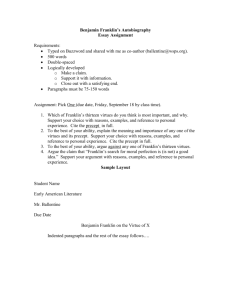

Franklin's Model of Virtue and its Implications for Future Generations

advertisement

Franklin’s Model of Virtue and its Implications for Future Generations Michael A. Molinari A More Perfect Union: The Origins and Development of the U.S. Constitution Charms, Bi-County, North River, Year One September 23, 2010 2 One of Benjamin Franklin’s greatest legacies left for posterity in his Autobiography is his devotion to living a moral and virtuous life. Franklin’s dedication provides a springboard from which he has risen to greatness. This rise to prominence provides future generations of Americans with a model of virtuous achievement. His model of virtue, if adhered to, may lead to self improvement and upward mobility in our contemporary society. His impact on our world is often times overlooked as he is responsible for mainstreaming the idea that the working class should be glorified, rather than looked down upon as was the case in aristocratic Europe. His method of achievement by virtuous means continues to provide a template for success in our fast-paced world. Franklin’s legacy pervades many aspects of American life even including American pop-culture. Most importantly Franklin was aware of his own shortcomings, and by his own admission, he was imperfect, this realization led Franklin to pursue perfection throughout his life. This noble pursuit led Franklin to many great scientific, philosophical and political achievements culminating in Franklin’s eventual veneration as a champion of the working class. Franklin becomes an indispensable founding father whose humble origins were hardly indicative of the monumental role he would play in the founding of our nation. In Part One of his Autobiography Franklin stated his reason for writing his life story for posterity. His words vindicate his unique rise to prominence made possible in America during the Revolutionary Era, a rise that was uncommon during the 18th century. Franklin was proud of his lowly origins as a printer’s apprentice and hoped that his rise to affluence and political prominence would provide an exemplary model for future generations born in obscurity; Franklin states this as the reason for writing his Autobiography: 3 Having emerg’d from Poverty and Obscurity in which I was born and bred, to a State of Affluence and some Degree of Reputation in the World, and having gone so far thro’ Life with a considerable Share of Felicity, the conducing Means I made use of, which, with the Blessing of God, so well succeeded, my Posterity may like to know, as they may find some of them suitable to their own Situations, and therefore fit to be imitated (sic).1 Many Americans sought to emulate Franklin’s rise to affluence from obscurity following the Revolution and contemporary Americans seek to emulate Franklin today. American rapper Puff Daddy’s song It’s All About the Benjamins glorifies rising from obscurity to prominence, cementing the rags to riches story for future generations of American youths. Franklin’s appeal to ambitious youths and his methods for achieving prominence through virtue and industry are reasons for sharing his Autobiography for future generations. Franklin’s rise from an indentured printer’s apprentice to a founder of our nation secures his reputation as an indispensable American whose rise from obscurity to greatness is a story future generations continue to emulate. From the start, Franklin’s Autobiography is a guidebook for “self-made” men. Since its original publication following Franklin’s death in 1790 it continues to be widely read. Franklin’s Autobiography not only explains Franklin’s rise to scientific prominence, which led to his success in promoting the American Revolution abroad as an internationally renowned scientist and philosopher, but also provides an indispensable blueprint for millions of Americans who want to glorify their humble origins as they too pursue the American dream. Franklin’s life will not only lead to the rise and eventual glorification of America’s “middling sort,” but also to the rise and glorification of the “middling sort” in France during the French Revolution. Brown University Professor Gordon Wood argues, “if Washington was indispensable to the success of the Revolution in America, Franklin was indispensable to the 4 success of the Revolution abroad.”2 Franklin essentially achieved rock star status in Europe as a result of his work with electricity, greatly increasing his political strength abroad during the American Revolution. Without Franklin’s internationally renowned status it would have been unlikely Louis XVI of France would have supported the American Revolution at a cost of over a billion livres, a sum that will eventually bankrupt France causing the French Revolution in 1789. For the aforementioned reasons, Franklin continues to be an indispensable American and French hero while serving as an exemplary model of American upward mobility. Even people who read fragments of Franklin’s Autobiography prior to its official publication realized its value as a guide for America’s ambitious youths. Abel James, an old Quaker friend of Franklin said, “no Character living nor many put together, who has so much in his Power as Thyself to promote a greater spirit of Industry and early Attention to Business, frugality and Temperance with the American youth (sic).”3 Another friend, Benjamin Vaughan, told Franklin, “your life will give for the forming of future great men; and in conjunction with your Art of Virtue, (which you design to publish) of improving the features of private character, and consequently of aiding all happiness both public and domestic.” He went on to tell Franklin that his biography would not only teach “self education” but the education of a “wise man” as well.4 Veneration from Franklin’s friends and contemporary historians alike compel Americans to see Franklin as a man to be emulated. It is important however that we analyze Franklin’s method of achieving affluence by virtuous means to prevent impressionable youths from attempting to achieve the “Benjamins” in immoral ways. Franklin’s reliance on morality and virtue allowed many of Franklin’s dreams to come to fruition. Franklin’s strict moral compass is made apparent in his Autobiography. Without this strict moral compass many of the remarkable events in Franklin’s life may not have occurred, 5 this fact should be stressed to the youths of today. One virtue Franklin stresses in his Autobiography is the virtue of humility. Interestingly, Franklin begins his story by admitting to the sin of vanity and then writes a humble and humorous epitaph, which includes a statement on redemption: The Body of B. Franklin, Printer; Like the Cover of an Old Book, Its contents torn out, And stript of its Lettering and Gilding, Lies here, Food for Worms, But the Work shall not be wholly lost: For it will, as he believ’d, appear once more, In a new & more perfect Edition, Corrected and amended By the Author. He was born Jan. 6. 1706. Died 17 5 Franklin modestly places “Printer” as his profession as opposed to the many other great professions and titles he possessed throughout his life as well as the great deeds he accomplished. Franklin could have listed his founding of the Junto, his Almanac, the founding of the American Philosophical Society, his experiments with electricity, his role as Post Master General, his drafting of The Albany Plan of Union, his two honorary Doctorate degrees, his role as a commissioner to France during the American Revolution and at the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1783, to name but a few. Even though Franklin wrote the epitaph in 1771, prior to his many successes as an American ambassador to France, the fact that he did not go back and 6 amend the epitaph proves the modest and humble nature of his character. Franklin’s epitaph humbly admits that his life was an imperfect one that will one day be amended by the author, that is to say by God in Franklin’s afterlife. It is important to analyze Franklin’s belief in God, as it is a driving force throughout his life and a possible explanation for his obsession with morality and virtue. Franklin goes so far as to list Socrates and Jesus as his models of humility, and stressed using them as a model for living an exemplary life.6 Franklin’s religious views led to great introspection resulting in Franklin’s constant quest for self-improvement. Franklin states his religious views as follows: I never doubted, for instance, the Existence of the Deity, that he made the World, and govern’d it by his Providence; that the most acceptable Service of God was the doing Good to Man; that our Souls are immortal; and that all Crime will be punished and Virtue rewarded either here or here-after; these I esteem’d the Essentials of every Religion, tho’ with different degrees of Respect as I found them more or less mix’d with other Articles which without any Tendency to inspire, promote or conform Morality, serv’d principally to divide us and make us unfriendly to one another (sic).7 Franklin’s belief in “serving God” by “doing Good to Man” motivated him to create a Club called the Junto. Franklin stated that he created a “Club for Mutual Improvement” and rules to ensure each member would produce “Queries on any Point of Morals, Politics, and Natural Philosophy, to be discuss’d by the Company, and once in three Months produce and read an Essay of his own Writing on any Subject he pleased (sic).”8 Philosophical Societies such as this will contribute to the spread of enlightenment thought in America as Franklin founded or contributed to several other clubs and societies devoted to enlightened debate. Franklin’s devotion to diffusion of enlightenment thought prompted him to create the first subscription library in North America, The Library Company of Philadelphia.9 It is evident why Gordon Wood claims Franklin is “the American Enlightenment personified.”10 It is interesting that 7 Franklin spreads enlightenment thought along with a morality not directly tied to any one religious institution. To clarify, Franklin was a theist who was not tied to any one specific religious institution. He worked alongside Anglicans, Presbyterians, Baptists, and Moravians to ensure no religious sect would dominate the University of Philadelphia, which was chartered in 1753 in a colony dominated by Quakers. Franklin’s devotion to moral teachings prompted his aspiration to create a book titled, The Art of Virtue, containing his personal improvement plan. This pipe dream is further testament to his devotion to introspection and self-improvement and he included a draft of it in his Autobiography. Franklin identifies and explains thirteen virtues he wishes to follow while providing a grid to track his weekly progress toward meeting these virtuous goals. Franklin lists Temperance, Silence, Order, Resolution, Frugality, Industry, Sincerity, Justice, Moderation, Cleanliness, Tranquility, Chastity, and Humility as the virtues to strive for. He also identifies goals in meeting each one, e.g., under Industry, Franklin writes, “Lose no time. Be always employ’d in something useful. Cut off all unnecessary Actions (sic).”11 Contemporary Americans stand to benefit from personal and professional improvement plans similar in nature to the one Franklin created. I plan on having students list four areas in their life that need improvement, in order to generate a chart similar to the one Franklin uses so they too may track their progress. Here is an example of areas students at Milford High School could improve upon, taken directly from Franklin’s list: 1. Silence. Speak not but when you may benefit others or yourself. Avoid trifling conversation. 2. Resolution. Resolve to perform what you ought. Perform without fail what you resolve. 8 3. Sincerity. Use no harmful Deceit. Think innocently and justly; and if you speak, speak accordingly. 4. Justice Wrong none, by doing Injuries or omitting the Benefits that are your Duty. 5. Tranquility Be not disturbed by Trifles, or at accidents common or unavoidable.12 Introspection of self-determined areas of improvement should prove to be an interesting class assignment and lead to a lively class discussion. In order to stress Franklin’s belief in introspection and self-improvement to the youths of today I have attached a worksheet at the conclusion of the paper. Franklin’s strict adherence to living a moral and virtuous life led him to become one of America’s greatest assets. Many of Franklin’s greatest achievements were actions designed to “do good to man.” In his native Pennsylvania, after achieving tremendous wealth through his printing company, Franklin served as a member of Pennsylvania’s General Assembly and became a prominent politician. Franklin’s work as a politician and philosopher allowed him to serve the public as he devoted all of his energy to helping his fellow man. Franklin’s work with electricity and efforts to protect and serve the community reflect this mentality. Franklin’s electrical experiments led him to create the lightning rod, which greatly reduced the risk of fire associated with lightning strikes. Franklin will help establish Philadelphia’s city watch, a fire company, and even serve as Colonel in the Pennsylvania militia during the French and Indian War. Franklin’s public service eventually led to his rise as a prominent politician during the French and Indian War and during the American Revolution. True to Franklin’s nature he will attempt throughout both conflicts to promote unity among his brethren at great personal costs. 9 In 1754, Franklin’s Albany Plan of Union was the first plan calling for unification of the colonies, well before the Continental Congress was formed. Franklin argues that had his plan been adopted the Revolutionary war may have been averted. Franklin states: I am still of the Opinion it would have been happy for both Sides of the Water if it had been adopted. The Colonies so united would have been sufficiently strong to have defended themselves; there would then have been no need of Troops from England; of course the subsequent Pretence for Taxing America, and the bloody Contest it occasioned, would have been avoided. But such Mistakes are not new; History I full of the Errors of states and Princes (sic).13 Following the French and Indian War, Franklin will travel to England where is eventually appointed as a colonial agent for Georgia, New Jersey, and eventually Massachusetts. While in England Franklin became the spokesman for the colonial argument against the Tea Act and other British taxes while attempting to promote unity between the colonies and Great Britain. For a time Franklin was confident that the issues between the colonies and mother country could be solved, but he is radicalized after becoming a scapegoat for colonial discontent and humiliated by the Privy Council following the Boston Tea Party in 1774. Franklin is loyal to a fault even after being humiliated and generously offers to compensate the British for the cost of the destroyed tea. After his humiliation in Britain, Franklin will return home a die-hard patriot, his dreams of unity shattered. Unfortunately, due to his time abroad and his son, William Franklin’s refusal to support the independence movement, revolutionaries such as Richard Henry Lee branded Franklin an Anglophile and potential British spy. Oddly, Franklin became a political pariah in pre and post revolution America as he is publicly chastised by men such as, Richard Henry Lee who during the revolution wanted him removed as Ambassador to France. Soon after, John Adams and the Federalist Party accused Franklin of being a Francophile after signing the Treaty of Paris and during the ensuing French 10 Revolution. Franklin is given little credit immediately following the American Revolution and upon his death he is eulogized more passionately in France than in the United States, as Senate did nothing after receiving word of his death. According to Gordon Wood this was due to John Adam’s jealousy of Franklin’s many successes. John Adams stated in a jealous rant: The history of our Revolution will be one continued Lye from one end to the other. The essence of the whole will be that Dr. Franklin’s electrical rod, smote the Earth and out sprung General Washington. That Franklin electrified him with his rod--and thence forward these two conducted all the Policy, Negotiations, Legislatures and War (sic).14 This rant is surprising since both Adams and Franklin served in France negotiating the Treaty of Paris in 1783. In a sense, Franklin’s quest for moral perfection was complete as he now achieved the humble status of his role models i.e., Socrates and Christ who were both martyred for their efforts to improve society. It would not be until years later that Franklin’s contributions to the world developed universal appeal as he became a model of advancement based on merit and champion of the working-class. 11 Name: Directions: Benjamin Franklin planned on writing The Art of Virtue to educate men on proper moral behavior as well as to keep his own moral values in check. Read Benjamin Franklin’s list of thirteen virtues, then develop your own list of qualities you wish to improve in your own life. Try to come up with at least four things you could improve upon. See the example below. 1. Industry “Lose no time. Be always employ’d in something useful. Cut off all unnecessary Actions.” 2. 3. 4. 5. Use the grid below to check your weekly progress. See example below. Guide to self-improvement based on Benjamin Franklin’s The Art of Virtue * Success 1. Industry 2. 3. 4. 5. Sunday Monday * Completed homework without distraction Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 12 Bibliography Franklin, Benjamin. The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin. Edited by Leonard W. Labaree et al. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1964. Wood, Gordon. The Americanization of Benjamin Franklin. New York: The Penguin Press, 2004. Notes 1 Benjamin Franklin, The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1964), 2 Gordon S. Wood, The Americanization of Benjamin Franklin (New York: The Penguin Press, 2004), 200. 3 Wood, The Americanization of Benjamin Franklin, 202. 4 Ibid., 203 5 Franklin, The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin, 44. 43. 6 Ibid., 150. 7 Ibid., 146. 8 Ibid., 116-117. 9 Ibid., 130. 10 Wood, The Americanization of Benjamin Franklin, 180. 11 Franklin, The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin, 149. 12 Ibid., 149-150 13 14 Ibid., 211. Wood, The Americanization of Benjamin Franklin, 232.