Influence of Postmodernism on Adventist Theology

advertisement

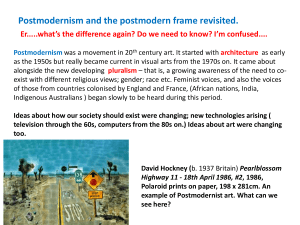

The Influence of Postmodern Philosophy and Culture On the Development of Seventh-day Adventist Theology, Education, and Mission Aleksandar S. Santrač This paper examines the nature of the postmodern influence on Adventist theology, education and mission through the prism of the two basic aspects of the postmodern worldview, i.e., its basic philosophical underpinnings and implementation of its philosophy in everyday culture and popular media. Following the attempt to define postmodernism/postmodernity and a brief presentation of its historical setting, the paper explores the three central postmodernist critiques of modernistic worldview: the critique of the absolutism of the concept of truth, the critique of reason and scientific dogmatism, and the critique of the concept of progress. Also, it discusses the two basic tenets of postmodern culture: the television and the Internet. The main objective of this paper is to propose an Adventist response to postmodernism/postmodernity, and constructive proposals for successful interaction with postmodern worldviews. This is realized through a discussion on the nature of truth, the examination of the image concept, and some practical implications for Adventist theology, education, and mission. Postmodernism (Postmodern Philosophy) One of the most comprehensive definitions of postmodern ideology is found in the Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy. It is defined as “ a complex set of reactions to modern philosophy and its presuppositions, rather than any agreement on substantive doctrines” (Audi 1995:634). As a new zeitgeist or l’esprit du siecle, postmodernism represents a post-historical reaction to modernism.1 In relation to its theoretical and philosophical classification, “ It is basically rejection of foundationalism (existence of structure of knowledge and epistemic justification), essentialism (metaphysical theory that objects have essence and appearance) and objective realism (objects exist independently of our perception and experience) (Audi 1995:634). Nevertheless, postmodernism can be more closely understood only by its historical classification. Historical Classification The term postmodernism relates rather to a time-period than to a certain ideology. It cannot signify a comprehensive worldview, since there is no “ unison of voice” among postmodernist philosophers. Therefore, one of the fundamental postulates of postmodernism is eclecticism.2 And due to its various and ambiguous theoretical forms, many view postmodernism as a threat, while others see it as the final solution to all problems of modernistic dogmatism (Dockery 1995:13). 1|Page Postmodernism, first of all, claims that human beings are unaware of the fact that a new historical era has begun. It is impossible to frantically resist the dislocation of the human condition anymore. In this context, dislocation represents a contemporary postmodernist attempt at rejecting the traditional, historical, dogmatic modernistic worldviews of Western civilization. This rejection is not a painless process. Unsurprisingly, there is a struggle against the decentralization of self.3 For almost fifty years now, we have been in the midst of the postmodern state of awareness in philosophy, sociology, literature, history, psychology, and ethics. Therefore, we have neither the freedom nor the right to deny the parousia4 of postmodernism, even in the Third World. Postmodernism rejects the premise of historical modernism. Historically, therefore, one philosophical trend is replaced by another. Michael Epstein, in his Russian Postmodernism, argues: The postmodern is the state of culture that replaces the new age and throws into the past the “modern” project, the foundations of which were the value of realistic knowledge, of individual self-awareness and rational action, and counting on the individual’s strength in the conscious self-organization of mankind. (Epstein 1999:91, italics mine) Postmodernism is not just another philosophical trend. It represents a post-historical “new age” within every aspect of human culture. In linear chronology, postmodernism is a replacement for the modern project. Slowly but surely, the modern project has been left behind. From the perspective of simplified linear chronology, all worldviews or philosophical conceptions before postmodernism can be categorized into (1) Premodernism and (2) Modernism. Premodernism encompasses the mythological worldview in which historians of philosophy usually include medieval Christianity as well. This historical trend has, as its foundation, belief in the supernatural and belief in absolute and objective truth. Whether it refers to Plato’s idealism or to Christian medieval theism, its foundation of reality was based on unquestioned, absolute revealed truth. The blend of supernatural reality and the objective approach to the truth is an apparent tenet of premodernism. There was no rational or critical evaluation of established truths. Faith was the sole path for reaching transcendent reality.5 Concerning history and dialectics, premodernism also recognized teleology within reality (Erickson 1998:15). Assuming that God created the world, the purposefulness of history is evident. The reason for existence and the final cause of the course of history is unquestionable. Therefore, according to this “doctrine,” the Absolute (God) is the source—the meaning and the aim of human existence. Premodernism emphasized traditional metaphysics and epistemology. Through faith in the supernatural (metaphysics), and the rational cognition of this world (physics and epistemology), the premodernistic intellect arrived at the truth of a God-given world. The characteristics of the modern project belong to the so-called Age of Enlightenment (“Aufklärung”), in which reason prevailed through the affluence of science and technology. One of the essential reactions to this form of modernism is the romanticism of the 19th century. The 20th century is characterized by -isms from an assortment of more recent worldviews (Marxism, fascism, positivism, existentialism, nihilism, etc.). Modernism,6 in an attempt to create a radical reaction to the premodernist premise, began to highlight complete human autonomy (emancipation of human beings), who rejected supernatural authority.7 Reason and science became the criteria of the objective view of truth. The “old gods” of premodernism were replaced by the “new gods” of reason and science. 2|Page In the modernistic age, it was believed that mankind achieved “redemption” through the active use of reason and scientific achievements. Modernism featured the negation of belief in God and the supernatural, as well as a higher criticism of Scriptures8 and other classical texts that served as the ideological foundation of the premodernistic worldview. The philosophers of the Aufklärung headed by Immanuel Kant, as well as the scientists of the new age, became the “prophets” of modernism. With a critique of premodernistic metaphysics and epistemology, they paved the way towards a new cognition of reality. The distinctiveness of premodernism and modernism could be explained by the following statement: while premodernism highlighted the dominantly irrational exclusivity and the factual plurality of “fideisms” contrasted to evidentialism (Audi 1995:253),9 modernism strove for rational monism and universalization that gave several “great stories” (meta-narrations). Postmodernism, by its chronological specification, throws modernism into history. If one adopts uniformity, the universal “love of man” and rational meta-narrations as attributes of modernism, then postmodernism represents the radical plurality or self-reliant pluralism of the often rationally ambiguous and indistinct “marginal stories.” Lyotard and Derrida are in this philosophical “camp.” On the other hand, if modernism actually represents the plurality of ideas (differentiation), then postmodernism, as a striking reaction, is based on uniformity and new universalization, or the aspiration for a unifying theory on reality. This unifying theory of postmodernism is not a fixed integrality and absolutization of truth, but a “holistic plurality” (Welsch 2000:62, 63). Examples of this contextual definition of modernism and postmodernism are the philosophical systems of Habermas and Speman. Politically speaking, the flourishing of the liberal democracy was possible on this ground. Postmodernism appeared as a remarkable historical and cultural reaction to the “shortcomings” of modernism. Lyotard reasons that “post means something like conversion: a new direction after the preceding one” (Lyotard 1995:72). This conversion consists of the final realization that reason, science, and technology cannot offer satisfactory solutions for the existential problems of mankind or promote common good. Thus, the change of historical epochs was backed up by the valid idea of linear chronology (Lyotard 1995:72). The notion depicts, in the best possible way, the chronological replacement of modernism with the post-historical epoch of postmodernism. Even though many postmodernists negate the linear concept of time and history, it is essentially impossible to deny the linear chronology of the change of cultural epochs. Moreover, it is clear to all postmodernists that the history of human thought cannot return to the premodernistic “myth” or modernistic “ratio.” Nevertheless, contemporary10 and perhaps current a-historical worldviews of postpostmodernism (digitalism or millennialism), with its machine-human behavior, which historically and conceptually go beyond the tenets of postmodernism,11 does speak about the return to performativity—new transcendence and mythical utopias of the so-called “religious fiction” of reality that ideologically relate to premodernism (Santrac 2011). Here, we are restricted only to the discussion of postmodern challenges for the Church. Following this historical classification of postmodernism, the time has come to present basic characteristics of postmodernist philosophy (a collective term for several kindred philosophies or philosophical ideologies, rather than a unified doctrine).12 3|Page A Critique of Reason, Progress and Truth Reason and the rapid development of science and technology have not led human beings to a more moral society, free of existential problems such as war, hunger, epidemic diseases, social injustice, natural disasters, and so on. Postmodernists legitimately point to the two World Wars that constituted an abominating abuse of human reason, science, and technology. Development does not mean progress at the same time, claims Lyotard (1995:73), pointing out the example of Auschwitz as the ultimate goal of the emancipation of the “modern” project of mankind.13 Therefore, postmodernists call on mankind to transcend all isms, which are inventions of the rationalistic worldview that resulted in polarization, separation, and ultimately, self-alienation and the self-destruction of humans.14 Faith in reason and progress, the postmodernists believe, should disappear from the historical-philosophical scene. One of the most meritorious precursors of the postmodernist critique of progress is Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), taken here as a case-study. In his work Antichrist, he openly claims: Mankind does not represent a development of the better or the stronger or the higher in the way that is believed today. ‘Progress’ is merely a modern idea, that is to say a false idea. The European of today is of far less value than the European of the Renaissance; onward development is not by any means, by an necessity the same thing as elevation, advance, strengthening (Nietzche 1999:1, par.4, italics mine). Nietzsche’s departure from modernistic thinking was also marked by his rejection of the concept of truth as such. In attempting to create concepts, models, paradigms, discourses about reality, we neglect the fact, Nietzsche says. He posits that reality is based on multiplicity, and that there are no two objects or two occurrences that are identical in the human experience of reality.15 Every conceptualization of reality or the creation of uniform and “great ideas about reality” 16 is an illusion. We are not called upon, Nietzsche says, to impose on reality the “explanation of meanings” when, essentially, because of the nature of reality as an uninterrupted stream of objects and events, it does not exist. Certain “laws of nature” are the illusory attempt by humans to give meaning to an inconceivable reality. Knowledge as such is an illusion. So, what is truth? “Truth” is merely the function of the human language, and it “exists” only within a specific linguistic context, Nieztsche claims: And so, what is truth? A mobile army of metaphors, metonyms, and anthropomorphisms—in short, the totality of human relations animated poetically and rhetorically, which after longlasting use appear firm, legal and obligatory for all people; truths are illusions that people do not see as such. (Nietzsche in Kaufmann 1976:46, 47) Behind this “army of metaphors” (the illusion about “the solid foundation” of the interpretation of reality), there is no meaning and sense given as the sacred aim of mankind. Thus, Nietzsche became the forerunner of a new trend in philosophical thought, whose creation of “truth” would be considered a great artistic and aesthetic game, with an unlimited scope of subjective possibilities of interpretation. And it’s not only interpretation, but in Nietzsche’s case, also the shaping of reality under the force of the desire for power. In the postmodernist world, of which Nietzsche is certainly a precursor, there is “not one word about what was once called 4|Page ‘truth’” (Nietzsche 1991:46). Truth is not something that one person has and another does not. Peasants or peasant apostles of the Lutheran kind, mostly thought about truth in that way, Nietzsche claimed. He rejected the meaning of truth as the ideal for which one should strive (Nietzsche in Kaufmann 1976:70). Therefore, “Nietzsche does not criticize false claims to truth but truth in itself and as an ideal” (Delueze 1983:95). He called for dramatization of truth (95). Such a viewpoint has become the foundation for the postmodernist understanding of truth as différence and ethical heresy (Jacques Derrida), linguistic games (Ludwig Wittgenstein), the means to attain the power of a structure that imposes a metanarrative interpretation of reality on the human race (Michel Foucault), or as the possibility of simulation (Jean Baudrillard). There is no doubt, consequently, that Nietzsche’s critique of the modernistic concept of “truth” has left an enduring influence on postmodernism. Discourse about the truth, in postmodern understanding, inevitably ends in the infinite freedom of delusions. There are other doctrinal or ethical features of postmodernist philosophy that could be evaluated here. However, this paper primarily addresses the concept of truth because it has a decisive comparative value in the dialogue about Christian/Adventist understanding of truth. Postmodernity (Postmodern Culture) Most Christians probably have some philosophical comprehension of the essence of postmodernism. However, the Church lives in a new cultural setting formed and framed by postmodern culture—Sitz im Volksleben—that can be termed as postmodernist. Postmodernity is more of a broad cultural matrix of thinking and behavior than a set of philosophical ideas and religious beliefs. John Milbank, in his article, “The Gospel of Affinity,” observes postmodernity’s loss of unified meaning or frame of existence: “Above all, postmodernity means the obliteration of boundaries, the confusion of categories. . . . Everything is made to run into everything else; everything gets blended, undone and then re-blended” (Milbank 2004:149). Television, the media, and the Internet are just some of actualities of postmodernity that have shaped our way of knowing and acting, with a special emphasis on the image as a postmodern metaphor. TV and the Media One of the most influential forms of media that appeared on the historical stage alongside postmodernism’s way of thinking was the television. Neil Postman affirmed that “television has achieved the status of meta-medium—an institution that directs our knowledge of the world and our knowledge of the ways of knowing”(Postman 1985:78-79). These new methods of knowing (unconscious epistemological frameworks) are based on postmodern criticism of reason and the thinking processes in general. Heedless of these philosophical presuppositions, millions have gone through a transformation in their way of perceiving and evaluating information. As Jacque Ellul says, “Visionary reality of connected images cannot tolerate critical discourse, explanation, duplication, or reflection. . . . Cognitive pursuits presuppose a certain distance and withdrawal from the action, whereas images require that I continually be involved in the action” (Ellul 1985:142, italics mine). There is no time for reflection any more. Image, instead of words/Word, has become the actualization of postmodern ways of knowing. The reflective thinking process left as the modern process exists no more. An image and surface reign over essence and depth of meaning. The 5|Page world has become virtual—a feature of postmodern culture that has become fully materialized in the World Wide Web. The Internet Other than through television and films, the postmodern world of virtuality is also best seen in the phenomenon of the global network of the Internet. The Internet, as a technological medium (and the popularization of reality as an image), provides the means to explore the virtual world of postmodernism. Jean Baudrillard, one of the “gurus” of postmodern vision, stresses the principle of “ navigation” through this hyper-real space. In his article, “The Author in the World of Virtual Reality,” Baudrillard (1998) explicitly refers to this technological phenomenon in the context of his philosophy of virtuality. Baudrillard attempts to criticize the phenomenon of the Internet. First, he considers that the “web” of the Internet is a modern media that certainly alienates half of the world, who will not know anything about the panoptic and peripheral space of the web (Baudrillard, 1998:1). He accuses contemporary capitalism of being the ideal creator of the Internet, in an endeavor to create the “hallucination of conquering new market spaces through the screen of the computer” (ibid.). Like television, the web has succumbed to human instincts, and entertainment is more important than knowledge, even though the majority of real knowledge is accessible only through books, Baudrillard claims.17 Does this perhaps mean that the Internet abounds with information that is only hyper-knowledge (in the sense of the simulation of knowledge)? Baudrillard’s description of the Internet is largely based on his theory of simulation. In fact, the Internet is the ultimate achievement of the creation of hyper-reality, in which there is a surplus of knowledge (hyper-knowledge) and a surplus of information (hyper-information). The Internet, this author goes on to say, is a “crude laboratory” that strips naked all human shortcomings and virtues.18 The Internet has changed life in the Western world to such an extent that the modernistic construction of highways has been replaced with the postmodernist construction of highways of information and communication. On the “mental screen” of the monitor of the computer, using Baudrillard’s language, the “death of the metaphor” is happening. What was once projected as a mental conception has now, through the Internet, become the anti-metaphorical space of absolute simulation. The Internet is becoming absolute virtuality. What should have been a “map of reality” has become reality itself. The Internet is becoming the realized world through the image on the screen. Thus, it represents the ultimate achievement of vision of imagery and virtuality. On the global network, reality is annulled and the hyper-real space of absolute simulation is created: we lose ourselves and become machines.19 Are we, then, people or machines? In the integral circuit of image reality, the answer is impossible. Moreover, the virtual is also a kind of universal synchronism: There is no present, there is no past, and there is no future, just a momentary synchronism of all places and all periods and one single, timeless virtuality. The fall or erosion of time: that is . . . what represents the fourth dimension. It is the dimension of the virtual, it is the dimension of real time; the dimension, which - far from association with others—erases all else (Baudrillard 1998:8). 6|Page In this fourth dimensional quality the life beyond time is fully attained. Disneyland heralds the end of history and time, and the beginning of the hyper-real and the virtual satellization of reality and temporality (ibid.). Man is like a mental screen in such active interferences with a machine that the subject is transformed into the object of the virtual world. The subject becomes an image of virtual reality. In this postmodernist reality, we float on the surface of the screen like phenomena, ghosts, and technological mutants. A completely different anthropology of postmodernism erases not only mental and rational abilities of human beings, but even more significantly, the moral capability to do good is undermined by the constant influence of imposed images that create hyper-reality of simulation. Everything goes, because everything is possible on the mental screen. The reality of the word (speech and understanding) has been replaced with the reality of the image. And this has great implications for the Christian understanding of reality. There are probably many more facets of postmodernity as a culture. I have opted for television and the Internet because in the context of postmodern influence on theology and the Church, they represent the “death of the Word,” in its transcendent-immanent dynamic sense, and the appearance of a pure immanent image as a new metaphor of reality. Postmodern philosophy (postmodernism) first proclaimed the “death of truth, system, and definitions,” and then, the “death of unique identity.” These developments seem to represent serious threats for Adventist Christian identity. Let us, therefore, first examine some points of postmodern ideology, with special emphasis on the nature of truth, which strongly influence Adventist theology and its educational system. Influences of Postmodernism on Adventist Theology and Education Diversity and Identity Prior to the discussion on the nature of truth within postmodern theology, “holistic pluralism” and diversity have in a postmodern context initiated in Adventist “progressive” theology, the rejection of the system itself (one of the methodological expressions of the correspondence view of truth). In this regard, the Adventist concept of the “system of truth” was indeed used historically and theologically to denote Christ, the Word of God, or the Adventist doctrinal system (White 1888:1:806; 1906:7). A crisis of systematic presentation of truth, or systematic theology and definitions, has emerged in the Adventist worldview. Bits and pieces of Adventist doctrine or biblical exegesis and spirituality are scattered, owing to the defragmentation (deconstruction?) of the “system of truth.” Without a systematic theology based on faith and reason (not only modernistic reason), there is no relevant contemporary message, and therefore, no mission of the Church. As Wolfhart Pannenberg correctly stressed: It is wrong to believe that it’s possible to jump from exegesis to preaching without systematic theological reflection. . . . [The] poor state of Christian declaration in our times calls for [a] return to systematic theology. However, if we want to seriously approach it we need extraordinary acquaintance with the horizon of philosophical problems by which systematic theological formulating of judgments is framed (Pannenberg 1996:9). 7|Page This horizon of philosophical problems is essential in formulating presuppositions for Adventist theology in general. Once we have created this ground for theology, we have “the message frame” in which we can place our theological Adventist picture. This frame consists of biblical presuppositions (the Word) vs. philosophical presuppositions (ancient and contemporary), as in other theological systems. In interpreting Christian theology, as Fernando Canale recognized, there are two types of presuppositions: hermeneutical and methodological (Canale 2001:128). Both types are significant in regard to the dialogue between the Scriptures and philosophy. Adventist identity depends on creating biblical and (not or) Christ-centered, well-adjusted systematic theology. The postmodern unsystematic approach to doctrine and religious praxis jeopardizes these efforts. Biblically speaking, diversity is praised only within the conceptual framework of God’s revelation through the Word of God. Nevertheless, what are the limits of diversity in Christian-Adventist theology we can tolerate? Let us first define tolerance in relation to the concept of truth, both in a modern and postmodern setting. Tolerance and Truth Tolerance in modernism was not factuality. Every theoretical system claiming to have absolute truth opposed the other systems of thought. All religious and ideological wars had this viewpoint in the background. Even if it could be possible to speak about the nature of tolerance in modernism, it should only be emphasized as a conscious refrain from attacking the other, but not as sacrificing the concept of the absolute for the sake of loving and accepting the other. Tolerance in postmodernism, however, views believing in absolute truth as a creation of an intolerant spiritual environment, because it is a marginalization of every other system, idea, or community. Even the quest for absolute truth has been portrayed as narrow-minded. It is understandable that this view of tolerance strived to create a peaceful and global society liberated from the evils of modernism. The holistic pluralism of liberal democracy is based on this principle. However, this mentality strongly influenced the Church, and those who believe that we are not capable of forming a legitimately unified and truthful system of beliefs basically accept this presupposition. Not to mention the fact that those who believe in absolute tolerance live in a virtual world. I believe that it is possible, after all, to believe in absolute truth and still remain tolerant and open-minded. Christ has shown the way. In front of Pilate, while confessing his identity as embodiment of absolute truth (John 18:37-38), he still succumbed to the authority of an “intolerant” Roman system (given by God). And through suffering, He became Man par excellence (John 19:5). He proved that it is possible to affirm the unconditional truth and accept the consequences for that affirmation from intolerant society. Ultimately, of course, God is the absolute Judge, and there is no eternal universal tolerance. But for the Church as his body, Christ’s demonstration shows the way of accepting absolutes while allowing people to opt for their own cherished ideas. This is, however, the way of the Cross. We should not avoid it by being tempted to choose modern or postmodern extremes. Theologia crucis is the only solution for the tension between adherence to absolute truth and absolute tolerance. Father John I. Jenkins, CSC, the President of Notre Dame University, in his commencement speech on May 2012, at Wesley Theological Seminary, brilliantly 8|Page demonstrated that we can be both confident about our own beliefs and tolerant at the same time. Mission then becomes non-judgmental persuasion in love: If I am confident in my beliefs, and I have love and good will for the other side, then it would be my duty to try to persuade them. And if I want to persuade them, then how can I vilify them? People are not persuaded by those who attack their character. But if I don’t try to persuade them, but only condemn them, then I am not showing the respect that love demands. To stand apart, proclaim my position, and refuse to talk except to judge does not reduce hatred or promote love. And if it does neither, how can it be inspired by God? (Jenkins 2012) Objective Versus Subjective Truth Postmodern theory of truth is not based only on Nietzsche’s nihilism. Truth as subjective experience and subjective faith is an established concept in Kierkegaard’s philosophy of existence. According to his philosophy, truth is subjectivity— emptied of objective and historical certainty. Truth of God or truth of salvation is highly subjective, because there are no objective measures for truthfulness (Scripture, Creeds, tradition, or Church authority) (Santrac 1999). Postmodernism has accepted this idea without critical reflection because it has the same presuppositions as existentialism, by maintaining that truth has no objective certainty. Contemporary postmodernism even claims that the talk about truth is either dogmatic or empty, and truth only serves as a simulation (a copy of the original without the original itself). The critique of objective historical truth is based on the criticism of the concept of history in general. Gary Phillips argues, “the past has no normative interpretation and no normative significance for the present” (Phillips 1995:256). In fact, for postmoderns, the historical revelation of the Bible loses its truthful and plain credibility and power of influence just because it is tied to history (an impossible objectivity in postmodern context). This idea has also impacted contemporary Catholic and evangelical hermeneutics (Santrac 2012:76, 77, 88, 153, 166). Subjective interpretation by the individual or within the framework of the community (tradition) takes precedence over objective truth in Scripture, known through a plain reading in the Spirit. The Adventist historical and objective metanarrative (the Great Controversy system of truth) has been under threat by this postmodern idea. Objective doctrinal truth (rejected by Christian existentialism and consequently postmodernism) is also under attack in Church intellectual circles. The spirituality vs. doctrine model is based on the subjective vs. objective truth concept. Certainly, this objectivity of truth is not devoid of personal appropriation of philosophia perrenis. Eternal values and principles (unconditionally revealed by God) are accepted by faith as personal and conditional assent to the truth. This is biblical subjectivity of truth that we should explore further. Reason and Intuition The postmodern generation of anti-rational comprehension of the world has been influencing the Adventist spiritual environment. Postmodern intuition, or even radical silence, has impacted the epistemological and ethical religious framework that replaced reason and intelligent reflection. Personal intuitive religion cannot play any role in shaping Adventist doctrine and spirituality. Reason is public, not private. “Religion is private; reason, on the 9|Page contrary, is public. Only a natural religion that satisfies the critical principles of reason is worthy of a place in the public sphere” (Dalferth 2000:8). Accordingly, the concept of rationality emphasizes neutrality, universality, and publicity (“rational” is only what allows itself to be presented before the critical eyes and ears of all).20 One cannot accomplish this through intuition. The doctrines of the church are rational. The second reason is based on the biblical understanding of mind and thought. It has to do with rationality of faith. According to Frank Hasel, “Faithful reason is not a sacrifice of the intellect, but the integration of reason into faith” (Hasel 1993:185). Consequently, the primacy of faith is stressed, with reason following. Nevertheless, the mind is still necessary in complete apprehension of God’s truth. Also, human beings must not become a mental screen. We are primarily Homo sapiens, not just Homo videns. The vision (image) of the postmodern world, with the superficiality of the disinterested and dispassionate mind, should not erase the necessity of reasoning and debating in a religious sphere. The image (εἰκών) must not push reason (λόγος) (word, speech, thought) into oblivion. Finally, in this debate over the nature of truth and reason, I would like to make just a few remarks about the false dichotomy between theology and practice. The disconnection of lifestyle with the theology of the church appeared in our midst parallel with the emergence of postmodernity. Doctrine has been pushed aside in order to establish a so called practical relevance of the truth. Lifestyle, consequently, is being formed by this wrong and unbiblical idea. Miroslav Volf from Yale undoubtedly affirms the close relationship between theological science (theory) and Christian practice. He says, “At the heart of every good theology lies not simply a plausible intellectual vision but more importantly a compelling account of a way of life, and that theology is therefore best done from within the pursuit of this way of life” (2002:247). This sounds postmodern, but Volf still assumes that intellectual vision is a considerable substance of sound theology. The practical relevance of Adventist doctrine for the Adventist way of life is, of course, essential. Speaking about praxis without the importance of the teachings of the Church and its interpretation is like speaking about the importance of the branches of the tree without its roots. Branches can be beautiful and very attractive, but if they are not supported by the life-giving root, they will become dry. Christ is the truth, appropriated by faith and reason, and demonstrated in everyday spiritual lifestyle or way of life. There is no dichotomy between sacra doctrina and vita contemplativa/activa. Let us now examine the basic tenets of postmodern culture which form a new Adventist identity. This will be done briefly and concisely, with special emphasis on image metaphor. Challenges and Opportunities of Postmodernity in the Adventist Liturgy and Mission Word and Image The image has become a token of postmodernity. The valueless reality of the image has replaced the depth of the Word (written) and Speech (proclamation). And, Adventist praxis has apparently been influenced by this transformation. The image mentality, deeply grounded in the mind of those who have allowed themselves to be under the influence of the postmodern lifestyle can be noticed in the understanding and practice of worship, new spirituality, and way of life. 10 | P a g e In order not to misplace the importance of the written Word, new possible ways need to be presented. One needs to avoid the image-reflecting religious activity only as intrinsically deceptive both in theology and worship. However, in postmodernity, it is almost impossible to avoid the prominence of the image-making reality. Is there a hope therefore, for finding middle ground? Michael J. Glodo, an evangelical scholar, offers the possibility of the Bible Stereo presentation of the truth. Christ (as Word (λόγος) and Image (εἰκών)), Worship (as consisting of the Word and Image (Rites)), and ethics (as combined dialog of the Word and Community Life (Image)) are the Christian realities that could be understood only in this stereo mode (Glodo 1995:148-172). This hermeneutics of imagination vs. postmodern hermeneutics of suspicion and suspension of the Word, accepted as biblical, and at the same time contextual in a postmodern age of virtuality, must never neglect the importance of the cognitive understanding of the Word. Christ indeed is the εἰκών. The New Living Translation (2007) expresses Col 1:8 as “Christ is the visible image of the invisible God. He existed before anything was created and is supreme over all creation.” This Christological concept plays a pivotal role in dialog with postmodern theology. Nevertheless, Image-Word stereo theology is a balanced representation of the Church’s doctrine and life for the purpose of communication with postmodern philosophy. Thus, Christ as an Image might become both the challenge (idolatry of postmodern metaphor) and the opportunity (presentation of truth to postmoderns in postmodern terms). The difference is determined by the proper understanding of the Word in Scripture and the appropriate liturgical experience in the Holy Spirit. The Image of an idolatrous Jesus of culture is contrasted with the Image of the biblical Christ of faith. Worship and music, furthermore (very often devoid of ethical value and doctrinal importance of truth), represent the grounds for the adoption of the so-called emotivism. Emotivism is the basic ideological background of the new postmodern esthetic performance in religion (or performatism in post-postmodernism). The lack of rational, intelligent, and sacrificial submissiveness to God’s revelation, and adherence to the objective ethical principles of community based on the law of God, can lead to a liturgical experience resulting in a completely oblivious and insensible conscience. Image without the Word is void. The Word without Image is, of course, equally empty. Mission in a Postmodern Context The uniqueness of Adventist mission under the influence of the postmodern concept of subjective/irrational concept of truth, and postmodernity’s understanding of reality as an image have been almost erased. There are at least three additional reasons for this. First, fear of betraying the idea of the global community and tolerance of liberal democracy. Second, a stronger emphasis on cultural uniqueness or Fritz Guy’s localization of Adventist experience of faith (Guy 1999:234-235). Third, a lack of missionary zeal due to the influence of an incorrect theology of Christian identity offered by non-Adventists, and the impact of rejection of the biblical idea of election of the community (remnant). We could elaborate on each of these reasons and discuss their clarity or/and disputability. The postmodern spiritual environment has almost succeeded in erasing remnant awareness crucial for Adventist mission, distinctiveness, and global orientation. Currently, when the substantial part of the prophetic insight of the 19th century understanding of Scripture is being fulfilled, it is essential to recognize the importance of remnant identity, and the urgency of the 11 | P a g e proclamation of present truth (system of truth). In spite of the fear of global forces, cultural micro-narrative differences, other challenges (ordination of women), and possible crisis of an “assertive” missionary effort due to the debate on proselytism, the biblical truth of the remnant stands unchangeable and perpetual, because it is the truth of the living God. Conclusion As a possible transcending solution for both ideological (truth!) and practical (image!) influences of the postmodern way of thinking and culture on Adventism, I propose the following seven reminders for the Adventist mission in 21st century (postmodern or post-postmodern): 1. The preeminence of the Word of God (truth as historical revelation, rational, and objective) must be stressed again. In teaching (education) and preaching (proclamation), the Scriptures play a pivotal role in framing our theological thinking and lifestyle. 2. Adventist exclusiveness in theology has to be defined, and only then defended. The foundations (theological and philosophical presuppositions) of Adventism need further intelligent exposition. The significance of present truth (Rev 14) and the identity of the distinct and unique movement with a global mission need to be established and discussed further. 3. Peculiarity in lifestyle needs to be lived unashamedly, but in a non-legalistic, nonjudgmental, and loving way because postmoderns search for transformative integrity. 4. Submissiveness to the tradition of the community of faith (accepting ethical standards of an Adventist identity) needs to be emphasized more. Ethical standards constitute a progressive extrapolation of the interpretation of Scripture, of course, but they also represent the indispensable rule of faith. 5. Tolerance as a way of the Cross (to live by the objective truth of Scripture and still be inclusive, forbearing, and open-minded, i.e., Christ-like longsuffering) is biblical. God is the ultimate objective truth who judges our subjectivity. In Christ, however, we have the tolerant objectivity of truth. 6. Connection between the doctrine of the church and lifestyle and worship (Word and Image) has to be further developed. λόγος and εἰκών are both essential for the successful mission in the 21st century. 7. The power of God in Christ (spiritual and transformative) has to be proclaimed and lived, because the concept of power has become a new post-postmodern metaphor (and a point of reference) in a spiritual age of powers and supernatural forces (Santrac 2011:9-10). Above all, spiritual progress and new revival and reformation of the Adventist Church depends upon the acceptance of basic and plain truths of Scripture understood and proclaimed by the Spirit in the community of faith. Our identity, mission, and ultimate survival depends on refraining from all theological, spiritual, and liturgical extremes, which deviate from Christ-like faith and experience, as well as authenticity and integrity. Ellen White wrote, “The progress or reform depends upon a clear recognition of fundamental truth. While, on the one hand danger lurks in a narrow philosophy and a hard, cold orthodoxy, on the other hand there is a great danger in a careless liberalism. The foundation of all enduring reform is the law of God (White, 1905:129, italics mine). Between the cold orthodoxy of modern Adventism and a careless liberalism of (post!) postmodern Adventism are erected the pillars of faith “which was once for all delivered to the saints” (Jude 3, NKJV). Aleksandr Solzhenitsyin once said: “The simple step of a courageous individual is not to take part in the lie. One word of truth outweighs the world” (Solzhenitsyin 12 | P a g e 2012). Are we courageous enough to bring yet again Christ’s one and symmetric Word of truth to the contemporary world? Works Cited Audi, Robert. 1995. Postmodern. Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy, ed. Robert Audi. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ________. 1995. Evidentialism. Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy, ed. Robert Audi. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Baudrillard. Jean. 1998. Pisac u svetu prividne stvarnosti (The Writer in the World of Virtual Reality). Književnost 1-2:389-391. Canale, Fernando. 2001. Understanding Revelation-Inspiration in a Postmodern World. Berrien Springs, MI: Andrews University. Dalferth, Ingolf U. 2000. I determine What God Is! Theology in the Age of “Cafeteria Religion.” Theology Today 57 (April). P. 5-23. Delueze, Gilles. 1983. Nietzsche and Philosophy. New York:The Athlone Press. Dockery, David. 1995. The Challenge of Postmodernism. The Challenge of Postmodernism, ed. David S. Dockery, p. 13-18. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books. Ellul, Jacque Ellul. 1985. The Humiliation of the Word, Trans. Joyce Main Hanks. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans. Epstein, Michael. 1999. Russian Postmodernism: New Perspectives on Post-Soviet Culture. Oxford, New York: Berghahn Books. Erickson, Millard. 1998. Postmodernising the Faith: Evangelical Response to the Challenge of Postmodernism. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books. Glodo Michael J. 1995. New Opportunities for Biblical Interpretation in an A-Rational Age. In The Challenge of Postmodernism: An Evangelical Engagement, ed. David S. Dockery, 148-172. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books. Guy, Fritz. 1999. Thinking Theologically: Adventist Christianity and the Interpretation of Faith. Berrien Springs, MI: Andrews University Press. Hasel, Frank. 1993. Theology and the Role of Reason. JATS 4, no. 2 (Autumn):172-198. Jenkins, John I. 2012. Wesley Theological Seminary Commencement in the National Cathedral (May 7). http://president.nd.edu/communications/wesley-theological-seminarycommencement (accessed 5 September 2012). Kaufmann, Walter, Ed. 1976. The Portable Nietzche. New York: Penguin Books. Lyotard, Jean Francois. 1995. Šta je postmoderna (What Is Postmodern) Belgrade, Serbia: Art Press. Milbank, John. 2004. The Gospel of Affinity. In The Future of Hope: Christian Tradition Amid Modernity and Postmodernity, eds. Miroslav Volf and William Katerberg, p. 149-169. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans. Nietzsche, Friedrich. 1999. Antichrist. Trans. L. H. Mencken. Tucson, AZ: Sharp Press. Okosun, T. Y. 2012. The Problem of the Social Self in the Post Postmodern Scene. http://www.neiu.edu/~tokosun/Courses/postmodern1.htm (accessed 5 September 2012). Pannenberg, Wolfhart. 1996. Theologie und Philosophie. Gottingen, Germany: Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht. Phillips, Gary. 1995. Religious Pluralism in a Postmodern World. In The Challenge of Postmodernism, ed. David S. Dockery, p. 244-266. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books. Postman, Neil Postman. 1985. Amusing Ourselves to Death. New York: Penguin. 13 | P a g e Santrac, Aleksandar S. 1999. Biblical Evaluation of Soren Kierkegaard’s Concept of Truth as Subjectivity. MA Thesis. Andrews University, Berrien Springs, MI. ________. 2011. Beyond Postmodernism: Are We Aware of the New Worldview. http://www.aleksandarsantrac.info/docs/Unpublished/Beyond%20Postmodernism.pdf (accessed 5 September 2012). ________. 2012. Sola Scriptura: Benedict XVI’s Theology of the Word of God. PhD dissertation. North-West University, Potchefstroom, Republic of South Africa. Schmidt, Burghard. 1995. Protivurečnosti postmoderne (Controversies of the Postmodern). Beograd, Serbia: Art Press. Solzhenitsyn, Aleksandr I. 2012. Quotes. http://www.goodreads.com/author/quotes/10420.Aleksandr_I_Solzhenitsyn (accessed 6 September 2012). Volf, Miroslav. 2002. Theology for a Way of Life. In Practicing Theology: Beliefs and Practices in Christian Life, ed. Miroslav Volf and Dorothy C. Bass, 245-263. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans. Wallace, Stan. 2012. Discerning and Defining Postmodernism http://www.leaderu.com/real/ri9802/wallace.html (accessed 5 September 2012). Welsch, Wolfgang. 2000. Naša postmoderna moderna (Our Postmodern Modern), Novi Sad, Serbia: Publishing and Book Store of Zoran Stojanović. White, Ellen. 1888. Materials, 4 vols. Hagerstown, MD: Review and Herald. ________. 1905. The Ministry of Healing. Mountain View, CA: Pacific Press. ________. 1906. How to Study the Bible. Signs of Times, (September 19). http://text.egwwritings.org/publication.php?pubtype=Periodical&bookCode=ST&lang=e n&year=1906&month=September&day=19 (accessed 7 November 2012). Endnotes 1 It is a palette of varying philosophic, sociological, hermeneutic, historical, anthropological, ethical… ideas, which surpass everything that has been a part of the traditional (modern) history of philosophy, sociology, hermeneutics, history, anthropology, and ethics. 2 Within the conceptual framework of postmodern philosophy one can find the deconstructive (philosophical and linguistic), liberational (social and political), constructive (with emphasis on a new worldview), restorational or conservative (with emphasis on the good sides of premodernism and modernism) postmodernism, etc. 3 Or the decentralization of the ego (a favourite term of Foucault and other postmodernists). 4 The Greek term parousia means both "arrival" and "presence". 5 Of course, fides quaerens intellectum. 6 Certain historians believe that modernism spanned the historical period from the French bourgeois revolution in 1789 until the fall of the Berlin wall in 1989. 7 On these grounds Erickson based the ten characteristics of modernism: 1. naturalism; 2. humanism; 3. scientific method; 4. reductionism (reducing the man to a higher form of machine or animal); 5. progress; 6. nature as the highest authority; 7. certainty of objective knowledge; 8. determinism; 9. individualism and 10. anti-authoritarianism (Erickson, 1998: 16-17). 14 | P a g e 8 The criticism of biblical scripts or biblical criticism was an attempt to relieve the biblical revelation of "mythical sediment" and create a historic extract, free of the supernatural. In the XX century, this process also became known as demythologization (Rudolph Bultmann). 9 Fideism is the claim that one’s fundamental religious convictions are not subject to independent rational assesment (See Audi, 1995:266). 10 Proposed date of the commencement of post-postmodernism is September 11, 2001 (Fall of World Trade Center Twin Towers). 11 Okosun observes: “…post-postmodernism is the result of the intellectual and social ahistoricity of the West concentrated especially in the United States. Despite the intensity of ahistoricity, there are still a large number of people in pre-modernity who respect history and tradition. It is hard to conceive that advancement or being developed are synonymous to not speaking to each other, litigating at every excuse, and smearing each other with excreta. The result of our machine behavior is of course the enthronement of one huge putrid social scene from which there seems now to be no escape. The other point is that many people in the West, especially the United States, will insist that this is not the case, and that although everything may not be well, we still enjoy some sense of well-being and tranquility. That is precisely the postpostmodern scenario” (Okosun, 2012). 12 The following article is a useful, brief presentation of the basic precepts of postmodernism: see Wallace, 2012. 13 The essence of the criticism of modernity lies in the criticism of the idea of progress. Quoting Benjamin, Schmidt says: "The notion about mankind's progress through history cannot be separated from the notion of its continuity, passing through homogenous and empty time. Criticism of the notion about this continuity must in general create a foundation for the criticism of the notion of progress" (Schmidt, 1995: 34). 14 The polarisation and separation of mankind is embodied in the rapid increase of the intensity of racism, fascism, anti-semitism, etc. in the XX century, which represents the end of modernism. 15 As an example of this notion of reality, Nietzche cites the concept or idea of "a leaf". Although all leaves share certain characteristics, no two leaves are the same. When we form the notion of "a leaf" in our mind, we thus take something away from the nature of reality, which is basically chaos that opposes organisation through conception (Kaufmann, 1976: 46). 16 This idea largely reminds one of the postmodernist criticism of the metadiscourse or great narration about reality and history, which are especially noticeable in the work The Postmodern State by Jean-Francois Lyotard. 17 Besides having openly criticized the Internet, Baudrillard has also criticized computers and mobile phones as “tools that tend to put the individual into a completely closed universe, to make him an operational monade” (Baudrillard, 1998:8). 18 "The Internet is a raw laboratory in which the flaws and virtues of mankind are expressed in the nakedness of our fundamental inadequacies. All paragons of human frailty remain here: dissolution of wisdom, information, rumours, hints, gossip, small talk, debates, indolent mutuality, deliberate twisting of truth, disfigurement, self-deception, banality of info-prattling…" (Baudrillard, 1998:8). 19 Man's alienation from man is a thing of the past; man becomes "sunk" in the homeostasis of machines. 20 Ibid., 9. 15 | P a g e