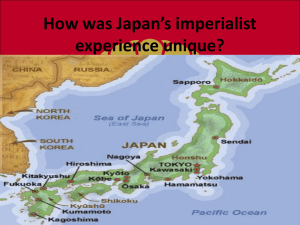

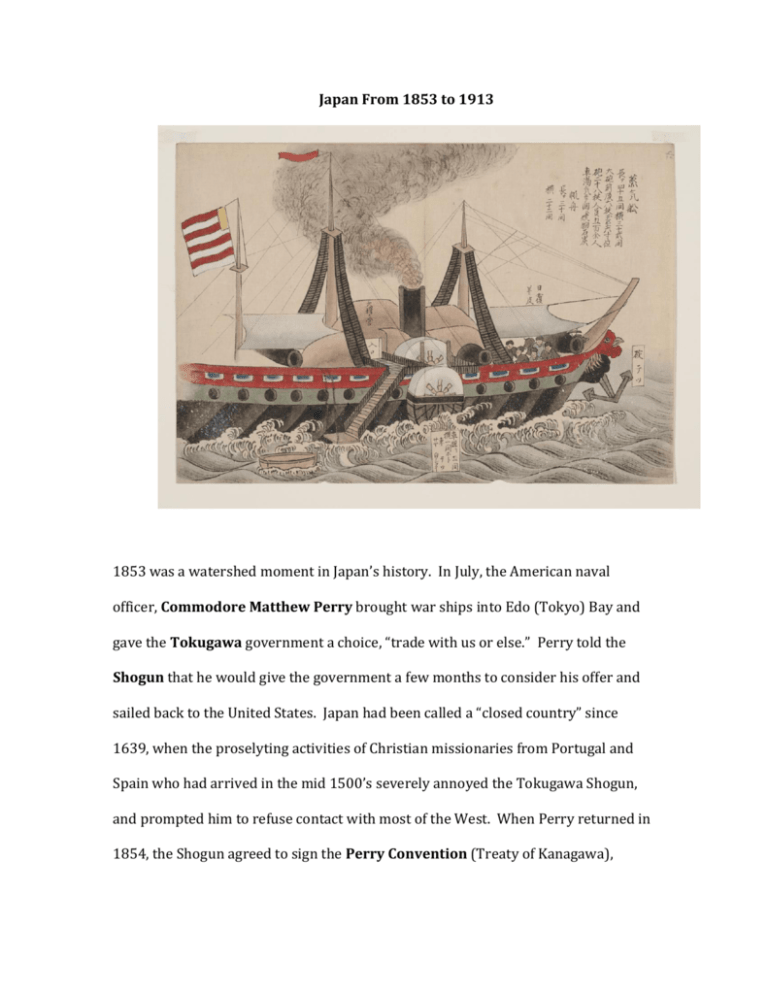

Japan From 1853 to 1913 1853 was a watershed moment in Japan's

advertisement

Japan From 1853 to 1913 1853 was a watershed moment in Japan’s history. In July, the American naval officer, Commodore Matthew Perry brought war ships into Edo (Tokyo) Bay and gave the Tokugawa government a choice, “trade with us or else.” Perry told the Shogun that he would give the government a few months to consider his offer and sailed back to the United States. Japan had been called a “closed country” since 1639, when the proselyting activities of Christian missionaries from Portugal and Spain who had arrived in the mid 1500’s severely annoyed the Tokugawa Shogun, and prompted him to refuse contact with most of the West. When Perry returned in 1854, the Shogun agreed to sign the Perry Convention (Treaty of Kanagawa), which opened two ports to American trade and allowed for a United States consul and extraterritoriality for Americans in Japan. Perry’s arrival created a crisis for the already weakened Tokugawa government. In Japan’s two hundred years of self-imposed isolation, the country had not developed beyond the feudal age (the Tokugawa was a military government in which order was kept by sword-wielding samurai) so the modern American warships that Perry brought signaled to the Japanese that they needed to develop new technology—and fast. A significant element of the government felt that the Shogun had grossly mishandled the Perry situation and they moved to overthrow the Tokugawa government and place the Japanese Emperor (Meiji) in power. The Meiji Restoration of 1868 brought the Meiji Emperor out of the shadows and into center of the government, and also set in motion an intense political, economic, and social change characterized by industrialization, modernization, and Westernization. The emperor brought in Western advisors to oversee the creation of Japanese factories, and infrastructure, and perhaps most important, a modern military. Japan’s success was quick and stunning. In 1875, just twenty-two years after Perry had used gunboat diplomacy to force Japan into unequal treaties, Japan saw political instability in Korea as an opportunity to show their newly gained might. Imitating the Perry incident, Japanese brought a gunboat to the Korean island of Ganghwa and was able to demonstrate their technological superiority in a brief firefight. The next year, Korea submitted to an unequal treaty with Japan that looked very similar to the Perry Convention that the Americans insisted Japan sign two decades earlier. Korea was forced to declare independence from China (prior to this, it had been an official tributary state of the Qing Dynasty. Though Korea was now independent and “open” to trade with all, Japan jealously guarded its neighbor. After Korea “opened” to the world in 1876, the Chinese presence did not suddenly leave. According to international law, Korea was independent and every nation had a right to trade, including the former Chinese overlords. This presence of the old power, China, and the new power, Japan, led to considerable tension on the Korean peninsula. A contest by proxy developed in the Korean leadership with China supporting the conservative rule and Japan supporting a progressive element. This all came to a head in 1884 when a pro-Japan faction within the Korean government attempted a coup d'etat. Chinese intervention checked this move, and the Li-Ito Convention was signed to avoid war between China and Japan. In 1894, however, a leader of the 1884 coup d’etat attempt and ally of Japan, Kim Ok-gyun, was lured to Shanghai and murdered. Shortly thereafter, China sent troops to aid the Korean king in putting down a peasant’s rebellion. Japan considered both of these actions an affront to the Li-Ito Convention and on August 1, 1894, the First Sino-Japanese War was declared. Foreign observers predicted that China would easily beat Japan because it had such a large army, but Japan surprised the world with a quick and decisive victory. The conflict ended with the Treaty of Shimonoseki, which mandated that China cede Taiwan, the Pescadores Islands, and the Liaodong Peninsula (which contains a very important warm water port called “Port Arthur”). Russia, because of the border it shares with China, had always been a player in the region and expressed concern with Japan being granted the Liaodong Peninsula because it could have given Japan a possible basis from which to slowly expand into China. Russia convinced Germany and France that it would be dangerous to allow Japan to keep the peninsula, and so these tree nations pressured Japan to accept a larger territory in a less strategically important location in exchange. This was known as the triple intervention. In general, the First SinoJapanese War was very important in Asia because it marked a shift in the balance of power in the region. China had always been the most powerful Asian state, but now Japan filled that role. With the Chinese defeat however, Japan had a new rival for dominance in Asia--the Russians. It was also the case that Britain was concerned about Russian encroachment into Asia. Britain had refused to join the triple intervention and in 1902, Japan and Britain signed the Anglo-Japanese Alliance mainly in the hope of checking Russian expansion. However, Russia continued to move further into Asia. In 1996, Russia had negotiated an alliance with China against Japan, and it exploited this to gain permission to build the Trans-Siberian Railway in Manchuria. Russia also took over the Liaodong Peninsula (the very same one they pushed Japan out of). This area was a short distance from Korea and Port Arthur was a valuable warm water port. (Russia faced problems storing its warships back home because the ports would freeze for several months out of the year!) Japan saw this as unfair, and also an indication that Russia planned to make this area a base for aggressive expansion into Korea. The Russo-Japanese War began on February 8, 1904 with a Japanese surprise attack on the Russian fleet stationed at Port Arthur. Just as had been the case in the First Sino-Japanese War, Japan won the Russo-Japanese War quickly and decisively. It was the first time in modern history that an Asian power had beaten a Western power in a military engagement. At this point, many Western nations began to fear the Japanese and their impressive, modern fighting force. The conflict was concluded by talks moderated by American president Theodore Roosevelt, which resulted in the Treaty of Portsmouth in September of 1905. According to this document, Japan was given the Liaodong Peninsula (including Port Arthur) as well as Russia’s former holdings in Manchuria (including the Trans-Siberian Railroad, which connected to Port Arthur). It also recognized Japan’s control over Korea (though Japan would not officially annex Korea until 1910). In 1908, President Theodore Roosevelt would have to mediate over another conflict involving Japan. Since shortly after the Meiji Restoration, Japanese laborers had been making their way to Hawaii and the West Coast of the United States, most notably California, where prejudice against Asians had already developed as a result of Chinese immigration following the Gold Rush in 1849. By 1882, Congress had permanently banned Chinese immigration. In 1906, San Francisco suffered an earthquake and fires that destroyed much of the city. In the aftermath of these, the San Francisco School Board moved to segregate children born of Japanese parents into substandard facilities in order to save the remaining functional schools for white children. Japan was outraged. President Roosevelt was concerned. He understood the reality of Japan’s powerful position and did not want to offend this nation. Roosevelt got the school board to compromise. It said that it would not segregate if Japanese immigration were stopped. Roosevelt then sent diplomats to meet Japanese counterparts and the result was the “Gentlemen’s Agreement” of 1908, which held that the United States would not outright ban Japanese immigration as long as Japan stopped issuing visas for laborers to come to the United States. This accord saved Japan, a very real power, the humiliation of having its nationals rejected entirely by the United States. The fact that the president of the United States had to negotiate between a local school board and a foreign nation (one that had one of the largest navies in the world) speaks to the intensity of anti-Asian discrimination on the West Coast. While all of this was going on, Japan had also been participating in the “open door” policy in China, an agreement to allow several Western powers and Japan equal access to trade in China, which was proposed by American Secretary of State John Hay in 1899. In fact, the American desire to retain its trading privileges in China and Asia were yet another reason that President Roosevelt sought the “Gentlemen’s Agreement” with Japan. The simple fact of Japan’s physical proximity to China, along with its new economic and military might gave it a stronger position in Asia than the United States had. Thus, Americans had to contend with Japanese power in the development and modernization of China. In 1910, Britain, Germany, France, and the United States created a four-power consortium whereby they would pool resources to develop China and then share in the profits. The next year this group grudgingly accepted both Japan and Russia as members and without a managerial capacity. Japan and Russia requested to join the consortium because they feared that it would take over the development of Manchuria in Northern China, where both nations had invested heavily. In 1913 however, President Woodrow Wilson, not wanting to add to a group that might inadvertently strengthen the position of Japan or a European power in China. Clearly, Japan’s strategic position in Asia was a concern to American policy makers.