributed. In addition, religious

preferences and endowments are independently distributed.29

Recall that each household is characterized by two religious matches, one with respect

to Catholic schools and another with respect to non-Catholic schools. If household n is

Catholic, its religious preferences are described by its match with respect to Catholic schools,

RCn ,C , and its match with respect to Non-Catholic schools, RCn , NC . If household n is non-

Catholic, its religious preferences are given by its match with respect to Catholic schools,

n

n

R NC

,C , and its match with respect to non-Catholic schools, R NC , NC .

n

Since there are two types of schools, I make RCn , NC = R NC

, NC = 1 and focus on the

relative valuation of Catholic schools. Unlike income, whose distribution comes straight from

n

the data, the distribution of religious matches RCn ,C and RNC

,C needs to be estimated.

Therefore, I construct a discrete distribution of religious matches by assuming an underlying

continuous distribution. In particular, I assume that RCn ,C is distributed uniformly over the

n

interval [(1 + r )(1 − π ), (1 + r )(1 + π )] , and that R NC

,C is distributed uniformly over the interval

[(1 − r )(1 − π ), (1 − r )(1 + π )] , where

0 ≤ r < 1 and 0 < π ≤ 1 . The parameter r is both the premium

enjoyed by the average Catholic from attending a Catholic school, and the negative of the

discount suffered by the average non-Catholic from attending a Catholic school, while the

parameter π is proportional to the coefficient of variation of each distribution. Faced with the

choice between schools that are identical in everything except religious orientation, Catholics

29

For computational convenience I place ten households in each (house endowment, income) combination. For

instance, if the proportions of Catholics and Non-Catholics in the metropolitan area are 28% and 72%

respectively, then out of the ten households in each (house endowment, income) combination, I make three

Catholic and seven non-Catholic, respectively. The fraction of Catholics is the same for each endowment type,

based on the lack of empirical evidence against income and religion being independently distributed (see Ferreyra

(2002))

18

would choose non-Catholic schools if π > r /(1 + r ) , whereas non-Catholics would choose

Catholic schools if π > r /(1 − r ) .30

State Aid

Although the metropolitan areas included in my analysis fund their public schools primarily

through local sources, they still differ in the actual (and extremely complex) formulas used by

the states to allocate funds among districts.31 Therefore, I simplify the financial rules by setting

the same mechanism for all metropolitan areas – a local funding system with a state flat grant

per student, whose value equals the state aid reported by the data.

The Algorithm

In the model, the parameter vector is θ = (α , β , ρ , r, π ) . The algorithm that computes the

equilibrium for a given parameter point and metropolitan area is described in Ferreyra (2002).

Computing the equilibrium is an iterative process in which households make residential and

school choices and vote for the property taxes used to fund public schools. The process

continues until no household gains any utility by moving, switching to a different school, or

voting differently. In essence, the algorithm takes certain input, performs some operations over

it, and produces some output for a given parameter point. The input consists of the community

structure, initial distribution of household types, initial housing prices, and state aid for each

district.32 The output is the computed equilibrium, from which I extract the variables whose

predicted and observed values I wish to match.33

30

For an example on how I determine each household’s corresponding religious match, continue with the case

presented in footnote 29. Suppose that r = 0.2 and π = 0.1 . This implies that RC ,C is uniformly distributed

n

n

between 1.08 and 1.32, and RNC ,C is uniformly distributed between 0.71 and 0.88. Therefore, I assign a match

equal to 1.08, 1.2 and 1.32 to the first, second, and third Catholic household types, and a match equal to 0.72,

0.747, 0.773, 0.8, 0.827, 0.853, and 0.88 to the first through seventh non-Catholic household types. Since

religious preferences and endowment are independently distributed, the first, second, and third Catholic

household types initially placed in every (house endowment, income) combination have religious matches equal

to 1.08, 1.2, and 1.32 respectively, and a similar thing is true for the religious matches of non-Catholic

households.

31

See, for instance, Hoxby (2001).

32

Unless I state otherwise, state aid is always per student rather than the total over all students.

33

Throughout this work I assume a unique equilibrium. In future research I will explore the issue of multiple

equilibria.

19

5. The Data

I construct the distribution of income among households with children in grades 9 through 12

using data from the 1990 School District Data Book (SDDB). In addition, the state aid per

district comes from the SDDB, and the data sources used to compute the neighborhood quality

parameters are listed in Ferreyra (2002). The fraction of Catholics in a metropolitan area

comes from the 1990 Church and Church Membership in America survey. Furthermore, to

begin the algorithm I equate the initial price of all houses to the metropolitan area’s average

rental price, which I compute using the 1990 School District Data Book.

I match the observed and simulated values of the following district-level variables:

average household income, average housing rental value, spending per student in public

schools, and fraction of households with children in public schools. I calculate these variables

based on the 1990 SDDB. In addition, I would like to match the fraction of households from

each district that send their children to Catholic schools. However, the SDDB does not provide

this information; in fact, there is no data source that links households’ residence with different

types of private schools. Therefore, I am unable to match the district-level fraction of

enrollment in Catholic schools. However, I am able to match this fraction at the metropolitan

area level, and I compute the fraction of households with children enrolled in private schools

using data from the 1989 Private School Survey.

6. Estimation

I estimate the model by using a minimum distance estimator. I match the observed and

simulated values of the following district-level variables:

y1 = average household income,

y2 = average housing rental value,

y3 = spending per student in public schools,

y4 = fraction of households with children in public schools

In addition, I match y5, the fraction of households with children in Catholic schools at the

metropolitan area level. All these variables are scaled to have unit variance in the sample. Let

D denote the total number of districts in the sample (D=58), and M the number of metropolitan

20

areas (M=7). Let Nj denote the number of observations available for variable yj, j=1, …5, so

that N1= N2=N3=N4=D, and N5=M.

Assume that district i is located in metropolitan area m. Then, denote by Xi the set of

exogenous variables for district i, such that X i = xi ∪ x m ∪ x −i . Here, xi is district i’s own

exogenous data (state aid, number of neighborhoods, neighborhood quality in each

neighborhood), xm is exogenous data pertaining to metropolitan area m (10th, 30th, 50th, 70th

and 90th income percentiles, and the fraction of Catholic households in the metropolitan area),

and x −i is the “own” data from the other districts in metropolitan area m (their state aid,

number of neighborhoods, and neighborhood quality in each neighborhood). In addition, the

set of independent variables for y5m is Xm, which is the union of all the Xi sets corresponding to

the districts that belong to metropolitan area m. Finally, let ni denote the actual number of

housing units in district i, and let nm denote the actual number of housing units in metropolitan

area m.

I assume the following:

(10) E ( y ji ) = h j ( X i ,θ )

(11) E ( y 5 m ) = h5 ( X m ,θ )

j = 1,...4; i = 1,...N j

m = 1,...M

where the h's are implicit nonlinear functions. Since the yji’s are (district-level) sample means,

(12)

C ( y ji , y ki′

with V ( y ji ) =

σ jj

ni

σ jk

) = ni

0

=

σ

2

j

ni

i = i′

i ≠ i′

= σ 2ji . Similarly, given that the y5m’s are also sample means (at the

metropolitan area level), C ( y ji , y 5 m ) =

σ j5

ni

C ( y ji , y 5 m ) = 0 otherwise. Also, V ( y 5 m ) =

if district i is located in metropolitan area m, and

σ 55

nm

=

21

σ 52

nm

= σ 52m .

Estimation Strategy

Because the number of observations is rather small, I estimate the model using Feasible

Weighted Least Squares to account for heteroskedasticity across observations, and then use the

cross-equation covariances to obtain correct standard errors.34

Feasible Weighted Least Squares proceeds in two stages. The first stage determines the

value for θ that minimizes the following sum of squared residuals:35

Nj

(13) L(θ ) = ∑∑ ( y ij − yˆ ij (θ )) + ∑ ( y 5 m − yˆ 5 m (θ ) )

4

2

j =1 i =1

M

2

m =1

and the residuals from this regression are used to compute σˆ 2j and σˆ 52 . The second stage runs

Nonlinear Least Squares on variables transformed to account for heteroskedasticity, and seeks

to minimize the following sum of squared residuals in the transformed variables:

N

j

M

4

2

2

~

(14) L (θ ) = ∑∑ ( y *ji − yˆ *ji (θ )) + ∑ ( y 5*m − yˆ 5*m (θ ) )

j =1 i =1

m =1

where * denotes division by σˆ ji or σˆ 5 m . The value of θ that minimizes this function, θˆ , is

my estimate for the parameter vector.

Computational Considerations

I use a refined grid search to find the parameter estimates. In a grid search, the objective

function can be evaluated at each point independently of its evaluation at other points. This

feature allows for parallel computing, which I exploit in order to estimate the model. However,

the disadvantage of a grid search is that the size of the grid grows exponentially with the

number of parameters, which limits the number of parameters that can be estimated within a

reasonable amount of time. This explains, for instance, why my parameterization of religious

preferences is extremely parsimonious.

34

35

More details on the estimation of parameters and standard errors are provided in Ferreyra (2002).

At times I refer to the sum of squared residuals as “loss function”.

22

I use Condor to estimate the model.36 On average, this lets me evaluate the objective

function at about 250 parameter points simultaneously. Since those function evaluations are

independent of each other, Condor uses one processor for each function evaluation. A function

evaluation takes about about ten minutes on an Intel processor at an average speed of 1 Gh,

and the full two-stage procedure takes between five and six days.

Identification

The model is identified if no two distinct parameter points generate the same equilibrium for

each metropolitan area. However, the discreteness of housing and household types entails a

positive probability that a sufficiently small change in the parameters leaves the equilibrium

unchanged in each metropolitan area. This probability falls as the number of metropolitan

areas, housing, and household types grows.

Thus, identification in this model refers to

identification up to an arbitrarily small neighborhood of the true parameter point.

A sufficient condition for local identification is that the matrix of first derivatives of

the predicted variables with respect to the parameter vector has full column rank when

evaluated at the true parameter points. This requires sufficient variation in the exogenous

variables across districts and metropolitan areas. In particular, identification requires sufficient

variation in neighborhood quality and state aid across districts, in the income categories

chosen as income types within a metropolitan area, and in the fraction of Catholic adherents

across metropolitan areas. Evaluated at my parameter estimates, the matrix of first derivatives

has full column rank in my sample.

36

Condor is a project of the Computer Science Department at the University of Wisconsin-Madison

(http://www.cs.wisc.edu/condor). It is a software system that harnesses the power of a cluster of UNIX or NT

workstations on a network. Some of those workstations are specifically dedicated to highly intensive

computational jobs, and others are non-dedicated resources from offices and computer labs used by Condor

whenever they are idle. For a detailed discussion of how Condor was used to estimate the current model, see

National Center for Supercomputing Applications (2002) or http://access.ncsa/uiuc.edu/CoverStories/vouchers/

23

7. Estimation Results

In this section I analyze the parameter estimates and discuss what they imply in terms of

household and school behavior. In addition, I analyze the fit of the individual variables

matched in my estimation and discuss the limitations of these fits. Finally, I provide some

additional measures of goodness of fit.

Analyzing the parameter estimates

The parameter estimates are shown in Table 4. A simple test to determine whether the

estimates are in the right range is to compute the budget shares implied by the estimates, and

compare them with the ones implied in the data. Specifically, if housing quality were

continuous and if housing prices were proportional to housing quality, households’ optimal

choices would determine the budget shares for school spending, consumption, and housing as

follows:

(15) School spending share =

(16) Consumption share=

(17) Housing share =

α (1 − ρ )

1 − αρ

β

1 − αρ

1−α − β

1 − αρ

I use the data to compute an approximation to these shares. I calculate the school

spending share as the ratio between the average spending per student and the average

income,37 the housing share as the ratio between the average rental value and the average

income, and the consumption share as one minus the sum of the schooling share and the

housing share. This yields a schooling share of 0.13 and a housing share of 0.17, which are

reasonably close to the shares implied by the data, equal to 0.09 and 0.16 respectively.

In addition, the estimates imply that for Catholic households, RC,C is distributed

uniformly between 0.832 and 1.389, and for non-Catholic households, RNC,C is distributed

37

In this exercise I use weighted averages, with a district’s weight being equal to its size. I average over all

districts in the sample.

24

uniformly between 0.668 and 1.112. These estimates generate sufficient overlap that Catholics

may enroll in non-Catholic schools, and non-Catholics may enroll in Catholic schools.38

All the parameter estimates have very small standard errors, because my observations

are sample means computed from Census data based on thousands of observations. However,

the reported standard errors may understate the true variability to the extent that they have not

been adjusted for any of the numerical approximations employed throughout.

The model rejects the hypothesis that all moment conditions are satisfied.39 In other

words, the model fails to account for all the variation in the data,40 which is expected given the

large number of restrictions implied by the model. Furthermore, the fit of individual variables

face the limitations discussed below.

Analyzing the fit of the individual variables

Figures 3a through 3d, and figure 4 depict the predicted and observed values for each variable.

In analyzing the fit of the model, it is important to bear in mind that the aggregation and coarse

discretization imposed by computational limitations reduce the model’s ability to match the

data more closely.41

As can be seen in the figures, the model fits the district average rental value and

household income reasonably well, particularly for the large districts. The fact that the

parameter estimates capture the pattern of household sorting across jurisdictions is a promising

result, especially given the parsimonious parameterization of the model.

The model fits the district average public school spending per student less closely. This

may be due to the fact that although the metropolitan areas included in the estimation

predominantly rely on local sources for public school funding, they still differ considerably in

their financial regimes. Moreover, even districts within a state are often subject to different

38

The estimated parameters lead to the rejection of the hypothesis that the preferences of Catholics and nonCatholics for Catholic schools follow the same distribution. From the parameterization of religious preferences

presented in Section 4, it is clear that this hypothesis is equivalent to r=0, which is rejected at any standard

significance level. This provides evidence that allowing Catholics’ preferences for Catholic schools to differ from

those of non-Catholics significantly improves the fit of the data.

39

If the model is true, then the loss function evaluated at the parameter estimates follows an asymptotic chisquare distribution with degrees of freedom equal to the number of moment equations minus the number of

parameters. Since the degrees of freedom are large, the distribution of the statistic given by (loss function –

degrees of freedom)/(square root of twice the degrees of freedom), can be approximated by the standard normal

distribution.

40

Epple and Sieg (1999) report a similar result.

41

In Ferreyra (2002), I discuss these issues in detail.

25

school funding regimes.42 Yet, the funding rule used by the model ignores this heterogeneity

across districts and metropolitan areas, assumes that the state aid is exogenous with respect to

districts’ demographic conditions, and ignores the fact that when actual districts set their

property tax rates, they take into account the incentives contained in the school finance

formulas. Furthermore, the model assumes that a district’s property tax base equals the value

of residential property, and that each household that pays property taxes in a district also votes

for the property tax rate. These assumptions, however, do not hold in reality, for a district’s

property tax base usually includes non-residential property in addition to residential property,

and agents that pay property taxes on non-residential property in a district often do not

participate directly in the determination of the district’s property tax rate. While these

considerations are valid for all districts in a metropolitan area, they are particularly pertinent in

the central district, where non-residential property represents a large fraction of the total

property tax base. Since the property tax revenue is under estimated in the model and

estimation, so is the spending per student, particularly in the central districts. 43

Regarding the district-level fraction of households with children in public schools, the

fit of this variable is crucially affected by the representation of metropolitan areas and

household types. In particular, the low number of neighborhoods and households types

imposed by computational constraints implies that often all the households that choose a

particular district are relatively homogeneous, and make the same school choices. In these

cases, the district predicted fraction of households with children in public schools is either zero

or one. This feature, however, is less frequent for large districts. The limited number of

household types also affects the fit of the metropolitan area-level fraction of households with

children in Catholic schools. In particular, operating with only ten religious types seems to be

an important factor affecting the fit of this variable.44

42

For instance, all districts in the New York-Long Island metropolitan area set their own property taxes, with the

exception of the New York City School District, whose funding is provided by the government of New York City

from various sources and according to a mechanism not reflected in the model.

43

The inclusion of non-residential property in the central district does improve the fit of the district average

spending per student, but worsens the fit of other variables, most importantly the district fraction of public school

enrollment. This is because a higher spending in the central district improves the public school quality in that

district and discourages private school enrollment. In order to obtain the right level of private school enrollment,

one would need either a low productivity in public schools in the central district, or tuition subsidies for private

schools. In addition, such productivity differential or tuition subsidy should differ among districts and possibly

metropolitan areas, as suggested by some experiments I conducted. Since either possibility requires additional

parameters, they are computationally not feasible at this time.

44

For instance, 34% of the population in Philadelphia is Catholic, while 47% is Catholic in Pittsburgh. This

means that in Philadelphia, three out of ten religious types are Catholic, whereas five out of ten are Catholic in

Pittsburgh. Thus, a difference of 13% is translated into 20% of the types being different.

26

Finally, Table 5 shows the correlations between the matched variables, both for the

observed and fitted values for each version of the model. The correlations that do not involve

predicted spending per student resemble the actual correlations reasonably well.

8. Simulating Private School Vouchers

In this section I use the parameter estimates to simulate two types of voucher programs for the

Chicago metropolitan area. The first type is a universal voucher program in which every

household in the metropolitan area receives a voucher that may be used to attend any type of

private school. In the second program (“non-Catholic vouchers”), the voucher may only be

used to attend non-Catholic schools.45 In my simulations, a voucher is an amount of money

that a household receives from the state and may only be used for private school tuition.

Households may supplement the voucher with additional payments towards tuition, but cannot

retain the difference if the tuition is lower than the voucher level. Consequently, tuition is

never set below the voucher level.

Furthermore, in these simulations the voucher level is set exogenously by the state.

Vouchers are funded through a state income tax in the same manner as the state aid per

student. Thus, with vouchers, the state budget constraint (9) changes to:

(18) t y =

µ (N C ∪ N NC )v + ∑ µ (N

pub

∩ J d ) AIDd

d

y (N )

where v is the face value of the voucher. That is, the state has to fund both the flat grants given

to public school students and the vouchers given to private school students. Moreover, during

the policy simulations, household n’s budget constraint differs from the one given in (2):

(19) c + (1 +t d ) p dh + max(T − v,0 ) = (1 − t y ) y n + p n

Notice that when forming private schools, households of a given endowment level residing in

a certain neighborhood choose their optimal tuition taking into consideration the availability

45

My representation of religious preferences is not rich enough to evaluate voucher programs that prohibit the

choice of religious schools in general, so I limit the analysis to a hypothetical voucher program that prohibits only

the choice of Catholic schools.

27

and amount of vouchers. Other things equal, vouchers lead to a higher tuition (and school

quality) level while reducing the tuition share paid by parents. In addition, the definition of the

equilibrium provided in Section 3 changes under vouchers; condition (d) changes to (18), and

households maximize utility subject to the modified budget constraint (19).

The remainder of this section begins with a description of the Benchmark Equilibrium,

which is the equilibrium simulated using the parameter estimates for a non-voucher regime. It

then analyzes the outcome of a universal voucher program, and finishes with the study the

impact of a voucher program for non-Catholic private schools, and the comparison of the

effects of both voucher programs.46

Benchmark Equilibrium

The first column of Tables 6a and 6b illustrate the observed data, whereas the second column

of Tables 6a and 6b present the benchmark equilibrium. In addition, Figures 5a through 5d

contrast the observed and predicted values for some district-level variables. While the fit of the

data is obviously limited, such limitations are due to the same factors described in Section 7.

Nonetheless, the benchmark equilibrium replicates the overall pattern of income and

residential stratification observed in the data (see “Average Household Income Ratio”), with a

higher average spending per student in public schools in the districts with higher average

income and property values. Yet, the per-pupil spending in public schools is under estimated

in eight out of nine districts, likely because of the omission of non-residential property from

the property tax base (see section 7). The underestimation is proportionally larger for the

central district, whose predicted average household income and property values are so low that

the optimal voting strategy for these households in the simulated equilibrium is to vote for a

property tax rate of zero and have their public schools funded exclusively by the state (they

receive a per-student state aid of approximately $2,200).47 In addition, in the simulated

equilibrium these public schools have the lowest spending, peer quality, and overall school

quality in the entire metropolitan area.

Furthermore, in the simulated benchmark equilibrium, households that attend private

schools live in the better neighborhoods of the central district, whose tax-inclusive housing

46

The Benchmark Equilibrium is the set of initial conditions used to start the policy simulations.

According to the Financial Section of the 1990 School District Data Book. The under prediction of per-pupil

spending in the central district affects the outcomes of the voucher simulations, as will be seen later.

47

28

prices are low due to low housing and public school quality.48 The top panel of Figure 6

identifies the household types49 that choose private schools in the benchmark equilibrium.

Private school households are, on average, wealthier than public school households, but live in

houses of lower quality and property values (see Table 6b). Private school households also

have above-average taste for Catholic schools.50 On average, public schools have lower perpupil spending, peer quality and overall school quality than private schools, although with

higher variation around the mean because of their more heterogeneous student body.

In the benchmark equilibrium, Catholic schools are primarily attended by children

from Catholic households (84%) whereas public schools are mostly attended by children from

non-Catholic households. In fact, only 31% of the public school enrollment comes from

Catholic households.

Universal Vouchers

Below I analyze the effects of universal vouchers on school choices, residential decisions, and

school quality in both public and private schools. In addition, I discuss the fiscal and welfare

implications of universal voucher policies.

Household Sorting across Schools under Universal Vouchers

Table 6a presents some results from the simulation of universal vouchers for $1,000, $3,000,