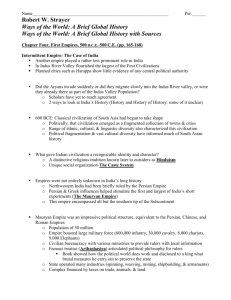

Big Era Two - World History for Us All

advertisement