An Uncommon Library - Johns Hopkins Gazette, September 2012

advertisement

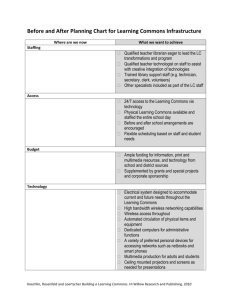

Reprinted with permission from the Johns Hopkins University Gazette An Uncommon Library By Joe Sugarman / Photos by Will Kirk T he free smoothie machine didn’t make the cut. Nor did the coin-operated massage chairs or the “napping pods.” But most of the other (more practical) suggestions contributed by students for the Brody Learning Commons were integrated into its final design—and that was one of the primary goals. “We knew it was the students who should be driving this from day one,” says Winston Tabb, Sheridan Dean of University Libraries and Museums. Visitors to the Homewood campus’s Brody Learning Commons, named in honor of the university’s 13th president, William R. Brody, and his wife, Wendy, will be able to see student input everywhere they look, from the funky foam chairs shaped like balls on the building’s ground level to the 75-seat Daily Grind café with its ample plugs for laptops and electronics. But the number one request from students who filled out online surveys? Natural light, says Tabb. Architects from Shepley Bulfinch Richardson & Abbott responded by designing a building seemingly made of mostly windows and skylights. Enter through the Metro-like metal gates from the Keyser Quad and you’re immediately struck by how bright things are. “There aren’t too many spaces where you don’t get natural light,” says Brian Shields, communications and marketing manager for the Sheridan Libraries and Left: The Keyser Quadrangle entrance to the Brody Learning Commons leads visitors directly into the 75-seat Daily Grind café, which is equipped with ample plugs for laptops and electronics. Above: Natural light fills the Schnydman Atrium, where chairs and whiteboards on wheels allow students to adapt the space to their needs. Looking onto the room from above are glass-walled group study rooms. University Museums, who stands in as tour guide on a recent visit. We head into one of the building’s 16 group study rooms—a fishbowllike affair, with a floor-to-ceiling glass wall trimmed in eye-popping blue, that overlooks the building’s Schnydman Atrium. Students or faculty can reserve online any of the study rooms, and all boast short-throw projectors, reconfigurable seating and walls, and glass windows that double as erasable whiteboards. Our next stop is the quiet reading room, a light-filled space with soaring ceiling and seating for 100. It’s a favorite of Tabb’s. “Previously, the university didn’t have a true reading room, a quiet place where people go to study, like at many other universities,” says Tabb, who notes that he’s been looking forward to an expansion of the Eisenhower Library since his arrival at Johns Hopkins in 2002. “Walking into the room is so inspirational.” Artist Mark Dion’s installation, An Archaeology of Knowledge, a giant “cabinet of wonders,” stretches from floor to ceiling and contains ephemera from across the university— microscopes, globes, old chemistry cabinets, and much more— behind glass and in drawers that can be opened by visitors. “We knew we wanted to have art, and at first you think of painting or sculpture,” says Tabb. “But this is a kind of art that really draws on so many subjects, reflecting the ways that people learn. I can’t wait to go there and plow through all the drawers.” Shields and I walk past a bank of lockers—each has an outlet inside to recharge electronics—and down to the M-Level, home to the Department of Special Collections. We poke our heads into the Macksey Seminar Room, named in honor of Humanities Professor Emeritus Richard Macksey and his late wife, Catherine. Macksey hosted generations of students in his home for seminars and has bequeathed his more than 70,000 volumes to the university. A set of doors and windows on each floor connects BLC with the Eisenhower Library, creating a uniform space. “That’s one of the things I really like,” says Tabb. “The ability to see through the old and into the new. We really needed to have two buildings operating as one library.” The B-Level features another entrance/exit with steps made from repurposed marble from Gilman and Shriver halls. Shields points out a 12-by-7-foot bank of a dozen linked monitors, a “visualization wall,” a joint project of the Sheridan Libraries and the Whiting School’s Department of Computer Science, that will allow researchers to develop a better sense of how humans interact with computers. The rest of the main floor is meant to be flexible, as students will be able to configure chairs and whiteboards on wheels, creating impromptu study areas—something Tabb can’t wait to see in action. “I’m sure students will use it in ways we can’t imagine,” he says. “When I see the students owning the building, using it in ways they want, I’ll be extremely pleased.” g Brody Learning Commons by the Numbers Top: Artist Mark Dion’s giant installation, An Archaeology of Knowledge, invites visitors to explore and handle ephemera collected from across the university. Bottom: An interior balcony/walkway that overlooks the atrium and connects the Brody Learning Commons to the Eisenhower Library, left. 26 Johns Hopkins University 42,000 square feet 16 flexible group study rooms 6 teaching and seminar rooms 100-seat quiet reading room 75-seat café and atrium 500 additional seats 84 square feet size of electronic “visualization wall” 7 online votes supporting “bean bag chairs” 1st new-construction project at Homewood to pursue LEED silver certification $32.4 million cost of construction, funded entirely through private donations