THE WORLD ISLAND: EURASIAN GEOPOLITICS AND THE FATE

advertisement

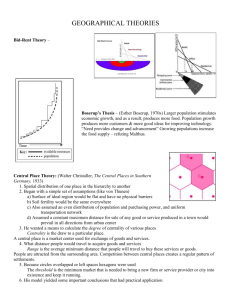

NIHAT ÇELIK IEW V E KR O BO 156 THE WORLD ISLAND: EURASIAN GEOPOLITICS AND THE FATE OF THE WEST NIHAT ÇELIK Kadir Has Üniversitesi An undeclared war has already begun between those powers of Eurasia and the West; control of the mostly unexploited energy and mineral sources of Eurasia. WHETHER AND HOW, TO ENGAGE IN EURASIA IS THEREFORE THE WEST’S EXISTENTIAL QUESTION. new zones of influence by pressurizing the smaller Eurasian states in order to eradicate Western influence. However, the typology of this confrontation is different from the Cold War era superpower rivalry. Rather than blunt military force or the threat thereof, the tools in play are economic leverage and political subterfuge. Signaling a return to the age of geopolitics, the author assesses the main geopolitical theories and doctrines such as Alfred T. Mahan’s Sea Power Theory, Sir Halford Mackinder’s Heartland Theory, Nicholas J. Spykman’s Rimland Theory, Josef Pilsudski’s PrometheismIntermarum Concept, and George Kennan’s Containment Theory from a historical perspective. Petersen does far more than merely review these historical theories and doctrines; he provides a useful analysis of their current relevance in line with technological developments and political, economic, demographic and security trends. He amalgamates these theories to substantiate already proven geopolitical principles, presenting concrete policy models to the decision-makers of the Euro-Atlantic Community and its allies in Eurasia. 157 HAZAR RAPORU, SUMMER 2013 The World Island is an attempt to increase awareness of Eurasia’s geopolitical importance in the minds of Western decision-makers, politicians, academics and public. Petersen underlines Eurasia’s crucial role in the survival of the Western democracies in the context of the ensuing confrontation with autocratic regimes of Eurasia, to use the author’s terminology, the ‘Revanchist Bear’ (Russia) and the ‘Rising Dragon’ (China). In stark contrast to the ‘end of history’ or ‘end of geopolitics’ theses that emerged in the over-optimistic environment of the post-Cold War era, the author takes a realist, straightforward approach, and issues a clear warning about the possible global implications of failed Western involvement in Eurasia, in relation to the future of democracy and freedom. The author asserts that an undeclared war has already begun between those powers of Eurasia and the West; control of the mostly unexploited energy and mineral sources of Eurasia and the fate of the Western regimes will be determined in the Eurasian landmass by their inaction or actions. Russia and China are trying to form NIHAT ÇELIK 158 It is Sir Halford Mackinder’s Heartland Theory that primarily shapes the author’s approach. He considers geography as a constant in strategy formulation, while other factors like population, production and military power are subject to change, and as such these factors are considered as variables. Through an in-depth analysis of Eurasian history, Mackinder showed that starting with the Huns, westward invasions have always been successful. In contrast, eastward invasions have been unsuccessful, as Alexander the Great, Napoleon Bonaparte and Adolf Hitler proved. The main reason of this failure lies in the geography: the ‘Pivot Area’ or ‘Heartland’, starting IN THIS CLIMATE THERE IS A DANGER THAT CHINA MAY EMERGE AS AN ALTERNATIVE SOURCE OF ECONOMIC SUSTENANCE FOR MUCH OF THE DEVELOPING WORLD. at the isthmus between the Baltic and Black Sea and reaching almost to the Pacific Ocean in the east, is the greatest natural fortress on the world. It is surrounded by the Arctic Sea in the north, by deserts and mountain ranges on other sides. Contrary to Admiral Alfred Mahan’s Sea Power Theory, which suggested that a naval power can gain international influence by controlling the important choke-points and naval bases in the oceans. Mackinder showed that the Heartland is inaccessible by any sea power, while a land power established at the Heartland can command the oceans by controlling the World Island (‘the Old World’ consist- ing of Asia, Europe and Africa, the mega-continent surrounded by interconnected oceans). Thus Mackinder formulated his famous dictum: “Who rules Eastern Europe commands the Heartland; Who rules the Heartland commands the World-Island; Who rules the WorldIsland commands the World.” Mackinder’s theory was supported by the political developments in the following decades, forming formed the backbone of Karl Haushofer’s Lebensraum Theory and Nazi political designs. Containment Policy of George Kennan was also built upon Mackinder’s solid basis, it aimed at keeping the Soviet Union out of the Mackinder’s ‘Inner Crescent’ or Nicholas Spykman’s ‘Rimland’. However, the author suggests that Containment Policy is simply not enough to cope with the greater threats of today. It can only provide a minimum standard for what the West must do in order to sustain its position. Thus Petersen brings to the fore the interwar era Prometheism-Intermarum (Between the Seas) Concept developed by Polish President Joseph Pilsudski, which envisaged a confederation of states in the area between the Baltic and Black Sea, ranging from Poland to Azerbaijan, as a counterweight to Russia. The author provides a valuable insight into the current state of affairs in Eurasia ranging from regional organizations dominated by Russia and China such as the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) and Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), energy and rich countries with the purpose of establishing a monopoly over the sources and energy projects of the future, as a political tool. China, feeling insecure due to the energy and other mineral sources it needs to sustain its high growth-rate in the following decades, is working with Russia to ‘plunder’ the Eurasian states. It is no surprise that China is turning wealth into might and power projection capability, as “THE CORRESPONDING REALITY IS THAT UKRAINE IS NOT ESSENTIAL FOR WESTERN INTEGRATION TO CONTINUE IN EURASIA.” shown by its huge naval armament program. Pursuant to this, the author analyzes the strengths and weaknesses of each Eurasian country situated between Russia and China by providing statistical data on their economies, populations, and political orientation. Then the author starts building his Twenty-First Century Geopolitical Strategy for Eurasia (21 CGSE), citing and where necessary updating the geopolitical theories mentioned above and current political along with economic trends. He puts forward policy prescriptions for decision-makers, requiring genuine commitment and long-term dedication. He suggests ‘the Three I’s’ policy: Independence, Integration, Institutions. In his view, the first necessary step is to decrease the level of dependency of Eurasian states on Russia and China by providing policy alternatives through the use of political, economic and cultural tools. Secondly, through 159 HAZAR RAPORU, SUMMER 2013 transportation projects to armament projects. The Russia-Georgia War of 2008 was a turning-point in the recent history of the region, changing all political calculations and sending a clear message to countries Western-oriented countries in Eurasia that were promoting universal values like democracy, freedom and free-market economy. The author argues that notwithstanding problems in their bilateral relations and different regional designs, Russia and China are acting together to eliminate Western influence in Eurasia. This is evident through their intention to transform the CSTO into the NATO of Eurasia by organizing joint military exercises and requesting a UN mandate for peace-keeping missions in the region. It is clear that the main reason for this struggle is to gain control of key energy sources and the transit corridors of energy projects. While Russia is itself resource rich when it comes to energy, it still seeks to control other energy NIHAT ÇELIK THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY GEOPOLITICAL STRATEGY FOR EURASIA ADVOCATES FAR GREATER WESTERN INVOLVEMENT IN EURASIA THAN NEVER BEFORE. 160 Russian President Putin and Chinese President Jintao EU involvement and transportation projects such as the Northern Distribution Network and the Modern Silk Road, Trans-Eurasian trade should be revived. These would be faster and more cost-effective in comparison to the trans-oceanic trade. However, the draconian customs regimes of the Eurasian countries undermine the development of these trade routes which will integrate the region to the world and foster trade, development, stability and regional integration while breaking up Russian-Chinese monopoly. First of all, the customs re- gimes should be changed to encourage trade. In addition, reasonable investment in infrastructure is necessary, and should be provided by the U.S. at the initial stages. Thirdly, by supporting institution-building efforts and promoting universal values such as good-governance and rule of law which will help attract foreign direct investment, Western institutions like the EU, NATO, OSCE and Council of Europe will play a crucial role. However, in order to fulfill that role, those institutions should undergo reforms and develop more effective mechanisms for their active involvement in Eurasia. The author pays close attention to Euro-Atlantic cohesion. He argues that if members of the Euro-Atlantic community choose to act alone, as Germany did with Russia for the Nordstream Pipeline Project, this will only benefit the autocratic and mercantilist powers of Eurasia. In conclusion, Alexandros Petersen’s work provides significant and important insights into Eurasian politics, offering an in-depth and wide-ranging analysis of recent developments and trends in the region while providing a projection for the future, underpinned by concrete policy options. It is necessary to read Petersen’s book to understand the dynamics of the ‘New Great Game’. HAZAR RAPORU, SUMMER 2013 161