Chapter 4 - Marine Plants

advertisement

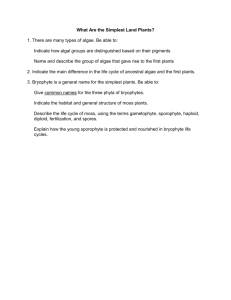

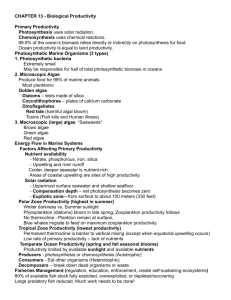

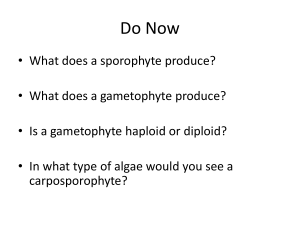

Chapter 4 - Marine Plants Chapter Summary Anthophytes are flowering plants with a dominant sporophyte generation and a reduced gametophyte generation. Unlike on land, anthophytes are not the dominant macroscopic plants in the ocean, but they do have marine representatives that are primarily found near the coast, such as seagrasses, marsh grasses, and mangals. All types of marine flowering plants host a unique community of organisms within the habitat they create. Multicellular algae, otherwise termed “seaweeds,” dominate in the marine environment, especially brown and red algae. There are three major divisions of algae: the green Chlorophyta, the brown Phaeophyta, and the red Rhodophyta. Other than morphological features, accessory pigments are a characteristic used to categorize the algae. Accessory pigments are functionally and physiologically very important. These pigments capture light of a variety of wavelengths other than those captured by the primary photosynthetic pigment, chlorophyll a. With the evolution of accessory pigments, algae have been able to occupy habitats of various depths that otherwise would have been uninhabitable. Most algae have common morphological features that can be readily identified. The holdfast is a structure that anchors the plant to the substrate, the stipe is the "trunk" of the plant that enables it to grow towards the surface, and the blades contain the photosynthetic tissues and are generally oriented towards the lighted areas of the region. Other structures, such as gas-filled pneumatocysts, are present on some species. These structures act as floats that bring the blades to lighted surface waters. Reproduction in multicellular algae differs from that of flowering plants. As is common with all plants, algae undergo alternation of a sporophyte and gametophyte generation and, in general, the gametophyte generation is dominant with a reduced sporophyte. There are, however, many variations in terms of alternation of generations for algae and each species needs to be considered individually. As introduced in chapter 3, nutrients, especially nitrogen and phosphorus, and sunlight are necessary for growth and reproduction of phytoplankton. Spatial and temporal variations in available sunlight, nutrients, and grazers cause significant seasonal and global differences in marine production. Thus, in many regions of the ocean, these necessities can be limited to a point where they prohibit population growth. Nutrient amounts and distribution are determined by physical phenomena. In upwelling regions, nutrient-poor surface waters are continually replaced by deeper nutrient-rich waters and large ecosystems are supported, such as the anchoveta ecosystem off the Peruvian coast. In tropical regions, upwelled nutrients are blocked by a persistent thermocline and surface waters exhibit low rates of production and year-round plankton communities that resemble those of temperate regions during summer months. Tropical coral-reef ecosystems rely on the symbiotic relationship between corals and zooxanthellae rather than conventional phytoplankton photosynthesis (see chapter 9 for details). We have to consider influences of local phenomena as well as global phenomena to get a sense of global primary productivity because primary productivity can vary locally. In general, spatial variations in primary production are common, with mid- and high-latitude regions, shallow coastal areas, and upwelling zones being the most prolific, but only during warm summer months when sufficient sunlight is available.