Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes xxx (2014) xxx–xxx

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/obhdp

Responses to normative and norm-violating behavior: Culture, job

mobility, and social inclusion and exclusion

Jennifer Whitson a,⇑, Cynthia S. Wang b, Joongseo Kim b, Jiyin Cao c, Alex Scrimpshire b

a

The University of Texas at Austin, Department of Management, McCombs School of Business, Austin, TX 78705, United States

Oklahoma State University, Department of Management, Spears School of Business, Stillwater, OK 74078, United States

c

Stony Brook University, Department of Management, College of Business, Stony Brook, NY 11794, United States

b

a r t i c l e

i n f o

Article history:

Received 13 January 2013

Accepted 11 August 2014

Available online xxxx

Accepted by Michael Morris, Ying-yi Hong

and Chi-yue Chiu

Keywords:

Culture

Job mobility

Social inclusion

Social exclusion

a b s t r a c t

Research has demonstrated the effects of culture and mobility on the utilization of monetary rewards and

punishments in response to norm-related behaviors (e.g., honesty and dishonesty), but less is known

about their effects on the utilization of social inclusion and exclusion. Three experiments found that individuals in high job mobility contexts were more likely to exclude dishonest actors than those in low

mobility contexts; job mobility did not affect the level of social inclusion. Experiment 1 demonstrated

cultural differences in the utilization of social inclusion/exclusion versus monetary rewards/punishments, with perceived job mobility as an underlying mechanism. Experiment 2 provided a behavioral

measure of social inclusion/exclusion. Experiment 3 manipulated job mobility and found that the perceived difficulty of social exclusion mediated the relationship between job mobility and social exclusion.

This paper illustrates critical boundary conditions for past findings and provides insight into responses to

norm-related behavior across different cultures.

Ó 2014 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Introduction

When employees uphold or break norms, organizations often

have formal systems of responding, and research has shown that

rewards and punishments are critical in creating environments that

encourage good and deter bad behavior (e.g., Chen, 2012; Fuster &

Meier, 2010; Podsakoff, Bommer, Podsakoff, & MacKenzie, 2006;

Wayne, Shore, Bommer, & Tetrick, 2002). Practically, rewards and

punishments are effective in altering behavior (Kazdin, 2001), and

organizations design financial incentive systems (e.g., performance

bonus systems; financial sanctions) to reinforce positive norms and

to increase employee motivation. Research has demonstrated the

prominent use of both monetary rewards (Wang, Galinsky, &

Murnighan, 2009) and punishments (Gray, Ward, & Norton,

2012), and a meta-analysis established that both increase cooperation in social dilemmas (for a review, see Balliet, Mulder, & Van

Lange, 2011). However, whereas monetary rewards and punishments offer clear tools for managers to respond to employees

who uphold or break norms, they are less widely available to most

individuals. For example, coworkers generally cannot provide

financial bonuses and sanctions to peers.

⇑ Corresponding author.

In this paper, rather than focusing on monetary responses to

normative (e.g., honest) and norm-breaking (e.g., dishonest)

behavior, we draw attention to a form of response widely available

to organizational members: social inclusion (i.e., the act of including

someone in interpersonal relationships) and social exclusion (i.e.,

the act of excluding someone from interpersonal relationships;

Abrams, Hogg, & Marques, 2005). Decisions to include normupholders or exclude norm-violators likely see more widespread

use, because they can be made by almost everyone in social, group,

or organizational contexts (Abrams et al., 2005). Importantly, our

proposal moves beyond monetary responses to normative and

norm-breaking behavior, delineating them from other responses,

particularly social inclusion and exclusion.

To date, little is known about how individuals from different

cultural contexts choose to socially include and exclude others.

We posit that the usage of these norm-related responses will differ

across cultural contexts and that a critical socioecological factor

driving these differences is the level of job mobility, i.e., the degree

to which individuals can change jobs and professions within a

given environment (Chen, Chiu, & Chan, 2009).

The current research makes important contributions to theory

on culture and responses to norm-related behaviors by lending

insight into the crucial function that job mobility plays in different

responses within and between cultures. This is theoretically

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2014.08.001

0749-5978/Ó 2014 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Please cite this article in press as: Whitson, J., et al. Responses to normative and norm-violating behavior: Culture, job mobility, and social inclusion and

exclusion. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes (2014), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2014.08.001

2

J. Whitson et al. / Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes xxx (2014) xxx–xxx

compelling because social inclusion and exclusion and monetary

incentives may be utilized very differently, depending on the

socioecological context in which they occur. We next provide an

overview of the effects of social inclusion and exclusion. We then

theorize how perceptions and experiences of job mobility may lead

to differences in social inclusion and exclusion within and between

cultures.

The effects of social inclusion and exclusion

The need to belong is a fundamental human motivation

(Baumeister & Leary, 1995) and being accepted as a member of a

group is an integral human need (Maslow, 1968; Ryan & Deci,

2000). Social inclusion leads to a multitude of emotional and

health benefits. For example, when people’s need to belong was

satisfied, they exhibited higher intrinsic motivation (Ryan & Deci,

2000), reported greater well-being (Tay & Diener, 2011), and experienced increased self-esteem (Heppner et al., 2008). These effects

also occur at societal levels: not only did individuals with more and

higher-quality relationships have higher self-esteem, but countries

with inhabitants who regularly interacted with friends had higher

nationwide self-esteem levels (Denissen, Penke, Schmitt, & van

Aken, 2008).

Individuals also can socially exclude others. William James once

noted that being excluded is an extremely aversive experience,

writing, ‘‘No more fiendish punishment could be devised, were

such a thing physically possible, than that one should be turned

loose in society and remain absolutely unnoticed by all the members thereof’’ (James, 1890, p. 293). In fact, the experience of exclusion can be so intense that socially excluded individuals exhibit

neural activity similar to that caused by physical pain

(Eisenberger, Lieberman, & Williams, 2003; MacDonald & Leary,

2005). Social exclusion engenders anxiety (Baumeister & Tice,

1990; Leary, 1990), loneliness (e.g., Peplau & Perlman, 1982), anger

(e.g., Williams, Shore, & Grahe, 1998), impaired self-regulation

(Baumeister, DeWall, Ciarocco, & Twenge, 2005), and self-defeating

behavior (e.g., Twenge, Catanese, & Baumeister, 2002).

Given the powerful psychological and behavioral ramifications,

social inclusion and exclusion serve as effective ways to enforce

normative behavior. For example, including helpful individuals

and excluding unhelpful individuals shapes group socialization

and norms over time (Levine, Moreland, & Hausmann, 2005). Congruently, the threat of ostracism is considered a fundamental

mechanism of establishing a norm (Ouwerkerk, Kerr, Gallucci, &

Van Lange, 2005) and actual ostracism has been shown to promote

cooperation in groups (Feinberg, Willer, & Schultz, 2014). These

findings suggest these strategies can be effective in promoting normative behavior, thus, influences on their utilization are crucial

topics of study. Despite these findings, there is a paucity of

research about their utilization across contexts with different levels of job mobility. In the next section, we discuss why culture and

job mobility might hold such an influential position in the use of

social inclusion and exclusion.

Culture and job mobility

Mobility is a socioecological construct (Oishi & Graham, 2010)

that takes into account the macro-environment (e.g., the structural

characteristics of cities; the economic and political landscape of a

community) and its psychological and behavioral ramifications.

Mobility has been studied in the context of residential mobility

(the degree to which people can change their residence within a

given environment; Oishi, 2010), relational mobility (the degree

to which people can change relationship partners within a given

environment; Schug, Yuki, Horikawa, & Takemura, 2009) and job

mobility (the degree to which people can change jobs and professions within a given environment; Chen et al., 2009; Yuki et al.,

2007).

Recent research suggests that mobility is deeply tied to many

features of a given culture. For example, residential mobility alters

the qualities preferred in associates and friends (Lun, Oishi, &

Tenney, 2012) and influences self-construals (Oishi, Lun, &

Sherman, 2007). Cultural differences in relational mobility affect

the level of similarity between friends (Schug et al., 2009) and

monetary reward and punishment decisions (Wang & Leung,

2010). Finally, cultural differences in job mobility are associated

with different worldviews (Chen et al., 2009), with individuals in

high mobility contexts less likely to endorse a belief in a fixed

world.

Our reasons for focusing on job mobility are twofold. First, job

mobility has important implications for interpersonal interactions

within organizations. Second, mobility is a critical driver of cultural

differences, and perceived job mobility in particular influences cultural patterns of judgment and behavior (Chiu & Chen, 2004;

Stryker, 2007). Phenomena that occur at these societal levels are

powerful predictors of cross-cultural difference (Bahns, Pickett, &

Crandall, 2012; Chen et al., 2009; Falk, Heine, Yuki, & Takemura,

2009; Heine & Renshaw, 2002; Schug et al., 2009; Schug, Yuki, &

Maddux, 2010; Yuki et al., 2007), and therefore valuable factors

to be aware of in the life of an organization. Importantly, the frequency that employees change jobs and professions throughout

their work careers varies significantly by country (Borghans &

Golsteyn, 2012). For example, Americans change jobs quite frequently, with the average American holding approximately ten

jobs over a lifetime (Bialik, 2010; Topel & Ward, 1992). In an 11country comparison (Borghans & Golsteyn, 2012), college graduates in the United States changed jobs most often, with only 19%

of graduates still holding their first job after three years. In contrast, the Korean Employment Information Service (2009) reports

that the average Korean holds only 4.1 jobs over a lifetime. Job

mobility can also differ within countries (Chen et al., 2009); for

example, the 2007–2009 Great Recession resulted in a significant

decrease in job mobility in multiple countries (Meriküll, 2011;

Moscarini & Postel-Vinay, 2013). We argue that the employment

of social inclusion and exclusion is influenced by job mobility.

Culture, job mobility, and the utilization of social inclusion and

exclusion

Recent research on cultural differences in monetary responses

to norm-related behaviors suggests that mobility plays a crucial

role. Mobility critically influenced monetary responses, such that,

Americans (who tend to be higher in job and relational mobility)

rewarded honest actors more and punished dishonest actors less,

than East Asians (Wang & Leung, 2010; Wang, Leung, See, & Gao,

2011). The same effects were found when job mobility was manipulated rather than measured (Wang et al., 2011).

The authors posited that the strength of ties drove these effects

(Wang & Leung, 2010; Wang et al., 2011). The looser networks in

high mobility societies increased rewards as individuals attempted

to strengthen ties with more relationally-distant honest others. In

contrast, the tighter-knit networks generally found in low mobility

societies increased feelings of obligation to maintain order via punishment. These mobility-driven differences in the strength of ties

may also influence choices to include and exclude.

Specifically, we predict that job mobility, with its critical function in determining strength of ties, will influence how individuals

choose to socially include and exclude, with these effects dramatically differing from monetary responses. Unlike studies involving

monetary incentives, social inclusion and exclusion are inherently

Please cite this article in press as: Whitson, J., et al. Responses to normative and norm-violating behavior: Culture, job mobility, and social inclusion and

exclusion. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes (2014), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2014.08.001

J. Whitson et al. / Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes xxx (2014) xxx–xxx

tied to the contextual affordances of mobility. As we discuss below,

the ease with which one’s context affords the maintenance and

deepening of ties will influence social inclusion in response to normative behaviors. Further, the ease with which one’s context

affords the weakening of ties will influence social exclusion in

response to norm-violating behaviors.

Social inclusion can be about forming, maintaining, or strengthening ties with an individual. Congruently, social exclusion can be

about weakening or dissolving ties with an individual (Abrams

et al., 2005; Baumeister & Leary, 1995). Within organizations,

employees rarely have control over who is introduced into or

ejected from their social contexts (i.e., hired or fired). As a result,

their choices to socially include will be based largely around decisions to maintain and deepen (rather than form) ties with individuals who share the same context as they do, whereas choices to

socially exclude will be based on decisions to weaken (rather than

dissolve) ties. Due to our emphasis on organizational contexts, this

paper therefore focuses on the maintenance, strengthening, and

weakening of ties.

In terms of social inclusion, low mobility environments provide

affordances that make it easier to maintain ties. Relationships with

others require communication and contact with one another (Hays,

1985). It may be easier to maintain ties in low mobility contexts

because the stable, dense networks in those contexts will help to

sustain them (Bian & Ang, 1997). Indeed, relationships in low relational mobility societies tend to be more stable and resilient to

shocks or neglect (Wiseman, 1986; Yuki & Schug, 2012). Moreover,

individuals in low mobility contexts may be motivated to deepen

existing ties, because those ties last longer and serve multiple functions (Lun et al., 2012; Oishi & Kesebir, 2012). Research supports

this proposition, as individuals in low residential mobility contexts

feel less lonely (Oishi et al., 2013), and have deeper relationships

with others that span multiple activities and preferences (Oishi,

2010). This suggests that individuals in an environment with low

job mobility will be more likely to have interconnected and stable

networks, making ties much easier to maintain and deepen (Dess &

Shaw, 2001; Lewis, Belliveau, Herndon, & Keller, 2007), therefore

increasing social inclusion. In a low-turnover organization, one

can imagine coworkers will come to know each other’s preferences

and find it easier to invite each other to events. However, in a highturnover organization, the sparse and volatile nature of interpersonal networks would make it more difficult to do so.

Thus, because individuals in low mobility contexts perceive

maintaining and deepening bonds with others as easier, we expect

they will be more likely to socially include honest actors than individuals in high mobility contexts. Moreover, we test cultural differences in two countries: the United States and South Korea. We

speculate that Koreans are more likely than Americans to use social

inclusion, because South Korea has a lower level of job mobility

than the United States.

Hypothesis 1, Social Inclusion (H1SI): Individuals in low job

mobility contexts are more likely than individuals in high job

mobility contexts to socially include an honest actor.

Hypothesis 2, Social Inclusion (H2SI): South Koreans perceive

themselves as possessing lower job mobility than Americans,

which translates into increased social inclusion.

The contextual affordances of high job mobility allow individuals to more easily weaken bonds with norm-violators, and social

exclusion is an opportune method to punish them and clean up

the social environment simultaneously. Conversely, low job

3

mobility contexts provide fewer affordances for weakening undesirable relationships, making social exclusion more difficult to

employ in response to dishonest, norm-violating actors. Indeed,

research suggests that Americans express a greater desire to avoid

dishonest actors than do East Asians (Wang & Leung, 2010), implying that social exclusion may be a more prominent option in high

mobility contexts than in low mobility contexts.

In essence, social exclusion cannot be accomplished when one

is continuously brought into contact with a norm-violator, and it

is more feasible to exclude a norm-violator in a high mobility

environment where social networks are less dense. For example,

an employee in a low-turnover organization who wishes to

exclude a dishonest actor from social events will have a hard

time of it, as that actor is likely to have ties with many other

individuals in the organization, and thus their exclusion would

require the coordination of many. Conversely, exclusion would

be easier in the sparser networks of a high-turnover organization, and indeed, social exclusion is more likely to be used in situations when the cost is low, for example, when there is less

interdependence between individuals (Robinson, O’Reilly, &

Wang, 2013). Thus, we suggest individuals in high job mobility

environments will exclude more than those in low job mobility

environments.

We also test whether cultural differences exist between the

United States and South Korea. We predict that Americans are

more likely than South Koreans to use social exclusion as a

response to dishonest actors, because the United States has a

higher level of job mobility than South Korea.

Hypothesis 1, Social Exclusion (H1SE): Individuals in high job

mobility contexts are more likely than individuals in low job

mobility contexts to socially exclude a dishonest actor.

Hypothesis 2, Social Exclusion (H2SE): Americans perceive themselves to possess higher job mobility than South Koreans, which

translates into increased social exclusion.

Overview of experiments

Three experiments test the effects of job mobility on social

inclusion and exclusion. Experiment 1 examines how social

inclusion and exclusion, as well as monetary reward and punishment, are employed by Americans (high job mobility) and South

Koreans (low job mobility). We test perceived job mobility as

the mechanism underlying our proposed effects. Experiment 2

measures perceived job mobility and utilizes a behavioral measure of social inclusion and exclusion. Experiment 3 manipulates

perceived job mobility and tests whether social inclusion and

exclusion decisions are influenced by the perceived difficulty of

doing so.

Experiment 1: Culture, job mobility, and responses to honesty

and deception

Experiment 1 measured the perceived job mobility (Chen et al.,

2009) of Americans (high job mobility) and South Koreans (low job

mobility). We compared the effects of national culture and perceived job mobility on two different strategies of norm enforcement: monetary reward or punishment (using the measure from

Wang et al., 2009) and social inclusion or exclusion. We included

monetary responses to replicate previous findings (Wang &

Leung, 2010; Wang et al., 2011) and to provide comparison points

for the social inclusion and exclusion findings.

Please cite this article in press as: Whitson, J., et al. Responses to normative and norm-violating behavior: Culture, job mobility, and social inclusion and

exclusion. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes (2014), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2014.08.001

4

J. Whitson et al. / Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes xxx (2014) xxx–xxx

Table 1

Descriptive statistics and variable inter-correlations, Experiment 1.

Variables

Mean

SD

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

.34

.51

.19

3.60

3.78

22.05

.62

.47

.50

2.29

1.86

1.35

3.64

.49

1.00

.03

.51**

.00

.34**

.42**

.08

1.00

.03

.07

.17*

.01

.05

1.00

.01

.09

.28**

.02

1.00

.06

.02

.06

1.00

.13

.05

1.00

.05

1.00

Culture (0 = US; 1 = South Korea)

Behavior (0 = Honesty; 1 = Dishonesty)

Job mobility

Monetary response

Social inclusion or exclusion

Age

Sex (0 = Male; 1 = Female)

Note: N = 221.

*

Correlation is significant at p 6 .05.

**

Correlation is significant at p 6 .01.

Method

Participants and design.1 Two-hundred and twenty one undergraduate students from a US southwestern university and a South

Korean university responded to a scenario as part of a class exercise.

The American sample included 146 students (94 females and 52

males; 70 Caucasians, 48 Asians, 19 Hispanics, 6 African Americans,

and 3 other races; mean age = 20.95, SD = 1.82, range = 19–31) and

the South Korean sample included 75 students (42 females and 33

males; all Asian; mean age = 24.19, SD = 5.10, range = 18–56). The

design was a 2 (behavior: honest, dishonest) 2 (culture: American,

Korean) between-participants design (see Table 1 for descriptive statistics and correlation matrix).

Procedure. Following Wang et al. (2009), American and Korean

participants received scenarios in their respective national languages (English in the US and Korean in South Korea) in which

an actor was honest or dishonest. The instructions, scenarios, and

questions were back-translated from Korean to English by independent translators to ensure accuracy.

To measure perceived job mobility (Chen et al., 2009), participants indicated the extent to which they agreed with four statements (from

5 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree; e.g.,

‘‘Compared to other societies, it is relatively easy for people in

our society to change from one profession to a totally different profession.’’). We dropped one reverse-coded item (‘‘In our society,

even when people change professions, the business network they

have established in their professions will still be very useful for

their new profession.’’) due to low correlations with the other

items ( .29, .10, and .06; Kim & Mueller, 1978) and low reliability

(Hinkin, 1995). The final three items were averaged (a = .63), with

higher numbers reflecting higher levels of perceived job mobility.

In the dishonest condition, participants read: ‘‘Imagine the following scenario: You recently completed some work with another

individual. You just found out that the individual was dishonest

about some key information regarding the interaction. As a result,

you only received $100. You would have received 50% more if the

other individual had given you honest information.’’ Thus, in the

dishonest condition, participants expected $150 and suffered a

$50 loss. In the honest condition, participants were told they

received $100 because the other person was honest; they expected

$50 and enjoyed a $50 gain. These scenarios ensured that the gain

1

We used three consistent criteria for excluding participants: (1) participants

whose responses indicated that they were not paying attention (e.g., answered all

5’s or 5’s across all scale items, even though items were reverse coded), (2)

participants who completed the survey too quickly or too slowly, given the suggested

time allotment and mean completion times (2.5 standard deviations above and below

the mean), and (3) participants who failed the experimental manipulation checks.

Twelve participants were excluded in Experiments 1 and 3 because of their lack of

attention. Six participants were excluded in Experiment 2 because the survey was not

completed within the time allotted. Finally, 9 participants were excluded from

Experiment 2 because they failed the manipulation check of whether the other person

acted honestly or dishonestly in Gneezy’s Deception Game.

from the honesty and the loss from the dishonesty was equivalent

at $50.

To ensure that Korean participants understood the monetary

stake, the US dollar amount was also presented in an equivalent

amount of Korean Won, based on the approximate exchange rate

($1 = 1000 Korean Won; adapted from Wang & Leung, 2010). For

example, a monetary portion of the dishonest scenario stated,

‘‘As a result, you only received $100 (approximately 100,000 Korean Won).’’

Finally, participants were asked about two types of responses to

the honest or dishonest actor. They were told as they answered

each question to imagine that response as the only one they had

available to them. The appearance of each question was

counterbalanced.

Social inclusion or exclusion. Participants indicated the degree to

which they would (in the honest condition) socially include the

individual in or (in the dishonest condition) socially exclude the

individual from their social circle (1 = not at all to 6 = extremely).

Monetary reward or punishment. Following Wang and her colleagues (Wang et al., 2009, 2011; Wang & Leung, 2010), respondents could spend hypothetical money to reward (in the honest

condition) or punish (in the dishonest condition) at a personal cost

set at one-tenth of the amount the individual would be rewarded

or punished. This information was presented in $20 increments,

from $0 to $100 (e.g., participants who punished $20 selected,

‘‘Punish the individual $20 (at a cost of $2).’’ For Korean participants, the dollar amount was also translated into Korean Won.

Results and discussion

The effect of culture on responses to honesty and deception. The

dependent variables were subjected to a 2 (behavior: honest versus

dishonest) by 2 (culture: American versus Korean) by 2 (strategy:

social inclusion/exclusion versus monetary reward/punishment)

mixed-model analysis of variance (ANOVA). The third factor was

measured as a within-participant factor.2 A three-way interaction

emerged, F(1, 217) = 64.00, p < .001, suggesting the differential effects

of culture and behavior on the type of response utilized. To explore

the contrasts, we analyzed the effects of culture and behavior on each

type of response separately.

Social inclusion or exclusion. Participants were more likely to

include honest actors (M = 4.02, SD = 1.20) than exclude dishonest

actors (M = 3.56, SD = 1.46), F(1, 217) = 18.76, p < .001, d = .34. Also,

Americans (M = 4.11, SD = 1.22) were more likely than Koreans

(M = 3.15, SD = 1.39) to include and exclude the actors,

F(1, 217) = 28.94, p < .001, d = .73. An interaction emerged,

2

A correlation emerged between perceived job mobility and participant age,

r(219) = .28, p < .001. To ensure that participant age was not driving our job mobility

effects, we performed the analyses controlling for participant age and the results

remained consistent. Therefore, the results reported do not include participant age as

a control.

Please cite this article in press as: Whitson, J., et al. Responses to normative and norm-violating behavior: Culture, job mobility, and social inclusion and

exclusion. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes (2014), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2014.08.001

J. Whitson et al. / Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes xxx (2014) xxx–xxx

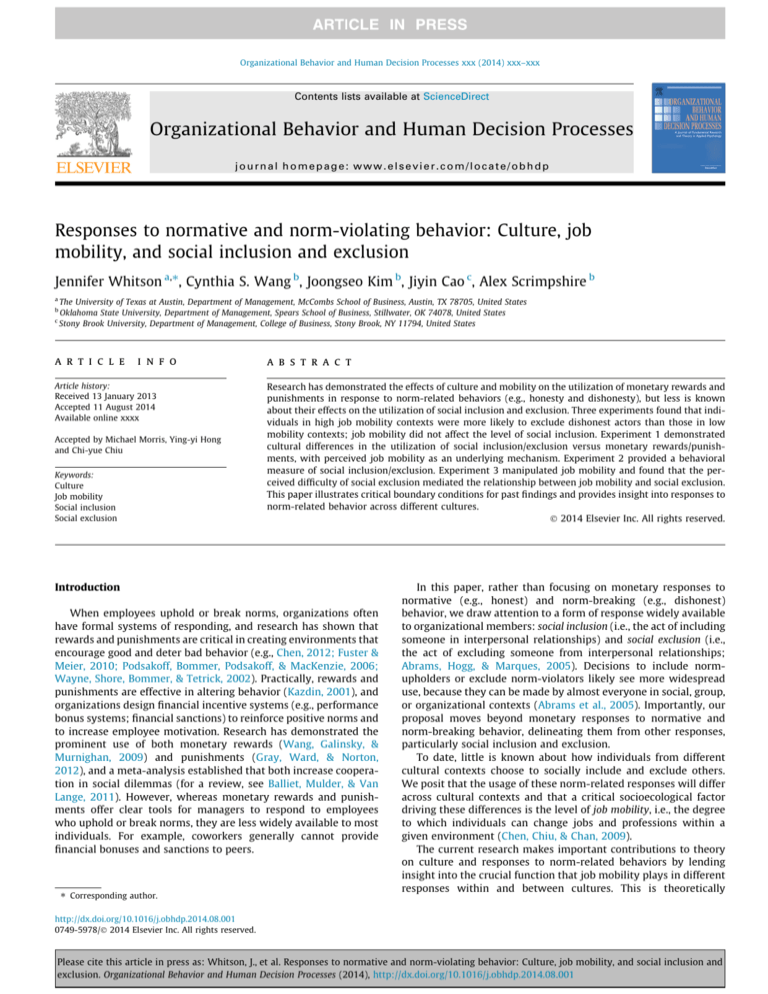

Fig. 1. Effect of perceived job mobility (mean ± one standard deviation) and

behavior on social inclusion and exclusion, Experiment 1.

F(1, 217) = 29.90, p < .001, such that Americans (M = 4.21, SD = 1.21)

were more likely than Koreans (M = 2.37, SD = 1.08) to exclude dishonest actors, t(217) = 7.85, p < .001, d = 1.60; Americans (M = 4.01,

SD = 1.22) and Koreans (M = 4.03, SD = 1.18) did not differ in the

extent to which they included honest actors, t(217) = .06, p = .95,

d = .02.

Monetary response. An interaction emerged, F(1, 217) = 32.60,

p < .001. Americans (M = 2.99, SD = 2.06) monetarily punished less

than did Koreans (M = 4.35, SD = 1.23), t(217) = 3.99, p < .001,

d = .80. In contrast, Americans (M = 4.21, SD = 1.89) monetarily

rewarded more than did Koreans (M = 2.74, SD = 1.01),

t(217) = 4.09, p < .001, d = .97. These results replicate those by

Wang and Leung (2010). No main effects emerged for culture,

F(1, 217) = .04, p = .84, d = .002, or for rewarding and punishing,

F(1, 217) = .61, p = .43, d = .14.

The effect of perceived job mobility on responses to honesty and

deception. We ran separate linear regressions for each dependent

variable, with perceived job mobility and behavior as independent

variables.

Social inclusion and exclusion. A Job Mobility Behavior interaction emerged for the utilization of social inclusion or exclusion,

b = .18, SE = .08, t(217) = 2.25, p = .03. As perceived mobility

increased, exclusion increased, b = .14, SE = .05, t(217) = 2.53,

p = .01. However, perceived mobility did not influence inclusion,

b = .04, SE = .06, t(217) = .70, p = .49 (see Fig. 1).

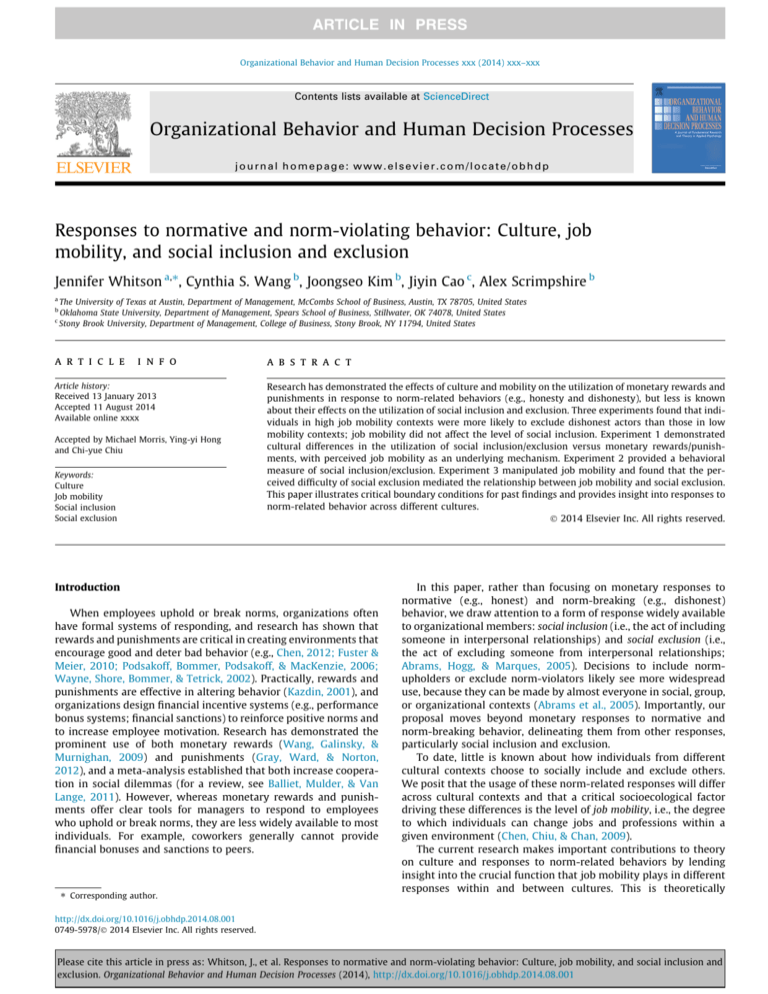

Monetary response. A Job Mobility x Behavior interaction

emerged for the amount of monetary response, b = .43, SE = .11,

t(217) = 4.06, p < .001. As perceived mobility increased, the

amount of monetary punishment decreased, b = .21, SE = .07,

t(217) = 2.89, p = .004, but the amount of monetary reward

increased, b = .22, SE = .08, t(217) = 2.85, p = .005 (see Fig. 2).

Moderated path analyses. We hypothesized that cultural differences in perceived job mobility explain why Americans and Koreans differ in their responses. To test this hypothesis, we ran two

moderated path analyses, one with social inclusion/exclusion and

one with monetary reward/punishment as the dependent variable.

For each moderated path analysis, we utilized the Second Stage

and Direct Effect Moderation Model (Edwards & Lambert, 2007). In

this model, moderation occurs between the mediator and the

dependent variable (i.e., second stage moderation) and the independent variable and the dependent variable (i.e., direct effect

moderation). Our hypothesis was tested via two multiple regression models (see Table 2 for regression results). The first regression

5

Fig. 2. Effect of perceived job mobility (means ± one standard deviation) and

behavior on amount of monetary reward and punishment, Experiment 1.

tested and confirmed that Americans (M = .64; SD = 2.07) perceive

themselves to possess higher job mobility than Koreans

(M = 1.84; SD = 1.77), t(219) = 8.86, p < .001, d = 1.29. The second

regression tested whether the actor’s behavior influences the

extent to which perceived job mobility and culture affect the utilization of each norm enforcement strategy. We discuss the results

for each dependent variable and the overall path analysis significance testing below.

Social inclusion and exclusion. We predicted that Americans

socially exclude more and include less than Koreans, and that these

relationships are mediated by levels of perceived job mobility. We

regressed social inclusion/exclusion on culture (independent variable), job mobility (mediator), behavior (moderator), the culture behavior interaction, and the job mobility x behavior

interaction.

A bootstrap procedure with 5000 samples tested the magnitude

of the direct, indirect, and total effects at each level of the moderator (honest versus dishonest). We first consider results in the dishonest condition. The direct effect of culture on exclusion emerged,

with a 95% bias-corrected confidence interval (CI) of [ 2.41, 1.46]

not overlapping with zero. Although trending, the indirect effect,

which tested job mobility as a mediator between culture and

exclusion, did not emerge, with a 90% CI of [ .07, .32]. However,

the indirect effect, when combined with the direct effect, produced

a total effect, with a 99% CI of [ 2.40, 1.24]. These findings provide support for H1SE and H2SE: Americans perceived themselves

to possess greater job mobility than Koreans, which translated into

increased social exclusion.

In the honest condition, the CIs of the direct [ .79, .57], indirect

[ .23, .50], and total effects [ .50, .47] all overlapped with zero.

Therefore, H1SI and H2SI were not supported: no differences in

inclusion emerged by culture, and perceived job mobility did not

mediate the effects of culture on social inclusion.

Monetary response. We replicated Wang and Leung (2010)’s

study by regressing monetary reward/punishment on culture

(independent variable), job mobility (mediator), behavior (moderator), the culture behavior interaction, and the job mobility behavior interaction.

We again utilized the bootstrapping method by Edwards and

Lambert (2007). In the dishonest condition, we found a direct effect

of culture on monetary punishment with a 95% CI of [.39, 1.84].

Although the indirect effect through perceived job mobility did

Please cite this article in press as: Whitson, J., et al. Responses to normative and norm-violating behavior: Culture, job mobility, and social inclusion and

exclusion. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes (2014), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2014.08.001

6

J. Whitson et al. / Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes xxx (2014) xxx–xxx

Table 2

Second stage and direct effect moderated path analysis results for social inclusion/exclusion and monetary reward/punishment, Experiment 1.

Perceived job mobility

Mediator variable model

b

Constant

Culture (0 = US; 1 = South Korea)

.84

2.48

Dependent variable model

Conditional indirect effects

Honesty

Direct

Indirect

Total

Dishonesty

Direct

Indirect

Total

p

<.001***

<.001***

.16

.28

Social inclusion/exclusion

b

Constant

Culture (0 = US; 1 = South Korea)

Job Mobility

Behavior (0 = Honesty; 1 = Dishonesty)

Job mobility Behavior

Culture Behavior

SE

Monetary reward/punishment

SE

4.07

.14

.06

.17

.01

1.80

Boot effect

.14

.14

.002

1.94

.12

1.82

.15

.30

.06

.21

.08

.40

p

b

<.001***

.64

.37

.41

.93

<.001***

4.14

1.28

.07

1.08

.17

2.41

Conf. interval

Boot effect

SE

p

.22

.44

.09

.31

.12

.58

<.001***

.004**

.46

.001**

.16

<.001***

Conf. interval

[ .79, .57]

[ .23, .50]

[ .50, .47]

1.28

.17

1.44

[ 2.05, .43]*

[ .63, .29]

[ 1.97, .84]*

[ 2.41, 1.46]*

[ .07, .32]

[ 2.40, 1.24]**

1.13

.26

1.39

[.39, 1.84]*

[ .15, .70]

[.75, 1.98]*

Note: N = 221.

Unstandardized regression coefficients are reported. Bootstrap sample size = 5000.

*

p 6 .05,

**

p 6 .01,

***

p 6 .001.

+

p 6 .10.

not emerge [ .15, .70], the indirect and direct effects combined to

produce a total effect [.75, 1.98]. In the honest condition, a direct

effect of culture on monetary reward emerged [ 2.05, .43]. The

indirect effect did not emerge [ .63, .29], but the total effect of culture on monetary reward did [ 1.97, .84].

Experiment 1 replicated findings by Wang and Leung (2010)

that Americans were less likely than Koreans to monetarily punish

a dishonest actor, but were more likely to monetarily reward an

honest actor. Importantly, decisions to socially exclude versus

include portrayed a considerably different pattern of effects. As

predicted, Americans were more likely than Koreans to exclude

dishonest actors, with this effect driven by higher perceived job

mobility. However, contrary to our predictions, Americans and

Koreans did not differ in their levels of social inclusion.

Experiment 2: Behavioral social inclusion and exclusion

Experiment 1 demonstrated clear cultural patterns and so

Experiments 2 and 3 focused on the proposed mechanism, job

mobility, to clarify its effects. Experiment 2 moved beyond the scenario used in Experiment 1 by placing individuals in a context that

allowed behavioral choices. We used a modified version of

Gneezy’s (2005) Deception Game, in which one player sends a

truthful or misleading message and the other player chooses

whether to believe it, with their decisions jointly determining their

payoffs.

Participants also played Cyberball (Williams, Yeager, Cheung, &

Choi, 2012), in which they chose to include or exclude others in an

on-line ball tossing game. This paradigm was designed to duplicate

inclusion and exclusion decisions that occur in face-to-face group

interactions (Williams & Sommer, 1997) and has demonstrated

similar effects as face-to-face paradigms (Williams, 2009). We

believe this paradigm has implications for organizational settings

in which group members often engage in interconnected work

tasks and choose if and when to interact with others.

Method

Participants and design. One-hundred nineteen undergraduate

participants from a US southwestern university completed this

study for extra credit (80 females and 39 males; 50 Caucasians,

41 Asians, 24 Hispanics, and 4 other races; mean age = 29.61,

SD = 8.53, range = 18–40) and were randomly assigned to a dishonest or honest condition. We also measured participants’ perceived

job mobility (see Table 3 for descriptive statistics and correlation

matrix).

Procedure. We used the same job mobility scale as in Experiment 1 (Chen et al., 2009), and dropped the same item because

of decreased reliability and low correlations with the other items

(.20, .05, and .002). The three items were averaged (a = .60), with

higher numbers reflecting higher levels of perceived job mobility.

Stage 1. Participants were told they would be completing two

stages during the study. In Stage 1, participants took part in the

modified version of Gneezy’s (2005) Deception Game. Participants

were informed that they would be assigned at random to play as

Player A or Player B with another randomly chosen participant.

In reality, every participant played as Player B, and we manipulated

Player A’s choices. Participants were told that only Player As would

have the payoff matrix with two options (Options A and B) based

on a fictitious currency (MAXs). Participants (Player Bs) could not

see the payoff matrix, but were asked to choose Option A or B;

depending on the option selected, they would earn more or less

than Player A.

The instructions also indicated that, prior to their option choice,

Player As would send participants one of two messages: ‘‘Option A

earns you more than Option B’’ or ‘‘Option B earns you more than

Option A.’’ The instructions made it clear that only one of these messages was accurate. Because we controlled Player As’ choices, the

message always indicated that participants would do best by choosing Option A. Research (e.g., Gneezy, 2005) indicates that a large

majority of participants believe the message and choose Option A.

Please cite this article in press as: Whitson, J., et al. Responses to normative and norm-violating behavior: Culture, job mobility, and social inclusion and

exclusion. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes (2014), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2014.08.001

7

J. Whitson et al. / Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes xxx (2014) xxx–xxx

Table 3

Descriptive statistics and variable inter-correlations, Experiment 2.

Variables

Mean

SD

1

2

3

3a

3b

3c

3d

4

5

1. Job mobility

2. Behavior (0 = Honesty; 1 = Dishonesty)

3. Total number of passes to prior player

a. Round 1

b. Round 2

c. Round 3

d. Round 4

4. Age

5. Sex (0 = Male; 1 = Female)

.35

.54

1.41

.39

.20

.34

.49

29.61

.67

2.09

.50

.92

.49

.40

.47

.50

8.53

.47

1.00

.09

.03

.11

.08

.13

.01

.02

.11

1.00

.29**

.25**

.09

.02

.23*

.01

.01

1.00

.60**

.39**

.28**

.68**

.11

.08

1.00

.10

.24**

.43**

.17

.04

1.00

.003

.01

.02

.18*

1.00

.20*

.01

.07

1.00

.01

.04

1.00

.05

1.00

Note: N = 119.

*

Correlation is significant at p 6 .05.

**

Correlation is significant at p 6 .01.

After choosing Option A or B, participants in the honest condition

were told that Player A’s message was true, that they would receive

40 MAXs in Stage 1, and that ‘‘you would have received 50% less if

you had chosen the other option.’’ In the dishonest condition, participants were told that Player A’s message was not true, that they

would receive 40 MAXs in Stage 1, and that ‘‘you would have

received 50% more if you had chosen the other option.’’ Thus, their

payoffs were identical, but were framed as either an equivalent

gain or a loss resulting from a truth or a lie, respectively.

Stage 2. After completing Stage 1, participants then moved on to

Stage 2, in which they played an adapted version of Cyberball

(Williams et al., 2012). Participants were informed that they would

be interacting with three other participants who were simultaneously online during the study, one of whom was the honest or

dishonest actor from Stage 1. On the computer screen, participants

saw images of four figures. The participant was labeled as ‘‘You

(Player 2)’’ and the player from Stage 1 as ‘‘Prior Player 1.’’ The

two new players were labeled, ‘‘New Player 3’’ and ‘‘New Player

4’’, respectively. We controlled the actions of the other three players at all times.

Participants started the game in possession of the ball and were

asked who they wanted to throw it to: ‘‘Prior Player 1’’, ‘‘New Player

3’’ or ‘‘New Player 4’’. We measured participants’ tossing behavior,

with participants’ choices providing a measure of inclusion or

exclusion. To make tossing decisions more salient, emphasis was

placed on participants mentally visualizing the ball-tossing

between players; the figures and ball were animated on the computer, with the animation reflecting the participants’ tossing decisions and the other players’ subsequent reciprocation. To

standardize tossing decisions, after the participant tossed the ball,

the receiver tossed the ball back to the participant (e.g., if the participant tossed the ball to New Player 3, New Player 3 would return

the ball to the participant). Each back and forth tossing exchange

was coded as one round. Because passes were pre-programmed to

be returned to the participant, the game only included four rounds

to enhance the realism and reduce suspicion of the experience.

Results and discussion

Number of passes to Prior Player 1. We began by analyzing each

round separately. For Round 1, a binomial logistic regression analysis resulted in a Job Mobility x Behavior interaction, b = .41,

SE = .21, Wald = 3.75, p = .05 (see Fig. 3). As perceived job mobility

increased, the odds that the ball would be passed to the dishonest

actor decreased, b = .41, SE = .18, Wald = 5.57, p = .02, suggesting

that the level of job mobility was positively associated with the

usage of social exclusion. Following honesty, however, perceived

job mobility did not influence the odds of the ball being passed

to the honest actor, b = .005, SE = .12, Wald = .002, p = .97. Separate logistic regression analyses were conducted for Rounds 2, 3,

Fig. 3. Effect of perceived job mobility (mean ± one standard deviation) and

behavior on the probability of passing the ball to the prior player, Experiment 2

(Round 1).

and 4. The Job Mobility x Behavior interaction did not emerge

across the final three rounds (all p’s > .39).

To further explore the effects, we aggregated the number of

passes participants made to the Prior Player 1 across all four

rounds, with higher number reflecting higher inclusion/less exclusion, e.g., tossing the ball to Prior Player 1 in all four rounds was

coded as 4. We tested the effect of perceived job mobility and

behavior on the amount of social inclusion or exclusion. Participants tossed the ball to honest players more than to dishonest

players, b = .53, SE = .17, t(115) = 3.19, p = .002. However, no

interaction emerged, b = .02, SE = .08, t(115) = .24, p = .81.

Overall, we found no differences in social inclusion across the

levels of mobility. Conversely, individuals from high mobility contexts were more likely to exclude dishonest actors in the initial

Cyberball round than individuals from low mobility contexts, with

the effects dissipating in later rounds. It is possible that the later

rounds attenuated the effects of perceived job mobility because a

multi-round interaction with the same individuals would, over

time, reduce a participants’ sense of mobility within their current

set of interpersonal interactions. We discuss this possibility more

extensively in the general discussion.

Experiment 3: The difficulty of socially excluding

Experiment 3 aimed to accomplish several goals. First, as Experiments 1 and 2 measured perceived job mobility, Experiment 3

manipulated job mobility to test causality. Although Experiments

1 and 2 suggest that job mobility will not influence social inclusion,

we nonetheless measure it to be comprehensive. Second, we

Please cite this article in press as: Whitson, J., et al. Responses to normative and norm-violating behavior: Culture, job mobility, and social inclusion and

exclusion. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes (2014), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2014.08.001

8

J. Whitson et al. / Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes xxx (2014) xxx–xxx

improved the single-item measures of social inclusion and exclusion employed in Experiment 1 by using multiple-item measures

so as to better test the validity of our findings. Third, we ensured

that all aspects of the design were organizationally-related: our

participants were working adults, our scenarios situated participants within a working context, and our manipulation of mobility

was job-specific. Finally, we examined potential mechanisms

underlying our effects. In particular, we proposed that social exclusion will be more prevalent in high mobility environments because

it is less difficult to implement.

Procedure. Participants were randomly assigned to a high versus

low job mobility condition. We manipulated job mobility by asking

participants to read a scenario containing job statistics for a hypothetical country (Chen et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2011). Participants

in the low job mobility condition read: ‘‘Due to its government’s

labor policies, the job mobility in Country X is extremely low.

According to the research statistics provided by the National Academy of Social Sciences, the majority of the people in Country X

have worked in only 1 or 2 jobs in the same occupation throughout

their lifetime. About one third of the people who are older than

50 years of age still remain in their first job.’’

Participants in the high job mobility condition read a scenario in

which the job mobility in Country X was extremely high, with statistics showing that people in Country X had worked in 3–6 jobs

and that the percentage of people who remain in their first job

decreased after the age of 30. Two supporting graphs were presented with each condition.

Participants in both conditions were asked to imagine how they

would prepare for the job market if they were a citizen of Country

X and describe that preparation in as much detail as possible.

Social inclusion or exclusion. After the job mobility manipulation,

participants received the same scenario as in Experiment 1. Participants indicated the degree to which they would socially exclude

(in the dishonest condition) or socially include (in the honest condition) the actor. Social exclusion (inclusion) was measured using

the following three questions (adapted from Ferris, Brown, Berry,

& Lian, 2008): ‘‘After the incident, to what extent would you ignore

(include) the individual at work?’’, ‘‘. . .would you leave (stay in)

the area when the individual entered?’’, and ‘‘...would you be unresponsive (responsive) to the individual’s greeting at work?’’, 1 = not

at all to 6 = extremely. These items were averaged to form a measure of social exclusion (a = .86) and social inclusion (a = .81).

Perceived difficulty of social inclusion or exclusion. Participants

were then asked to rate how difficult it would be to implement

these strategies using four items, e.g., ‘‘How hard would it be for

you to do these things?’’, 1 = not at all to 6 = extremely. These items

were averaged to form a difficulty measure (a = .91).

Perceived effectiveness of socially including or excluding. Participants also rated eight items measuring the effectiveness of these

social exclusion (inclusion) strategies, e.g., ‘‘How likely would the

individual be to repeat the dishonest (honest) act if you did these

things?’’, ‘‘How strong are these punishments (rewards)?’’, ‘‘How

negatively (positively) affected would the individual have been

by these things?’’, 1 = not at all to 6 = extremely. These items were

averaged to form an effectiveness measure (a = .93).

To confirm that difficulty and effectiveness were two independent constructs, the two measures were analyzed via a principal

components analysis (PCA) with varimax rotation with kaiser normalization. Results revealed a two-factor structure (eigenvalues

greater than 1.0) explaining 73% of the variance and supporting

the discriminant validity of difficulty and effectiveness. All the

Hypothesis 3. Individuals in high job mobility contexts perceive

social exclusion as less difficult than individuals in low mobility

contexts, which translates into increased social exclusion.

An alternative explanation for why low job mobility was associated with decreased social exclusion in Experiments 1 and 2

involves the perceived effectiveness of social exclusion. As individuals in a low mobility environment are more likely to have collective self-construals (Oishi, Lun et al., 2007), it is not surprising that

their social exclusion causes greater fear and pain (Kim &

Markman, 2006) and is perceived to be a more effective social control (Hashimoto & Yamagishi, 2013) than social exclusion for individuals in a high mobility environment.

Furthermore, theory suggests that people are aware that, ceteris

paribus, punishments are felt more intensely than rewards

(Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Finkenauer, & Vohs, 2001), and so tend

to use them more sparingly (Wang et al., 2009). If this is the case,

it logically follows that as social exclusion becomes more excruciating for those excluded (as in low mobility contexts), individuals

may feel they need to use this method less extensively. In short, an

important question is whether this rationale could also explain the

social exclusion findings from Experiments 1 and 2: that is,

whether individuals from low mobility contexts are more moderate in their use of social exclusion than those from high mobility

contexts because they believe that not as much exclusion is necessary to be an effective deterrent. We therefore included a measure

of perceived effectiveness to test this alternative explanation.

Method

Participants and design. One-hundred fifteen working adults in

the United States (45 females and 70 males; 90 Caucasians, 9

Asians, 6 Hispanics, 5 African Americans, and 5 other races; mean

age = 31.35, SD = 11.66, range = 18–67) were recruited via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk), an online survey program which

has been proposed to provide a diverse and representative sample

while yielding data that are equal to or exceed the psychometric

standards in established research (see Buhrmester, Kwang, &

Gosling, 2011). The design was a 2 (job mobility: high, low) 2

(behavior: honest, dishonest) between-participants design (see

Table 4 for descriptive statistics and correlation matrix).

Table 4

Descriptive statistics and variable inter-correlations, Experiment 3.

Variables

Mean

SD

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

.51

.55

2.50

3.62

3.99

31.35

.39

.50

.50

1.31

1.11

1.52

11.66

.49

1.00

.08

.10

.06

.13

.04

.15

1.00

.33**

.47**

.70**

.08

.05

1.00

.12

.44**

.06

.12

1.00

.62**

.05

.10

1.00

.04

.13

1.00

.43**

1.00

Manipulated job mobility (0 = Low; 1 = High)

Behavior (0 = Honesty; 1 = Dishonesty)

Difficulty

Effectiveness

Social inclusion or exclusion

Age

Sex (0 = Male; 1 = Female)

Note: N = 115.

*

Correlation is significant at p 6 .05.

**

Correlation is significant at p 6 .01.

Please cite this article in press as: Whitson, J., et al. Responses to normative and norm-violating behavior: Culture, job mobility, and social inclusion and

exclusion. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes (2014), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2014.08.001

J. Whitson et al. / Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes xxx (2014) xxx–xxx

Table 5

First stage and direct effect moderated path analysis results for social inclusion/

exclusion, Experiment 3.

Difficulty

Mediator variable model

b

SE

p

Constant

Job mobility

Behavior

Job mobility Behavior

1.83

.36

1.37

1.03

.26

.34

.33

.46

<.001***

.29

<.001***

.03*

Dependent variable model

b

SE

p

Constant

Job mobility

Behavior

Job mobility Behavior

Difficulty

5.71

.12

2.20

.55

.24

.26

.29

.30

.40

.08

<.001***

.68

<.001***

.17

.004**

Conditional indirect effects

Boot effect

Conf. interval

Social inclusion/exclusion

Honesty

Direct

Indirect

Total

Dishonesty

Direct

Indirect

Total

.12

.09

.21

.43

.16

.59

[ .49, .26]

[ .28, .02]

[ .59, .20]

[ .07, .97]

[.003, .47]*

[.06, 1.15]+

Note: N = 115.

Unstandardized regression coefficients are reported. Bootstrap sample size = 5000.

*

p 6 .05,

**

p 6 .01,

***

p 6 .001.

+

p 6 .10.

items were significantly loaded on the expected factors with no

cross-loadings.

Results and discussion

Social inclusion and exclusion. The likelihood of socially including/excluding the actor was submitted to a Job Mobility x Behavior

between-participants ANOVA. Participants were more likely to

include an honest actor (M = 5.16, SD = .73) than to exclude a dishonest actor (M = 3.03, SD = 1.31), F(1, 111) = 111.31, p < .001. An

interaction emerged, F(1, 111) = 3.84, p = .05. High mobility participants (M = 3.33, SD = 1.38) were more likely than low mobility

participants (M = 2.75, SD = 1.20) to socially exclude a dishonest

actor, t(111) = 2.16, p = .03; mobility did not influence social inclusion decisions (high mobility: M = 5.07, SD = .77 versus low mobility: M = 5.28, SD = .67), t(111) = .69, p = .49.

Moderated path analyses. We hypothesized that difficulty, but

not effectiveness, would explain the effect of job mobility on social

exclusion. To test this hypothesis, we used two First Stage and

Direct Effect Moderation Models (Edwards & Lambert, 2007), one

with difficulty as the mediator, the other with effectiveness as

the mediator. In this model, moderation occurs between the independent variable and the mediator (i.e. first stage moderation) and

the independent variable and the dependent variable (i.e., direct

effect moderation).

Difficulty. To test H3, we ran the moderated path analysis utilizing two regressions (see Table 5). The mediator variable model

tests the interactive effect of manipulated job mobility and behavior on difficulty.3 A Job Mobility Behavior between-participants

ANOVA yielded an interaction, F(1, 111) = 4.97, p = .03, with participants in the high job mobility condition (M = 2.53, SD = 1.32)

3

We reported ANOVA results for ease of interpretation. As shown in Table 5, the

moderated path analysis utilized OLS regressions.

9

viewing social exclusion as less difficult to implement than those

in the low job mobility condition (M = 3.20, SD = 1.43),

t(111) = 2.15, p = .03, d = .49. Differences did not emerge for social

inclusion (high mobility condition (M = 2.19, SD = 1.06) versus low

mobility condition (M = 1.83, SD = .92)), t(111) = 1.06, p = .29,

d = .36. Participants also viewed it as more difficult to exclude a dishonest actor (M = 2.88, SD = 1.41) than to include an honest actor

(M = 2.03, SD = 1.01), F(1, 111) = 13.86, p < .001, d = .69. The main

effect of job mobility did not emerge, F(1, 111) = .42, p = .52, d = .21.

The dependent variable model tests whether the increased difficulty of implementing inclusion/exclusion strategies decreased

their utilization. The more difficult participants thought it was to

include/exclude, the less likely they were to do so, b = .24,

SE = .08, t(110) = 2.98, p = .004.

As with Experiment 1, we used the bootstrapping method with

5000 samples and constructed bias-corrected CIs. In the dishonest

condition, indirect effect was significant [.003, .47] using a 95% CI.

The indirect effect combined with the direct effect [ .07, .97], produced a total effect [.06, 1.15] using a 90% CI. This analysis marginally supported H3: individuals in the high job mobility condition

viewed exclusion as less difficult to implement than those in the

low job mobility condition, which translated into increased social

exclusion. In the honest condition, CIs of the indirect [ .28, .02],

direct [ .49, .26], and total effects [ .59, .20] overlapped with zero,

indicating that difficulty did not mediate the relationship between

job mobility and social inclusion.

Effectiveness. We tested whether participants in the low job

mobility condition utilized less social exclusion because they perceived it as more effective. Participants perceived inclusion

(M = 4.19, SD = .95) to be more effective than exclusion (M = 3.15,

SD = 1.02), F(1, 111) = 30.75, p < .001, d = 1.06. However, the Job

Mobility Behavior interaction, F(1, 111) = .31, p = .58, and the

main effect of job mobility, F(1, 111) = .05, p = .83, did not emerge.

Due to the absence of these effects, we conclude that effectiveness

did not mediate the effects of job mobility on social exclusion, ruling out the alternative hypothesis.

Experiment 3 confirmed a causal relationship between job

mobility and social exclusion. Participants in the high mobility

condition were more likely to exclude dishonest actors than participants in the low mobility condition. Furthermore, the relationship

between mobility and exclusion was mediated by the difficulty of

exclusion, but not by effectiveness. No effects were found for social

inclusion.

General discussion

Across three experiments, using different cultural samples

(Americans, South Koreans), research methods (correlational,

experimentally manipulated), and measures of social inclusion

and exclusion (scenarios, behavioral), we consistently found that

individuals in high perceived job mobility contexts were more

likely to socially exclude dishonest actors than those in low perceived job mobility contexts, and that perceived job mobility did

not affect levels of social inclusion.

Experiment 1 demonstrated clear cultural differences in the utilization of social inclusion/exclusion versus monetary rewards/

punishments. Specifically, when employing monetary incentives,

Americans punished a dishonest actor less and rewarded an honest

actor more than South Koreans; however, Americans socially

excluded a dishonest actor more than South Koreans, whereas no

differences by job mobility emerged for the social inclusion of an

honest actor. Importantly, perceived job mobility was a contributing underlying mechanism. Experiment 2 provided a behavioral

measure of social inclusion and exclusion. It found that as perceived job mobility increased, the likelihood of tossing the ball to

Please cite this article in press as: Whitson, J., et al. Responses to normative and norm-violating behavior: Culture, job mobility, and social inclusion and

exclusion. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes (2014), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2014.08.001

10

J. Whitson et al. / Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes xxx (2014) xxx–xxx

a dishonest actor in the initial round of the game decreased, suggesting increased social exclusion. Experiment 3 examined the proposed theoretical mechanism and found that the perceived

difficulty, but not the perceived effectiveness, of socially excluding

a dishonest actor mediated the relationship between job mobility

and social exclusion. It also determined causality by showing that

manipulated perceptions of job mobility increased social exclusion.

As in Experiment 1, job mobility did not affect social inclusion

decisions in Experiments 2 or 3. In sum, these experiments provide

support for an emergent socioecological perspective that sheds

insight into how culture influences responses to norm-violating

behavior.

Critically, this research goes beyond past work that has focused

on cultural comparisons of monetary reward and punishment

responses. Our findings illustrate a new cultural pattern of results

and a boundary condition for previous work. While previous work

on reward and punishment behaviors showed that East Asians

were more monetarily punitive than Westerners, our results show

that Westerners can be just as punitive when utilizing a different

form of response. An individual’s choice to punish may depend

on the situational affordances of their culture and context. We

hope that this research will stimulate investigation into different

forms of responses, thereby expanding understanding of culture,

mobility, social norms, and responses to normative and norm-violating behaviors.

This research offers important practical implications for individuals in organizational contexts. An employee working abroad,

or even those who choose to move to a new company, should be

aware that differing contextual levels of job mobility may lead to

organizational cultures whose responses to norm-violating behavior may differ dramatically from what the employee is used to. For

instance, a manager who is hired from a stable (i.e., low mobility)

organization with clearly defined sanctioning systems may gain a

reputation in a more quickly changing entrepreneurial (i.e., high

mobility) organization for being unnecessarily punitive. Instead,

members of these entrepreneurial organizations may be used to

responding to norm-violating behaviors more informally, for

example, by excluding others. In sum, our research implies that

managers responding to bad behavior risk violating cultural expectations if they do not take into account the contextual mobility of

their organization.

Future directions

The findings that job mobility or national culture are not associated with social inclusion warrants further discussion. Because

participants’ choices to socially include were based largely around

decisions to maintain or deepen, rather than form, ties (e.g., in

Experiment 1, keeping an existing member of a social group; in

Experiment 2, passing a ball to another player; in Experiment 3,

social inclusion of a coworker), this may be why no differences

emerged. It may be easy for individuals in both high and low job

mobility contexts to maintain a relationship with honest actors.

Future studies could go beyond inclusion strategies based on

‘‘friendly defaults’’ to develop stronger manipulations or measures

to capture social inclusion strategies that require more effort (e.g.,

tie formation).

Our findings in Experiment 2 suggest that social exclusion decisions are contextually sensitive and individuals are likely to adjust

their reactions once the environmental mobility changes. For

example, whereas participants high in perceived job mobility were

less likely to toss the ball to the dishonest player in the initial

round of Cyberball, this effect dissipated over the next three

rounds. One possibility is that the norm of inclusion accentuated

by the Cyberball game resulted in an increase in participants’

inclusionary behavior over time, regardless of their respective

levels of job mobility. Another possibility is that multiple rounds

with the same three players engendered a perception of low mobility in which participants felt inextricably tied to the other players.

A further analysis using a median split to form high and low mobility groups suggests that these explanations may indeed have

played a part: participants in both low and high mobility contexts

in the final two rounds responded in a manner similar to participants in low mobility contexts in the initial round (i.e., in the first

round, only 14% of participants in high mobility contexts tossed the

ball to the dishonest actor, as compared to 37% of the participants

in low mobility contexts; in the final two rounds, between 30% and

43% of both groups tossed the ball to the dishonest actor). Future

research should examine this dynamic to better understand the

malleability of perceived mobility, and when the immediate situational context may override more stable measures of socioecological mobility (e.g., the job mobility scale utilized in Experiments 1

and 2).

A more fine-grained examination of various types of mobility

may also be worthwhile to explore. For example, whereas measures of job and relational mobility are often based on a perceived

societal mobility (i.e. how easy it is to change careers or relationships in a given environment; Chen et al., 2009; Schug et al.,

2009, 2010); measures of residential mobility are often based on

objective statistics (i.e. the number of residential moves people

have made; e.g., Oishi, Ishii, & Lun, 2009; Oishi, Lun et al., 2007;

Oishi, Rothman et al., 2007; Oishi & Schimmack, 2010; Yuki

et al., 2007). Oishi (2014) proposed that in contrast to most psychological research that examines how perceived societal mobility

affects cognition, emotion, and behavior, socioecological psychology can also employ environmental data (e.g. sex ratios in a given

environment, population density) to investigate how the objective

environment influences individual psychology.

Future research should compare the relative influences of perceived societal mobility versus objective mobility’s influence on

norm-related reactions. Moreover, it would be valuable to explore

whether the effects produced by job mobility also result from residential and relational mobility, or whether these different forms of

mobility differently influence the same phenomena. These three

types of mobility are correlated, but conceptually distinct, so

may exhibit notable differences in both their pattern and magnitude of effects. Perceived job mobility, for example, may exhibit

a stronger effect on behaviors related to organizational contexts.

In Experiment 1, we also measured perceived relational mobility

(Yuki et al., 2007; 12 items, from 1 = strongly disagree to

7 = strongly agree; e.g., ‘‘They have many chances to get to know

other people’’). A correlation between relational and job mobility

emerged, r(211) = .24, p < .001. However, the results suggested

relational and job mobility are distinct constructs: while controlling for relational mobility, the reported effects for job mobility

still hold.

Moreover, whereas the pattern of effects of relational mobility

on social inclusion/exclusion mirrored that of job mobility, the

effects were not as robust. The interaction between perceived relational mobility and behavior on the amount of social inclusion or

exclusion was in the same direction as the job mobility data but

not significant, b = .37, SE = .28, t(217) = 1.33, p = .19. This may

have occurred because the scenario specified a work-based relationship between the target individuals, thus resulting in a stronger effect for the more contextually pertinent construct of job

mobility.

It is also worthwhile to explore whether individuals react to

social inclusion and exclusion differently depending on the level

of job mobility in their environment. Although Experiment 3 found

that the level of perceived effectiveness of social inclusion and

exclusion was the same in low versus high job mobility environments, our measurement only captured the perception of the

Please cite this article in press as: Whitson, J., et al. Responses to normative and norm-violating behavior: Culture, job mobility, and social inclusion and

exclusion. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes (2014), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2014.08.001

J. Whitson et al. / Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes xxx (2014) xxx–xxx

initiator, but not the recipient, of social inclusion and exclusion. One

possibility is that when one individual decides to exclude another,

recipients in high mobility contexts will be less affected than those

in low mobility contexts; for with their higher mobility, the recipients can simply opt out of the situation, making the exclusion less

of a threat and ultimately, less of a punishment. In this case, less

threatening punishments may be balanced by the increased willingness of individuals in high mobility contexts to exclude. Thus,

the overall impact of the exclusion may in fact be the same across

contexts. Future research should try to examine this other side of

these interactions.

Conclusion

More tangible responses to norm-relevant behavior, such as

monetary incentives, generally occur via formal institutional or

organizational channels. Social inclusion and exclusion, on the

other hand, thrive in both formal arenas and in the informal webs

of human connection that lie just beneath the surface of any organizational chart. This research explores these latter forms of

responses to normative and norm-violating behaviors. Job mobility

does not alter responses to norm-relevant behavior via social

inclusion, but does via social exclusion, both within and across cultures. This provides greater insight into the relationship between

culture, mobility and the utilization of responses to normative

and norm-violating behaviors. These clashes of organizational

and national culture are not uncommon, and understanding how

different cultures choose to respond is an important step towards

reducing misinterpretations and helping improve cross-cultural

organizational dynamics.

References

Abrams, D., Hogg, M. A., & Marques, J. (2005). The social psychology of inclusion and

exclusion. New York: Psychology Press.

Bahns, A. J., Pickett, K. M., & Crandall, C. S. (2012). Social ecology of similarity: Big

schools, small schools and social relationships. Group Processes & Intergroup

Relations, 15(1), 119–131.

Balliet, D., Mulder, L. B., & Van Lange, P. A. M. (2011). Reward, punishment, and

cooperation: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 137(4), 594–615.

Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Finkenauer, C., & Vohs, K. D. (2001). Bad is stronger

than good. Review of General Psychology, 5(4), 323–370.

Baumeister, R. F., DeWall, C. N., Ciarocco, N. J., & Twenge, J. M. (2005). Social

exclusion impairs self-regulation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

88(4), 589–604.

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal

attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3),

497–529.

Baumeister, R. F., & Tice, D. M. (1990). Point-counterpoints: Anxiety and social

exclusion. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 9(2), 165–195.

Bialik, C. (2010). Seven careers in a lifetime? Think twice, researchers say. The

Wall Street Journal. <http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052748704

206804575468162805877990> .

Bian, Y., & Ang, S. (1997). Guanxi networks and job mobility in China and Singapore.

Social Forces, 75(3), 981–1005.

Borghans, L., & Golsteyn, B. H. (2012). Job mobility in Europe, Japan and the United

States. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 50(3), 436–456.

Buhrmester, M., Kwang, T., & Gosling, S. D. (2011). Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: A

new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspectives on Psychological

Science, 6(1), 3–5.

Chen, J., Chiu, C.-Y., & Chan, F. S.-F. (2009). The cultural effects of job mobility and