9. The Pigou or real-balance effect is a mechanism by which an

advertisement

9. The Pigou or real-balance effect is a mechanism by which an increase in the real money supply

resulting from a fall in the price level can influence aggregate demand through increasing

autonomous expenditure. The Keynes effect on the other hand, is the normal channel by which an

expansion in the real money supply reduces interest rates and increases equilibrium output. Because

the price level is plotted on the vertical axis, the inclusion of a real-balance effect into the economy

will not in itself shift the AD curve but will affect the movement along the AD curve, i.e., the slope.

The slope of the AD curve is determined by how effective changes in real balances resulting from

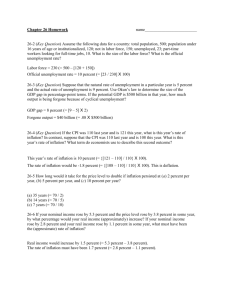

changes in the price level will be in influencing equilibrium output in the IS-LM model. As Figure 7E shows, if the reduction in prices from P0 to P1 is associated with both an expansion of the real

money supply and autonomous spending, both the IS and LM curves will shift rightward and

equilibrium output will rise to Y2 instead of Y1. This implies the flatter AD curve in the bottom

frame.Note that with the real-balance effect, an increase in the nominal money supply (all else being

equal) will result in a greater horizontal shift of the AD curve as well.

Figure 7-E

1

10. The real-balance effect was a counter-argument to the Keynesian observation that if autonomous

planned spending was very unresponsive to changes in the interest rate (steep or vertical IS curve) or

if interest rates became unresponsive to changes in the real money supply (flat LM curve), monetary

impotence resulted. The Keynesian response was that the deflationary process which increased

household real wealth may indeed make the AD curve steeper because of two effects associated

with deflation. First, households, seeing falling prices, may postpone planned autonomous spending in

expectation of prices falling further (the expectations effect). Secondly, the deflation tends to

redistribute wealth from debtors, who usually have a high propensity to consume, to creditors, who

usually have a lower marginal propensity to consume. This has the effect of reducing total aggregate

consumption, since for every dollar redistributed, a smaller fraction of it will be consumed (the

redistribution effect). The aggregate demand curve will be steeper when these effects are present

because the falling price level will produce smaller changes in autonomous planned spending and

income.

11. (a) The equation of the LM curve is r = [Y – 3(Ms/P)]/300. Substituting this into the IS equation

gives Y = k{A0 – 50[Y – 3(Ms/P)]/300}. Substituting in the given values of k, A0, and Ms and solving

for Y gives the equation of the AD curve: Y = 2880 + (720/P). Thus, when P = 1, Y = 3600, and when

P = 2, Y = 3240.

(b) Substituting the LM equation above into the new IS curve with the real-balance effect gives Y

= k{A0 + d(Ms/P) – 50[Y – 3(Ms/P)]/300}. Substituting in the given values of k, A0, d, and Ms and

solving for Y gives the equation of the AD curve: Y = 4114 + (1286/P). The effectiveness of realmoney-supply expansion caused by a reduction of prices is now greater. When P = 1, Y = 5400, and

when P = 2, Y = 4757. The AD curve becomes flatter with the inclusion of the real balance effect.

Chapter 8

1. The SP curve shows the level of real output that producers are willing to supply at every rate of

inflation. It is derived directly from the aggregate demand and supply model of Chapter 7. However, it

simply represents combinations of output level and inflation rate consistent with equilibrium in the

AD-SAS model and cannot by itself determine an equilibrium rate of inflation and output level; thus,

another relationship is needed to determine where the economy is along the SP curve. This

relationship is given by the definition that nominal GDP is equal to the price level times real GDP (X

= PY). This implies that nominal GDP growth must be the sum of the inflation rate and real GDP

growth (x = p + y). Because there always exists an inflation rate and level of output that satisfy this

growth equation at every given rate of nominal GDP growth, the combination of inflation rate and

output level that is on both the SP curve and that satisfies the growth equation represents the short-run

equilibrium of the economy. Starting from a position of long-run equilibrium, an acceleration in

nominal GDP growth must be divided between an increase in the inflation rate and real output growth.

This suggests that the economy’s short-run equilibrium position must move up and along the SP

curve. Similarly, the economy will move downward along the SP curve in response to a deceleration

in nominal GDP growth.

2. Because the growth equation is a definitional relationship, it’s always true that any given growth

rate of nominal GDP must be divided between the inflation rate and real GDP growth (x = p + y). If

nominal GDP growth exceeds the rate of inflation (x > p), then it necessarily follows that the growth

rate of real GDP must be positive (y = x – p > 0), and the level of output is growing at a positive rate.

Although this situation is consistent with a short-run equilibrium for the economy, long-run

equilibrium requires that the growth rate of real output be zero, i.e., it requires a constant real output

level, and accurate expectations of inflation. Therefore, changes in inflationary expectations will

2

adjust the economy until nominal GDP growth is completely “used up” by inflation (x = p and y = 0),

and the actual and expected inflation rates are equal (i.e., where Y = YN).

3. The two principal factors that determine how fast an economy adjusts to its new long-run

equilibrium position are (1) the slope of the SP curve and (2) the speed at which expected inflation

adjusts to actual inflation. The slope of the SP curve represents the responsiveness of real output to

inflation. The SP curve slopes upward because some raw materials prices are highly sensitive to the

level of aggregate demand and because producers tend to raise prices more rapidly when aggregate

demand is high. If the tendency of firms to raise prices during expansions is small, which implies a

flatter SP line, then an increase in nominal GDP growth will raise output by much more than the rate

of inflation. With backward-looking inflationary expectations, small changes in actual inflation will

cause small movements in expected inflation. As a result, the vertical upward shifts of the SP curve in

each period will be small as well, and this will lengthen the time real output can remain above its long

run natural level. Similarly, for any given slope of the SP curve, if inflationary expectations adjust

slowly (i.e., small j value in the adaptive-expectations formula), then the increase in inflation arising

from an acceleration in nominal GDP growth will also result in small vertical shifts in the SP curve in

each period of adjustment. Recall that “overshooting” in the adjustment loop occurs because inflation

reaches the long-run rate before inflation expectations have correctly adjusted to the actual rate. Thus,

slower adjusting inflationary expectations implies a larger degree of overshooting during the

adjustment process. This suggests that, while a flatter SP curve lengthens the adjustment time by

causing a “flatter” loop, slow adjusting inflationary expectations lengthen the adjustment time by

causing a “taller” loop. With a given slope and speed of expected inflation adjustment (j value), the

speed at which the economy adjusts to long-run equilibrium depends on the size of the acceleration or

deceleration of nominal GDP growth itself. In the case of disinflationary policy, it is clear that a

sudden “cold turkey” nominal GDP deceleration quickly reduces the rate of inflation, but at the

expense of a more severe recession than a more “gradual” deceleration. The policy implication here is

that a quicker adjustment is desirable only if the costs of a gradual movement away from the current

condition of the economy (e.g., high inflation) sufficiently outweighs the costs associated with a faster

adjustment to long-run equilibrium.

4. The SP curve graphically represents the level of real output that can be sustained at an inflation rate

generated from a continuous expansion (or contraction) of aggregate demand. Thus, the SP curve will

only slope upward if nominal wages are not completely and immediately flexible. Starting from a longrun equilibrium, if nominal wage contracts incorporate an expected rate of inflation less than the actual

rate, then the growth rate of prices, or the inflation rate (p), will be greater than the growth rate of

nominal wages (w). Thus, the growth rate of real wages (w – p) will be negative, implying that the

level of real wages (W/P) will fall below its original equilibrium level. Therefore, the reason why the

economy is able to be on the SP curve and above the natural level of output when inflation expectations

are below the actual inflation rate is that the real wage will be lower than the long-run equilibrium real

wage.

5. The inflation rate that workers expect during nominal wage contract negotiations is precisely the

growth rate of nominal wages incorporated into the contracts. With backward-looking expectations,

any acceleration in nominal GDP growth will cause an initial acceleration of inflation and be

accompanied by an increase in the expected inflation rate in the next period that wage contracts are

renegotiated. This will push up the growth rate of nominal wages and shift the SP curve upward,

reflecting the fact that firms will supply less output at the higher nominal wage rates. In the short run,

because the growth equation (x = p + y) must be satisfied, the lower growth rate of real output must

be accompanied by a further increase in the inflation rate to maintain the same growth rate of nominal

GDP. As the expected inflation rate adjusts to the actual rate of inflation in the long run, output will

3

remain at its natural level while the long-run equilibrium inflation rate will be equal to the new higher

growth rate of nominal GDP. Note that even if the increase in the expected inflation rate were due to

“autonomous” causes instead of an expansion of aggregate demand, the actual inflation rate would

still increase in the short run for the same reason. However, the long run effects in this case will

depend on any further changes in inflation expectations and the response of policymakers.

6. The first step in the development of the SP model was to establish the relationship between output

and inflation that is implied by the aggregate demand and supply model in Chapter 7. The result was

the upward-sloping SP curve which relates the level of output firms are willing to supply to the rate of

inflation. The second step was to use the definition that nominal GDP growth is equal to the sum of

the inflation rate and growth rate of real GDP to determine precisely where the economy is on the SP

curve in each period. The SAS-AD model of Chapter 7 assumed nominal wages eventually “adjusted”

to clear the labor market following aggregate demand expansion without specifying how they

adjusted. This chapter considers alternative methods by which workers form expectations of inflation.

Instead of imposing forward-looking rational formation of expectations, the SP model assumes the

more realistic backward-looking adaptive expectations approach. The essential difference between

these methods of expectation formation is that under the adaptive approach the expected rate of

inflation in the SP model is the inflation rate that workers expect at the time long-term wage

contracts are negotiated. Any change in the “day-to-day” inflation expectation of workers during the

period the wage contract is binding is irrelevant since such changes in expectations cannot alter

nominal wages until the contract expires.

7. Backward-looking expectations imply that workers and firms form their expectations based on

events that have already occurred instead of predictions of the future. The text lists two important

reasons why rational firms and workers may form their expectations of inflation by looking backward

rather than forward. First, there is no reason to believe that an acceleration in nominal GDP growth

will be permanent, so that workers and firms may take the precautionary measure of waiting before

acting on the change immediately. Second, rational workers and firms find it beneficial to enter into

long-term wage and price agreements. Since this implies that wages and prices adjust gradually,

workers form their expectations based on this slow adjustment process following an acceleration in

nominal GDP growth.

8. Before the 1960s, the behavior of the inflation rate was mainly procyclical along the SP curve.

However, the acceleration of nominal GDP growth that began in 1964 eventually led to a

simultaneous acceleration of inflation and a falling output ratio (Y/YN) by 1969. The dynamic SP

model explains this puzzling observation with the inflation“adjustment loop.” The acceleration of

nominal GDP initially boosted both the output ratio and the inflation rate, but by 1969 expected

inflation had not yet caught up with actual inflation so that the inflation rate “overshot” its long-run

equilibrium level. The second classic demonstration of the SP model was the disinflation of the

1980s. The “cold turkey” reduction of nominal GDP growth in 1981–82 pushed the economy through

a counterclockwise loop and resulted in the immediate reduction of the inflation rate at the expense of

the severest recession and highest unemployment rates of the post-war era.

9. The dynamic analysis of demand and supply shocks in Chapter 8 converted the static AD-SAS

framework into a dynamic model of the output level and the inflation rate. Through the incorporation

of adaptive expectations, the dynamic SP model demonstrates that the degree of price and wage

flexibility and the rate at which expectations of inflation adjust to the actual inflation rate play an

important role in generating “inflation loops.” This causes any permanent acceleration in aggregate

demand or supply shocks to generate fluctuations in the rate of unemployment and inflation.

Furthermore, the short-run effects of inflation and unemployment, following a supply shock, depend

4

on the nominal GDP growth response of policymakers. Therefore, the SP model does offer an

explanation for the cause of the highly variable rate of inflation (Puzzle 2); however, because

fluctuations in the output ratio generate cyclical unemployment, the SP model is able to explain the

variability of the unemployment rate (Puzzle 1) but not its high rate. That is addressed in Chapter 12’s

discussion of the natural rate of unemployment.

10. (a) A simultaneous rise in the rate of inflation and fall in the output ratio implies that there is a

supply shock or an increase in the expected inflation rate which shifts the SP curve leftward with a

fixed nominal GDP growth rate. These movements are pure “supply” inflations and classic examples

of them include the food and energy supply shocks of 1973–74, along with the removal of price

controls in 1974, and the supply shocks of the late 1970s. “Stagflation” in 1969–70 provides an

example of an adjustment loop that did not involve supply shocks. (b) A constant inflation rate

associated with an increase in the output ratio implies that the SP curve shifted rightward with a

simultaneous increase in demand caused by an acceleration in nominal GDP growth. The classic

example of this was the extinguishing policy of the Fed following the price control program of 1971–

74. The economy’s experience over the period 1993–96 also displays constant inflation accompanying

a rising output ratio. (c) A simultaneous increase in both output and inflation implies that there is an

acceleration in nominal GDP growth along a stable SP curve. These movements are pure “demand”

inflations, and examples include the 1963–66 tax cuts and the beginning of Vietnam wartime

spending, and the “second-wind” reacceleration of inflation in 1987–89. A classic example of a

“demand deflation” is the deceleration of nominal GDP growth which triggered the 1981–82

recession.

11. In a demand-induced inflation, if an increase in the expected rate of inflation is fully incorporated

into labor contacts, then there will be an increase in the growth rate of nominal wages. Firms will

respond by reducing the output they are willing to supply at every given rate of inflation, and the SP

curve will shift upward.Supply shocks will have the same effect on the SP curve. The essential

difference, however, is that supply shocks move the economy along a given labor supply curve (which

corresponds to a lower production function) at every price level(assuming no real-wage rigidities),

while an increase in the nominal wage rate moves the economy along a given labor demand function

(which corresponds to the original production function) at every price level. Although the two effects

are distinct, they may be related. If a supply shock is expected to be permanent, higher expectations of

inflation could continue to shift the SP curve upward and result in a permanently higher rate of

inflation.

12. The statement is inaccurate in two important ways. First, a supply shock that lasts for only one

period will cause the SP curve to shift back to its original position only if inflationary expectations

remain constant. If the expected rate of inflation responds to the one-shot increase in the actual

inflation rate, then the SP curve after the supply shock ends will be higher than the original SP curve,

implying a permanent acceleration of inflation and a lower output ratio (assuming a neutral nominal

GDP growth policy). Second, if the one-period supply shock were permanent and if inflationary

expectations were to remain constant, then the output ratio and the inflation rate would return to their

original equilibrium values. However, without a counteracting downward-shifting SP curve

characteristic of temporary supply shocks, the supply shock’s “direct effect” of lowering the natural

level of output and increasing the level of prices would remain. Furthermore, if policymakers respond

to the one-period supply shock with an accommodating or neutral policy, then the original level of

output would not be attainable at the same rate of inflation.

5

Appendix to Chapter 8

1. (a) p = [p-1 + g ( Yˆ -1 + xˆ ) + z]/(1 + g), Yˆ = Yˆ -1 + xˆ – p.

(b) xˆ = x – yN = 11 – 5 = 6. In the long-run p = xˆ = 6.

(c) (i) xˆ = 6, p = [2 + (0 + 6)]/2 = 4, Yˆ = 0 + 6 – 4 = 2.

(ii) xˆ = 2, p = [4 + (2 + 2)]/2 = 4, Yˆ = 2 + 2 – 4 = 0.

(iii) xˆ = 2, p = [4 + (0 + 2)]/2 = 3, Yˆ = 0 + 2 – 3 = –1.

(d) For year 2, set xˆ = 2: p = [4 + (2 + 2)]/2 = 4, Yˆ = 2 + 2 – 4 = 0.

For year 3, set xˆ = 4: p = [4 + (0 + 4)]/2 = 4, Yˆ = 0 + 4 – 4 = 0.

2. (a) xˆ = 9, p = [9 + 2 (0 + 9) – 3]/3 = 8, Yˆ = 0 + 9 – 8 = 1.

(b) This implies that the output ratio will be fixed at Yˆ = 0. since Yˆ = Yˆ -1 = 0, xˆ = p. Thus, we

have p = [9 + 2 (0 + p) – 3]/3 ⇒ 3p = 6 + 2p ⇒ p = 6.

(c) This implies that p = 9. Thus, 9 = [9 + 2 (0 + xˆ ) – 3]/3 ⇒ xˆ = 10.5, Yˆ = 0 + 10.5 – 9 = 1.5.

(d) Since Yˆ = Yˆ -1 = 0 for an accommodating policy, xˆ = p. Thus p = [6 + 2 (0 + p)]/3 ⇒ 3p = 6

+ 2p ⇒ p = 6.

Chapter 9

1. This statement incorporates several important concepts developed over the last few chapters. First

is the straightforward idea that an acceleration in the rate if nominal GDP growth will increase the

inflation rate and, to the extent that the demand shock was unexpected, unanticipated inflation.

Second is the important role of distinguishing between the real and nominal rate of interest in

determining the costs of unanticipated inflation. Because unanticipated inflation is not incorporated

into fixed nominal interest loans, it will redistribute wealth from wealthy creditors to middle-class

debtors by reducing their real interest income. Finally, the fact that every dollar of real income that is

redistributed will increase the consumption of the middle class by more than the fall in consumption

by the wealthy implies that aggregate consumption will increase as a result of this redistribution of

wealth. Therefore, the net effect of the unanticipated inflation will be further to aggravate inflation by

further increasing nominal GDP growth through consumption spending.

2. This is a false statement. First, it does not explicitly recognize the distinction between the costs of

unanticipated inflation and the costs of anticipated inflation. Indexation is no cure for inflation itself;

it is simply designed to eliminate the costs of unanticipated inflation, i.e., it is designed to protect

savers from a redistribution of their wealth to debtors. It does so by making expectations of inflation

irrelevant to the individual decision-making process and to the inflation-unemployment process. It

may even introduce more efficiency into the system by freeing resources previously devoted to

computing expectations and overcoming uncertainty. However, indexation does nothing to protect

individuals from the costs of anticipated inflation resulting from the “shoe-leather” cost of lower real

balances and the possible change in relative prices. Furthermore, indexation will likely magnify the

sensitivity of prices to both demand and supply shocks by causing aggregate demand and supply to

become less responsive to price changes and thus making the AD and SAS curves steeper. This is

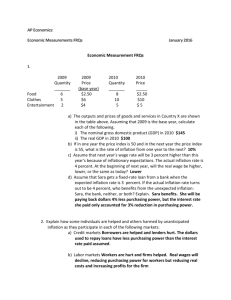

shown in Figure 9-A, where, in the left frame, a given supply shock along the steeper ADs curve

rather than the flatter ADf curve increases the volatility of prices by (P2 – P1). The same result holds

true for demand shocks along a steeper SAS curve (right frame of Figure 9-A). Therefore, indexation

may actually worsen the costs of anticipated inflation. Note, however, that with indexation the

6

fluctuations in aggregate output that accompany supply and demand shocks will be smaller than they

would be in the absence of indexation.

Figure 9-A

3. (a) The expected rate of interest is calculated by using the expected rate of inflation. Thus, from

the definition of the expected real interest rate, we have re = i – pe = 10% – 5% = 5%.

(b) Since the actual real interest rate is calculated from the actual inflation rate, we need the

growth equation, introduced in Chapter 8, to determine the actual inflation rate: x = p + y p = x –

y = 8% – 2% = 6%. Therefore, the real rate of interest is r = i – p = 10% – 6% = 4%.

4. Yes. The relationship between the real and nominal interest rate is given by i = r + p. If there

were a reduction in the growth rate of the nominal money supply, the resulting upward pressure on the

real interest rate could be, given a sufficiently steep aggregate supply curve, completely matched by

the resulting deflation of prices. Therefore, nominal interest rates may remain stable or even fall as the

real interest rate rises.

5. The actual unemployment rate has three components: turnover (frictional) and mismatch

(structural), which make up the natural rate of unemployment, and cyclical. From Okun’s Law, this

relationship can be expressed as U = UN – h Yˆ or U – UN = –h Yˆ . Thus, an acceleration in nominal GDP

growth through stimulative monetary or fiscal policy will be able to raise Yˆ temporarily above zero,

and thus lower the actual rate of unemployment below its natural rate. This temporary situation arises

when the expected rate of inflation (pe) is fixed, so that an acceleration of nominal GDP growth will

increase both the inflation rate and output ratio along a given SP curve (p = pe + g Yˆ + z). Because

subsequent adjustments of the expected rate of inflation will eventually leave the economy at its

original level of Yˆ in the long-run, stimulative demand policies will cause permanent inflation

without being able permanently to reduce the actual rate of unemployment below its natural rate.

6. The three types of unemployment are turnover, mismatch, and cyclical. As mentioned in the

answer to the previous question, stimulative demand policies will only be successful in temporarily

reducing the cyclical component of the unemployment rate. However, if the unemployment is

turnover, then stimulative demand policies may have little or no effect on the rate of unemployment.

The type of government policies pursued to reduce the rate of mismatch unemployment greatly

depends on the specific factors which prevent willing workers from filling available job vacancies. If

the mismatch unemployment arises from the lack of skills, then the available policy options of the

7

government include the promotion of better public education, subsidies for firms to train unskilled

workers, and more government-financed training programs. If the mismatch unemployment arises

from the immobility of the labor force, then the government can (1) offer a better employment service;

(2) subsidize displaced workers to move to where jobs are available; and (3) “move the jobs to the

people” by establishing industrial “enterprise zones” which promote the relocation of factories. The

turnover component of unemployment is the least severe of the three types of unemployment and

mainly consists of individuals involved in “job search.” The government policies that may reduce the

turnover unemployment rate include establishing better employment agencies which provide better

information to shorten the search period, and reducing the economic incentives which prolong search

activity. However, the elimination of “productive” search activity is not desirable. Note also that

because mismatch and turnover unemployment are not mutually exclusive, government programs

designed to reduce one may actually increase the other. For example, policies designed to promote a

greater mobility of labor and lower the mismatch unemployment rate may encourage more individuals

to quit their current jobs to search for better ones, and this increases the turnover unemployment rate.

7. The analysis of inflation in Chapter 8 deals with the effects of demand and supply shocks in

explaining fluctuations in the output ratio and the inflation rate. Because the cyclical component of

unemployment is negatively influenced by fluctuations in the output ratio, these destabilizing demand

and supply shocks also explain fluctuations in the unemployment rate. Therefore, Chapter 8 offers a

solution to the first macroeconomic puzzle regarding the variability of the unemployment rate.

The purpose of the analysis in Chapter 12 is to explain why the unemployment rate is higher than

zero. It does this by first noting that the principal cause of the high actual rate of unemployment is a

high natural rate of unemployment. Then it provides a detailed discussion of the causes of the high

natural rate by decomposing it into mismatch and turnover unemployment. Although discretionary

monetary and fiscal policy can be used to reduce the variability of the unemployment rate, only

policies directly affecting the structural and institutional environment of the economy can help in

reducing the natural rate of unemployment.

Chapter 10

1. (a) If each new worker were as productive as the average worker currently in the United States,

there would be no effect on GDP per capita. If immigrants were more productive, GDP per capita

would rise; if immigrants were less productive, GDP per capita would decline.

(b) There would be an increase in the amount of capital in the economy because of the

government surplus (tight fiscal policy) and the lower interest rate (easy monetary policy). This

increase in the growth of capital per worker will cause an increase in the rate of growth of real GDP

per person.

(c) There would be an increase in both individual and business saving, causing a temporary

increase in the rate of growth of capital per worker and the rate of growth of real GDP per person until

the economy adusts to its new steady state.

(d) The value of the autonomous factor (“the residual”) would increase. Even without changing

the amount of labor or the amount of capital, the level of real output would increase. Thus, the rate of

growth of real GDP per person would increase.

(e) There would be an increase in the rate of growth of capital per worker, causing an increase in

the rate of growth of real GDP per person.

8

2. The original Harrod-Domar model of economic growth was developed in two fundamental steps.

First, the identity that saving equals investment (S = I) was combined with the definition of

investment to arrive at an identity relating the level of national saving to the growth rate of capital and

the capital depreciation rate: S = [( K/K) + d]K. Second, the steady-state condition that the growth

rate of capital stock must equal the population growth rate (k = n) was incorporated to develop the

theoretical steady-state condition that the saving per unit of capital equals the sum of the population

growth rate and the depreciation rate: sY/K = n + d. However, this model was said to have “knifeedge stability” in that there was no equilibrating forces guiding the seemingly independent factors to

be consistent with the steady-state condition. Solow solved this problem by incorporating the perperson production function Y/N = f(K/N) into the model and recognizing that when K/N is growing

faster than Y/N, the capital needed to equip new workers with the same capital per worker as existing

workers and to cover the depreciation of capital is in excess of total saving, so that K/N will eventually

fall until ( K/N) = 0 and the steady state condition is satisfied. Thus, the important aspect that the

production function added was the property of diminishing returns to the capital-labor ratio.

3. According to the Solow growth model, the growth rate of real output must be equal to the

population growth rate in the steady state. Thus, an increase in the growth rate of the population (n)

causes the growth rate of output (y) to rise by exactly the same amount after the economy reaches

its new steady state.However, what matters to the new steady-state level of Y/N depends on the

relative growth rates of population and output during the transitional period between steady states.

From an initial steady-state equilibrium at Point E (Figure 10-A), an increase in the population growth

rate at each level of K/N implies that it will take a greater capital-labor ratio to maintain the same Y/N

ratio in the steady state. This will rotate the steady state investment line counterclockwise from (n +

d)K/N to (n' + d)K/N and cause the growth rate of output to be temporarily lower than the population

growth rate. Finally, as the economy reaches the new steady state at Point E', the population and

output growth rates are once again equal, although higher than their original rates, and (Y/N)0 falls to

(Y/N)1.

4. The term “technological growth factor” or “technological change” was criticized for prejudging

the sources of growth. There are many cases that involve the growth of output relative to the growth in

inputs unrelated to “technological change.” Therefore, the term “residual” or “multi-factor

productivity” is preferred. Some of the sources of residual growth not related to technological change

include greater education changes in demographic composition, a movement of the labor force away

from rural labor and to industrial labor, the effects of externalities such as crime and pollution,

advances in research and innovation, and improvements in labor quality.

9

Figure 10-A

5. Yes. In fact, production functions are usually assumed to be characterized by both diminishing

returns and constant returns to scale (e.g., the Cobb-Douglas production function). A production

function has the property of diminishing “marginal” returns when the employment of each additional

unit of one of the input factors, while holding the others constant, reduces the amount by which total

output increases (i.e., the marginal product of that input factor). However, the concept of constant

returns to scale implies that if all of the input factors are increased by a certain proportion, then the

output level will rise by exactly that same proportion. In mathematical terms, functions of this type are

called “homogeneous of degree one” or “linearly homogeneous.” To see these relationships more

clearly, consider the standard Cobb-Douglas production function: Y = AKbN1-b, b < 1. Because the

capital elasticity of real GDP, b, is less than one, every unit increase in the capital stock while holding

the quantity of labor fixed will increase output by less, i.e., the change in output falls as the capital

stock continues to rise. Thus, this production function exhibits diminishing returns in capital, and the

same result is true of changes in the quantity of labor. However, because the labor elasticity of real

GDP is (1 – b), every one percent increase in both capital and labor will increase the level of output

by b + 1(1 – b) = 1 percent. Thus, this production function also exhibits constant returns to scale.

Note also that while these two concepts are identical in functions of one independent variable, they

are generally two distinct concepts.

6. The most important factor in determining the level of private investment in an economy is the

level of national saving, which is composed of personal, business, and government saving. Thus, the

federal budget deficit and the current account deficit play a very important role in determining future

economic growth. The federal budget deficit influences growth because it directly influences national

saving. The current account deficit matters because a buildup of debt to foreigners will reduce the

future output available by requiring future Americans to pay an increasing fraction of their income as

interest to foreigners.

Chapter 11

1. Labor’s share of national income is (W/P)/(Y/N). That labor’s share of national income is less than

1 implies that the average real wage (W/P) is less than average labor productivity (Y/N). This means

that a portion of labor’s average productivity accrues to owners of other factors of production as

compensation for their contribution to the production of output.

2. If firms are unwilling to lay off workers during business cycle recessions and hire them back

during expansions, the level of employment will be less variable than output over the business cycle.

This will cause the growth of labor productivity (y – n) to be procyclical. During recessions output

will fall by a larger relative amount than employment, causing (Y/N) to decline, while during

expansions output will rise relatively more than employment and (Y/N) will rise.

3. No single explanation (or even reasonable combination of single explanations) has been offered to

explain the slowdown in U.S. productivity that is compatible with the available data. Thus, attempts to

explain the U.S. slowdown using reductions in R&D expenditure, of labor force quality, or energy

prices, simply do not offer much in the way of robust explanations. Thurow’s point is that the current

U.S. economy is so complex and the various regions and industries are so vastly different that it is

unlikely that a single explanation can suffice.

10

4. Some people feel that the steady increase in foreign trade, frequently called the globalization of

the world economy, has the effect of creating competition between foreign workers and domestic

workers. To the extent that this is true, it would directly slow the growth of the real wage, and

indirectly, as in the bottom frame of Figure 11-8, slow the growth rate of productivity.

5. (a) An increase in investment in public infrastructure and private capital would raise capital per

worker and labor productivity. This would shift the labor demand curve upward and, given no change

in the labor supply curve, cause the real wage rate to rise. Thus the change in labor productivity

causes the rise in the real wage rate.

(b) A reduction in the flow of immigrants to the United States will shift the labor supply curve to

the left and, with no change in the labor demand curve, cause the real wage rate to rise. With workers

now more costly to employ, firms will reduce their level of employment. With fewer workers

employed, capital per worker and output per worker will be greater. This case differs from that in (a),

however, because here the increase in real wages is the cause rather than the result of the rising labor

productivity.

Chapter 12

1. The fundamental problem with these two statements is that neither accurately represents the true

burden of the public debt. The true burden that arises from the debt is that it absorbs national saving

and thus reduces the funds available for private investment. If the government deficit finances

consumption goods rather than investment goods, the public debt will lower the current stock of

capital and thus reduce the economy’s ability to support a higher level of consumption and a higher

standard of living in the future. The second fundamental flaw with both of these statements is that

they fail to distinguish between government debt that is domestically held and government debt that is

held by foreigners. If the debt is domestically held, the second statement’s criticism of the first is valid

because the interest payments on the debt involve a transfer of income among domestic citizens, i.e.,

“we owe it to ourselves”; however, the second statement ignores the possibility of the debt being held

by foreigners. The analysis of debt held by foreigners is similar to that held by domestic residents in

that it depends on whether the debt is used to finance government purchases of consumption or

investment goods. Also, the foreign debt has the added burden of transferring real resources away

from the domestic economy to finance the interest payments on the foreign debt, and this will reduce

future growth in real consumption.

2. The Barro-Ricardo equivalence theorem holds that any deficit-financed tax cut will increase

current private saving instead of current consumption because of the implied future tax liability

required to pay off the interest on the debt. Because the time horizon or the implied future taxes is

likely to be much longer than the lifetime of those receiving the tax cuts, Barro stressed the

importance of the bequest motive. The central assumption here is that if the current generation cares

about the burden of future taxes on their children, they will increase their current saving and pass it

along as bequests to their children. The prediction of the Barro-Ricardo equivalence theorem is very

different from the standard Keynesian analysis in that it denies that government bonds represent net

wealth, so that tax-based discretionary fiscal policies will be completely ineffective in influencing the

level of aggregate demand, output, and employment. However, this proposition ignores the

observation that individuals may be liquidity constrained and face imperfect capital markets.

3. The solvency condition places a limit on how much the debt-to-GDP ratio can feasibly grow by

concluding that the government can only continue to finance its deficits by issuing more debt if the

growth rate of real output equals or exceeds the real interest rate on the bonds. This condition implies

11

that if the real interest rate exceeds real output growth, then financing the interest payments on the

existing debt by issuing more debt cannot be sustained forever. Thus, because current debt financing

implies that the eventual money financing will have to cover even larger interest payments on the

national debt, debt financing today may eventually be more inflationary than money financing today.

Figure 12-A

4. The short-run and long-run effects of a government budget deficit greatly depend on how the

deficit is financed. As specified by the government budget constraint, the two fundamental methods

available to finance the total government budget deficit are bond (or debt) financing and money

financing. The essential difference is that when an increase in government expenditures is financed by

bonds, IS1 shifts outward to IS2 and private spending is crowded out by an increase in the interest

rate from r1 to r2 along LM1 in Figure 11-A. However, money financing has a greater effect on the

expansion of output, since both the IS and LM curves shift outward, so that the crowding-out effect

caused by higher interest rates is diminished or completely eliminated. In Figure 12-A, the shifts of

IS1 to IS2 and LM1 to LM2 are shown holding the interest constant at r1. It is for this reason that

money financing is recommended when the economy is weak while bond financing is recommended

when the economy is strong. The alternative methods of deficit financing also have different effects in

the long-run as well. Because bond-financed deficits that are not used for purchase of investment

goods will reduce total productive investment spending, they impose the burden of lower future

economic growth. On the other hand, although deficits financed by money creation avoid this burden

of crowding out private investment, they could impose significant costs to society by causing an

acceleration of inflation.

5. The fact that real GDP rose after the Reagan tax cuts does not confirm the validity of supply-side

analysis because it fails to specify whether the tax cuts and the increase in real GDP were linked as

hypothesized by the supply-side economists. To determine this, it matters a great deal what happened

to the saving rate, labor productivity growth, the real interest rate, and the budget deficit. Supply-side

economists predicted that the tax cuts would lead to an increased saving rate, which would reduce real

interest rates and fund productivity-enhancing investment, and that the cuts would be self-financing

because they would stimulate enough additional production to generate the income from which more

taxes would be collected even at a lower tax rate. The mere fact that real GDP grew following the tax

cuts is not sufficient to tell us whether the growth proceeded as expected by the supply-siders. It is

possible, for instance, that the real GDP grew not from any boost to the supply-side of the economy,

but rather that it resulted from a boost to aggregate demand as predicted in the simple Keynesian

12

model. The Keynesian growth process, however, is much different than that envisioned by the supplysiders. In fact, it appears that the growth that occurred following the tax cuts is better explained by the

simple Keynesian theory of income determination than by the theories of supply-side economics. The

saving rate failed to rise, labor productivity growth failed to increase, and the real interest rate and the

budget deficit both rose, all of which support a Keynesian rather than supply-side explanation of the

growth that followed the Reagan tax cuts.

Chapter 18

1. Inflation was curtailed by stringent price controls, and interest rates were pegged by the Fed.

2. Federal Reserve action led to reduced interest rates, which stimulated housing and automobile

purchases.

3. In an attempt to curb the 1956–57 acceleration of inflation, the Fed allowed interest rates to rise.

This led to the recession of 1957–58, during which unemployment rose to its highest postwar level.

4. The monetarists’ pessimism that activist policy would do more harm than good was reinforced by

the following events of the 1960s: the long legislative lags for both fiscal and monetary policy, failure

of the income-tax surcharge to slow the economy, and overly tight monetary policy’s adverse effect on

the economy.

5. The Fed began targeting the money supply, rather than interest rates, so instability in private and

government spending resulted in interest-rate instability.

6. The oil and food supply shocks caused inflation and unemployment to be positively correlated,

while the short-run Phillips curve predicted a negative correlation.

7. The triangle refers to demand shocks, supply shocks, and the expectations-adjusted Phillips curve.

The development of the expectations-adjusted Phillips curve, coupled with the natural-rate hypothesis,

and demand and supply shocks was a response to the supply shocks of the 1970s. As noted in the

answer to the previous question, the “standard” Phillips curve was unable to explain the direct relation

between the unemployment rate and inflation that occurred during the supply shocks.

8. The Fed appeared to be following an unannounced policy of targeting real GDP growth

throughout much of the 1980s. In the 1990s, it has targeted the rate of unemployment, trying to keep it

close to its natural rate. But the Fed also monitors inflation. If inflation is not accelerating,

unemployment is not above its natural rate.

9. Foreign trade makes up a much greater share of the GDP of European countries than of the U.S.,

but the share of net exports in U.S. GDP has been growing.

13