Central Plains between Han and Tang Dynasties

advertisement

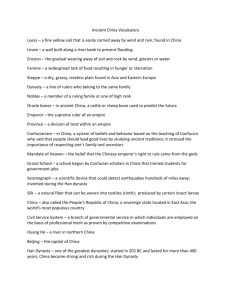

Central Plains between Han and Tang Dynasties (206 BC – 907 AD) Palazzo Venezia, Rome July 16, 2015 – February 28, 2016 From the 16th of July 2015 to the 28th of February 2016, the halls of the Fifteenth‐century Refectory of Palazzo Venezia will showcase the masterpieces of the Henan Provincial Museum, one of the largest museums of the Peopleʹs Republic of China. The exhibition will tell of the passage from the Han Dynasty – when today’s China began to take shape – to the Golden Age of the Tang Dynasty (581 AD – 907 AD). More than 100 pieces will be displayed, including a funerary robe with 2,000 jade listels woven with gold threads, and then lacquers, glazed earthenware, vases, objects made of gold, silver and jadeite. They attest to the extraordinary prosperity and cultural openness of the Tang era, when the capital of the Empire, known today as Xiʹan, was the crossroads of all trades, it used to receive ambassadors of the world and housed over a million people. The exhibition was organized by the State Administration of Cultural Heritage of the People’s Republic of China (SACH), by General Directorate of Museums of the Ministry of Cultural Heritage, Activities and Tourism of the Italian Republic (MiBACT) and by the Polo Museale of Lazio, in collaboration with the Provincial Government of Henan. It is sponsored by the Ministry of Culture of the People’s Republic of China, by the Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in Italy and by the MiBACT. The exhibition is part of the Memorandum of Understanding on Partnership for the Promotion of Cultural Heritage signed on October 7, 2010 by the Ministry of Cultural Heritage, Activities and Tourism of the Italian Republic and the State Administration of Cultural Heritage of the Peopleʹs Republic of China. The Memorandum provides for the exchange of showcasing spaces dedicated to the Chinese and Italian cultures, as to promote cultural exchange between China and Italy and to allow a greater and deeper understanding between the two peoples. The Directorate General for the enhancement of cultural heritage was granted the first, significant Italian museum abroad by the State Administration of Cultural Heritage of the Republic of China in the National Museum China in Tianʹ anmen Square in Beijing. This permanent showcase already displayed the exhibitions ʺRenaissance in Florence. Masterpieces and Protagonistsʺ in 2012 and ʺRome 17th Century: Towards Baroqueʺ in 2014. The exhibition ʺTreasures of Imperial Chinaʺ displayed this year at Palazzo Venezia is the third of five included in the agreement, after ʺArchaic Chinaʺ and ʺThe legendary tombs of Mawangduiʺ. The works on display illustrate the evolution of the Chinese civilization born and developed in the so‐called Central Plain, an area once known as the ʺCentre of the Worldʺ and expanding over today’s Henan province. They reveal how the traditional culture of the politically turbulent but intellectually flourishing period of the first Han empire (206 BC ‐ 220 AD) gave rise to the golden age of the Tang Dynasty (581‐907). The Han Dynasty (206 BC ‐ 220 AD) has played a key role in Chinese history. During this period, it consolidated the empire founded fifteen years before by the king of the powerful reign of Qin, (221‐ 210 BC) that had collapsed only four years after the death of the First Emperor. Nonetheless, the premises for the imperial grandeur were laid during his short kingdom and a complex institutional apparatus was created and perpetuated until 1911, through alternating periods of glory and stages of decay. The Han Dynasty pushed forward the project initiated by the First Emperor. The art of the Han, and particularly in the archaeological discoveries that celebrate the life after death of the deceased, reflects the imperial design and ambition of the period. The numerous terracotta statuettes, portraits, tombstones and porcelains on display were found in tombs of officials and officers of the empire. Wealth, the main theme in this period, is evoked by the complex models of houses, guard towers, wells, mills, barns and sties buried in large quantities in the tombs of the high society of the time and displayed today in the exhibition. The burial of scaled‐down reproductions of buildings began during the Han dynasty: models of three and four‐ storey guard towers, palaces with hallways, barns and various buildings of houses, theatres and homes bear witness to the autonomy achieved by the wealthiest families, who excessively expanded their properties and felt the need to protect them with walls and watchtowers. Among the buildings found in the graves, the sties seem to be surprisingly important; in Chinese culture, the pig was in fact a symbol of wealth and was eaten only on special occasions and during religious festivals. The importance attached to these models is attested by the detailed craftsmanship shown in the examples on display; grey, red and glazed ceramic rich in ornaments. Immortality took up a big part of the Han thought of the period with profound repercussions in the art, as shown by one of our most spectacular findings: the jade robe of Liang Xiaowang, made up of jade pieces of exceptional quality. This body‐length robe is made up of more than 2,000 pieces of various sizes, stitched together with hundreds of meters of golden wire, thus symbolising the high social status of the deceased. According to Taoist doctrines of the time, jade had the power to preserve the body from decay, allowing the survival of the soul. From this belief derived the centuries‐long habit to sew around the body of the deceased a real suit of jade, whose preparation engaged experienced craftsmen for many years. The specimen on display is one of the most beautiful among the almost forty found so far. The Tang Dynasty (581‐907) put an end to four centuries of strife, bringing back a period of political stability and social harmony unequalled for generations. For the first time, the population was guaranteed a high standard of living, and the styles, the artistic and cultural skills, the trends and the quirks that characterized this period remained in vogue for long and forged the aesthetic imprint of the country of the years ahead. The Tang dynasty opened up to a glorious era, a ʺgolden ageʺ that made China the cultural centre of Eastern Asia with echoes reached the Mediterranean. Fascinated by all that was foreign, the cosmopolitan China of the Tang fed this attraction by importing through the Silk Road an endless variety of goods from all over the world. At the same time, goods carried ideas, knowledge and religious beliefs. It was by then that Buddhism entered China. This is all clearly shown in the exhibition: the common gold and silver tools decorated with acanthus plants, grapes and floral motifs that attest to the influence of Western culture; vases covered with bright monochrome and polychrome lead glazing, known by the term sancai (three colors); copper mirrors typical of the Tang Dynasty decorated with branches of grapes, marine animals, dragons, clouds, symbols of good hope; red ceramic sculptures of female figures with clothing showing a markedly Central Asian style. Sculptures of foreigners or ʺbarbariansʺ were frequently placed among the funerary statuettes under the Tang Dynasty, thus attesting to the cosmopolitan life of the time. The city teemed with foreigners, just passing by or rather living in especially reserved areas. They took part in the everyday life of the capital and influenced its culture with their costumes and exotic habits. We see sculptures of ʺbarbariansʺ with their typical double‐breasted clothes, open‐necked and cinched at the waist with a belt and high boots. Sculptures of camels, typical of the Tang period, were associated by popular imagination to the intense traffic along the Silk Road. It’s there that the most cosmopolitan empire in the history of China used to import goods and export its most coveted products: silk and ceramics. We showcase different examples of camels, yellow, hand‐painted ceramics and, in particular, the ʺStatuette of barbarian with camelʺ, a three‐color ceramic whose delicate realism is accentuated by the inclination of the head of the animal. Also the depiction of horses reached levels of unprecedented naturalism during the Tang period, as shown by the finds on display. In 667, an imperial edict decreed that riding was exclusively reserved to the aristocracy and senior officials, thus becoming the prerogative of the nobility. The sculptures on display testify to the intense passion of the Tang for foreign horses, symbol of the military power and the opulence of the aristocracy. It was essential to undertake war campaigns but also indispensable for polo matches and hunting. The examples displayed in the exhibition illustrate this ideal of beauty and strength, even though forced on rectangular bases and deprived of tail and mane. Among the figures on horseback, there is also a ʺfemale statuetteʺ bearing witness to the freedom women enjoyed under the Tang and to the trend in vogue at that time. All this conveys the dynamism and the exuberance of the Tang era, which interpreted the novelties coming from the West by adapting them to the taste and the uses of China.