Defining Postmodernism: Art, Architecture, and Culture

advertisement

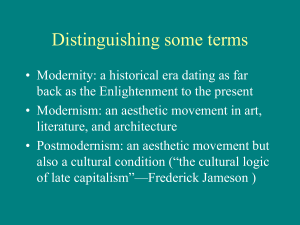

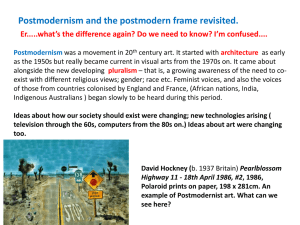

Defining Postmodernism In the interest of providing some sense of the range of the debate surrounding postmodernism, a debate which is central to much current thinking on hypertext, here is a definition provided by James Morley. It appears here as it was posted on the Postmodern Culture electronic conference list. What is postmodernism? Firstly, postmodernism was a movement in architecture that rejected the modernist, avant garde, passion for the new. Modernism is here understood in art and architecture as the project of rejecting tradition in favour of going "where no man has gone before" or better: to create forms for no other purpose than novelty. Modernism was an exploration of possibilities and a perpetual search for uniqueness and its cognate--individuality. Modernism's valorization of the new was rejected by architectural postmodernism in the 50's and 60's for conservative reasons. They wanted to maintain elements of modern utility while returning to the reassuring classical forms of the past. The result of this was an ironic brick-a-brack or collage approach to construction that combines several traditional styles into one structure. As collage, meaning is found in combinations of already created patterns. Following this, the modern romantic image of the lone creative artist was abandoned for the playful technician (perhaps computer hacker) who could retrieve and recombine creations from the past-data alone becomes necessary. This synthetic approach has been taken up, in a politically radical way, by the visual, musical,and literary arts where collage is used to startle viewers into reflection upon the meaning of reproduction. Here, pop-art reflects culture (American). Let me give you the example of Californian culture where the person--though ethnically European, African, Asian, or Hispanic--searches for authentic or "rooted" religious experience by dabbling in a variety of religious traditions. The foundation of authenticity has been overturned as the relativism of collage has set in. We see a pattern in the arts and everyday spiritual life away from universal standards into an atmosphere of multidimentionality and complexity, and most importantly--the dissolving of distinctions. In sum, we could simplistically outline this movement in historical terms: 1. premodernism: Original meaning is possessed by authority (for example, the Catholic Church). The individual is dominated by tradition. 2. modernism: The enlightenment-humanist rejection of tradition and authority in favour of reason and natural science. This is founded upon the assumption of the autonomous individual as the sole source of meaning and truth--the Cartesian cogito. Progress and novelty are valorized within a linear conception of history--a history of a "real" world that becomes increasingly real or objectified. One could view this as a Protestant mode of consciousness. 3. postmodernism: A rejection of the sovereign autonomous individual with an emphasis upon anarchic collective, anonymous experience. Collage, diversity, the mystically unrepresentable, Dionysian passion are the foci of attention. Most importantly we see the dissolution of distinctions, the merging of subject and object, self and other. This is a sarcastic playful parody of western modernity and the "John Wayne" individual and a radical, anarchist rejection of all attempts to define, reify or re-present the human subject. Ask an Expert: What is the Difference Between Modern and Postmodern Art? A curator from the Hirshhorn Museum explains how art historians define the two classifications By Megan Gambino SMITHSONIANMAG.COM SEPTEMBER 23, 2011 All trends become clearer with time. Looking at art even 15 years out, “you can see the patterns a little better,” says Melissa Ho, assistant curator at the Hirshhorn Museum. “There are larger, deeper trends that have to do with how we are living in the world and how we are experiencing it.” So what exactly is modern art? The question, she says, is less answerable than endlessly discussable. Technically, says Ho, modern art is “the cultural expression of the historical moment of modernity.” But how to unpack that statement is contested. One way of defining modern art, or anything really, is describing what it is not. Traditional academic painting and sculpture dominated the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries. “It was about perfect, seamless technique and using that perfect, seamless technique to execute very well-established subject matter,” says Ho. There was a hierarchy of genres, from history paintings to portraiture to still lifes and landscapes, and very strict notions of beauty. “Part of the triumph of modernism is overturning academic values,” she says. In somewhat of a backlash to traditional academic art, modern art is about personal expression. Though it was not always the case historically, explains Ho, “now, it seems almost natural that the way you think of works of art are as an expression of an individual vision.” Modernism spans a huge variety of artists and kinds of art. But the values behind the pieces are much the same. “With modern art, there is this new emphasis put on the value of being original and doing something innovative,” says Ho. Edouard Manet and the Impressionists were considered modern, in part, because they were depicting scenes of modern life. The Industrial Revolution brought droves of people to the cities, and new forms of leisure sprung up in urban life. Inside the Hirshhorn’s galleries, Ho points out Thomas Hart Benton’s People of Chilmark, a painting of a mass of tangled men and women, slightly reminiscent of a classical Michelangelo or Théodore Géricault’s famous Raft of the Medusa, except that it is a contemporary beach scene, inspired by the Massachusetts town where Benton summered. Ringside Seats, a painting of a boxing match by George Bellows, hangs nearby, as do three paintings by Edward Hopper, one titled First Row Orchestra of theatergoers waiting for the curtains to be drawn. In Renaissance art, a high premium was put on imitating nature. “Then, once that was chipped away at, abstraction is allowed to flourish,” says Ho. Works like Benton’s and Hopper’s are a combination of observation and invention. Cubists, in the early 1900s, started playing with space and shape in a way that warped the traditional pictorial view. Art historians often use the word “autonomous” to describe modern art. “The vernacular would be ‘art for art’s sake,’” explains Ho. “It doesn’t have to exist for any kind of utility value other than its own existential reason for being.” So, assessing modern art is a different beast. Rather than asking, as one might with a history painting, about narrative—Who is the main character? And what is the action?—assessing a painting, say, by Piet Mondrian, becomes more about composition. “It is about the compositional tension,” says Ho, “the formal balance between color and line and volume on one hand, but also just the extreme purity of and rigor of it.” According to Ho, some say that modernism reaches its peak with Abstract Expressionism in America during the World War II era. Each artist of the movement tried to express his individual genius and style, particularly through touch. “So you get Jackson Pollock with his dripping and throwing paint,” says Ho. “You get Mark Rothko with his very luminous, thinly painted fields of color.” And, unlike the invisible brushwork in heavily glazed academic paintings, the strokes in paintings by Willem de Kooning are loose and sometimes thick. “You really can feel how it was made,” says Ho. Shortly after World War II, however, the ideas driving art again began to change. Postmodernism pulls away from the modern focus on originality, and the work is deliberately impersonal. “You see a lot of work that uses mechanical or quasi-mechanical means or deskilled means,” says Ho. Andy Warhol, for example, uses silk screen, in essence removing his direct touch, and chooses subjects that play off of the idea of mass production. While modern artists such as Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman made color choices that were meant to connect with the viewer emotionally, postmodern artists like Robert Rauschenberg introduce chance to the process. Rauschenburg, says Ho, was known to buy paint in unmarked cans at the hardware store. “Postmodernism is associated with the deconstruction of the idea, ‘I am the artistic genius, and you need me,’ ” says Ho. Artists such as Sol LeWitt and Lawrence Weiner, with works in the Hirshhorn, shirk authorship even more. Weiner’s piece titled “A RUBBER BALL THROWN ON THE SEA, Cat. No. 146,” for example, is displayed at the museum in large, blue, sans-serif lettering. But Weiner was open to the seven words being reproduced in any color, size or font. “We could have taken a marker and written it on the wall,” says Ho. In other words, Weiner considered his role as artist to be more about conception than production. Likewise, some of LeWitt’s drawings from the late 1960s are basically drawings by instruction. He provides instructions but anyone, in theory, can execute them. “In this post-war generation, there is this trend, in a way, toward democratizing art,” says Ho. “Like the Sol LeWitt drawing, it is this opinion that anybody can make art.” Labels like “modern” and “postmodern,” and trying to pinpoint start and end dates for each period, sometimes irk art historians and curators. “I have heard all kinds of theories,” says Ho. “I think the truth is that modernity didn’t happen at a particular date. It was this gradual transformation that happened over a couple hundred of years.” Of course, the two times that, for practical reasons, dates need to be set are when teaching art history courses and organizing museums. In Ho’s experience, modern art typically starts around the 1860s, while the postmodern period takes root at the end of the 1950s. The term “contemporary” is not attached to a historical period, as are modern and postmodern, but instead simply describes art “of our moment.” At this point, though, work dating back to about 1970 is often considered contemporary. The inevitable problem with this is that it makes for an everexpanding body of contemporary work for which professors and curators are responsible. “You just have to keep an eye on how these things are going,” advises Ho. “I think they are going to get redefined.” Read more: http://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/ask-anexpert-what-is-the-difference-between-modern-and-postmodernart-87883230/#P1uiG4gWHE2V7uU0.99 Give the gift of Smithsonian magazine for only $12! http://bit.ly/1cGUiGv Follow us: @SmithsonianMag on Twitter