Why Fight?: Examining Self-Interested Versus Communally

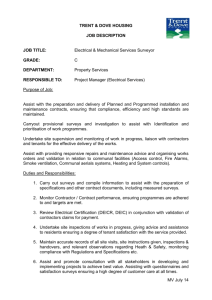

advertisement