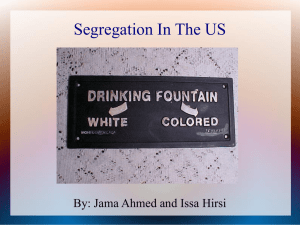

success and failure: how systemic racism trumped the brown v.

advertisement