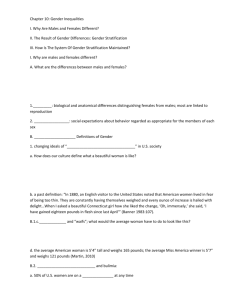

Working Group Reports

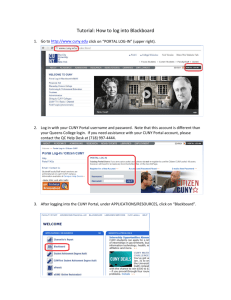

advertisement