Illustrated Bible Survey

An Introduction

Ed Hindson and Elmer L. Towns

Uncorrected Galley

N a s h v i l l e , Te n n e s s e e

Illustrated Bible Survey

Copyright © 2013 by Ed Hindson and Knowing Jesus Ministries

All rights reserved.

ISBN: 978-1-4336-8221-6

Published by B&H Publishing Group

Nashville, Tennessee

Dewey Decimal Classification: 200.07

Subject Heading: BIBLE—STUDY AND TEACHING

Unless noted otherwise, Scripture quotations are from the Holman Christian Standard

Bible ® Copyright © 1999, 2000, 2002, 2003, 2009 by Holman Bible Publishers. Used by

permission.

Scripture quotations marked GNT are taken from the Good News Translation® (Today’s

English Version, Second Edition). Copyright © 1992 American Bible Society. All rights

reserved.

Scripture citations marked NASB are from the New American Standard Bible. ©The

Lockman Foundation, 1960, 1962, 1968, 1971, 1973, 1975, 1977. Used by permission.

Scripture quotations marked NIV are taken from THE HOLY BIBLE, NEW

INTERNATIONAL VERSION®, NIV® Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica,

Inc.™ Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide.

Scripture quotations marked NIV 1984 are taken from THE HOLY BIBLE, NEW

INTERNATIONAL VERSION®, NIV® Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984 by Biblica, Inc.™

Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide.

Scripture marked NKJV are taken from the New King James Version. Copyright © 1982

by Thomas Nelson, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Scripture marked NLT are taken from the Holy Bible, New Living Translation, copyright

1996. Used by permission of Tyndale House Publishers, Inc., Wheaton, Illinois 60189. All

rights reserved.

Image credits are on page 607. At time of publication, all efforts had been made to determine proper credit. Please contact B&H if any are inaccurate.

Printed in the United States of America

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 • 18 17 16 15 14 13

RRD

Dedication

To the more than 100,000 students

we have been privileged to teach

at Liberty University

over the past 40 years.

May God use you to change the

world in your generation.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

List of Maps . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . vii

List of Abbreviations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . viii

Contributors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ix

Preface . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . xi

1.How We Got the Bible . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

2.How to Read the Bible . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

3.Old Testament Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

4.Genesis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

5.Exodus . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47

6.Leviticus . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 61

7.Numbers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 71

8.Deuteronomy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 81

9.Joshua . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 91

10.Judges and Ruth . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 103

11. 1 and 2 Samuel . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 117

12.Kings and Chronicles . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 127

13.Ezra and Nehemiah . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 147

14.Esther . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 163

15.Job . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 173

16.Psalms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 183

17.Proverbs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 193

18.Ecclesiastes and Song of Songs . . . . . . . . . . . . . 203

19.Isaiah . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 215

20.Jeremiah and Lamentations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 231

21.Ezekiel . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 247

22.Daniel . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 259

23.Minor Prophets, Part 1 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 275

24.Minor Prophets, Part 2 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 305

25.The History Between the Testaments. . . . . . . . . . . 331

Contributors

v

vi

Illustrated Bible Survey

26.New Testament Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 339

27.Matthew . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 349

28.Mark . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 361

29.Luke . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 371

30.John . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 383

31.The Book of Acts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 395

32.Romans . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 411

33.1 and 2 Corinthians . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 423

34.Galatians . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 439

35.Ephesians . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 451

36.Philippians . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 463

37.Colossians and Philemon . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 469

38.1 and 2 Thessalonians . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 481

39.1 and 2 Timothy and Titus . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 493

40.Hebrews . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 509

41.James . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 521

42.1 and 2 Peter and Jude . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 529

43.1, 2, and 3 John . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 543

44.Revelation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 555

Name Index . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 571

Subject Index . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 574

Scripture Index . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 586

Image Credits . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 607

List of Maps

The Migration of Abraham . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42

The Route of the Exodus . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51

Egypt: Land of Bondage . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 53

The Journey from Kadesh-barnea to the Plains of Moab . . 78

The Tribal Allotments of Israel . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 97

Location of the Judges throughout Israel . . . . . . . . . 106

Kingdom of David and Solomon . . . . . . . . . . . . . 134

The Kingdoms of Israel and Judah . . . . . . . . . . . . 136

The Return of Jewish Exiles to Judah . . . . . . . . . . 148

The Persian Empire . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 165

The Rise of the Neo-Babylonian Empire . . . . . . . . . 232

Jewish Exiles in Babylonia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 243

World Powers of the Sixth Century . . . . . . . . . . . . 252

Prophets of the Eighth Century . . . . . . . . . . . . . 301

The Passion Week in Jerusalem . . . . . . . . . . . . . 389

Expansion of the Early Church in Palestine . . . . . . . 401

The First Missionary Journey of Paul . . . . . . . . . . 403

The Second Missionary Journey of Paul . . . . . . . . . 405

The Third Missionary Journey of Paul . . . . . . . . . . 406

Galatia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 440

Paul’s Conversion and Early Ministry . . . . . . . . . . 445

Crete . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 504

The Seven Churches of Asia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 557

vii

List of Abbreviations

AB

ANET

AUSS

BAR

BCOT

BECNT

BKC

BKCNT

CBC

DSB

EBC

FOTL

HNTC

ICC

ISBE

ITC

IVP

JSOT

JSOTSup

KJBC

NAC

NCBC

NT

NICNT

NICOT

NIGTC

NIVAC

NT

NTC

OT

OTL

OTSB

PNTC

SJT

TNTC

TOTC

TWOT

VT

WBC WEC

ZECNT

ZIBBC

Anchor Bible

Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament

Andrews University Seminary Studies

Biblical Archaeology Review

Baker Commentary on the Old Testament

Baker Evangelical Commentary on the New Testament

Bible Knowledge Commentary

Bible Knowledge Commentary: New Testament

Cambridge Bible Commentary

The Daily Study Bible

The Expositor’s Bible Commentary

Forms of the Old Testament Literature

Holman New Testament Commentary

International Critical Commentary

International Standard Bible Encyclopedia

International Theological Commentary

InterVarsity Press

Journal for the Study of the Old Testament

Journal for the Study of the Old Testament: Supplement Series

King James Bible Commentary

New American Commentary

New Century Bible Commentary

New Testament

New International Commentary on the New Testament

New International Commentary on the Old Testament

New International Greek Testament Commentary

New International Application Commentary

New Testament

New Testament Commentary (Baker Academic)

Old Testament

Old Testament Library

Old Testament Study Bible

Pelican New Testament Commentaries

Scottish Journal of Theology

Tyndale New Testament Commentary

Tyndale Old Testament Commentary

Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament

Vetus Testamentum

Word Biblical Commentary

Wycliffe Exegetical Commentary

Zondervan Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament

Zondervan Illustrated Background Commentary

viii

Contributors

Authors

Edward E. Hindson (Th.D., Trinity Graduate School; D.Min., Westminster

Theological Seminary; D.Litt et Phil., University of South Africa; F.I.B.A.,

Cambridge University) is the distinguished professor of religion and biblical

studies at Liberty University.

Elmer L. Towns (Th.M., Dallas Theological Seminary; D.Min., Fuller Theological

Seminary) is the distinguished professor of systematic theology and dean of

the School of Religion at Liberty University and dean of the Liberty Baptist

Theological Seminary.

Associate Editors

John Cartwright (M.Div., Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary; Ed.D. student at

The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary) is department chair, School of

Religion, LU Online at Liberty University.

Gabriel Etzel (D.Min., Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary, Ph.D. student at The

Southern Baptist Theological Seminary) is associate dean, School of Religion at

Liberty University.

Ben Gutierrez (Ph.D., Regent University) is professor of religion and administrative

dean for undergraduate programs at Liberty University.

Wayne Patton (M.Div., Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary; D.Min. student at

Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary) is associate dean, College of General

Studies at Liberty University.

Editorial Advisors

James A. Borland (Th.D., Grace Theological Seminary)

Professor of New Testament and Theology

Wayne A. Brindle (Th.D., Dallas Theological Seminary)

Professor of Biblical Studies and Greek

David A. Croteau (Ph.D., Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary)

Professor of New Testament and Greek

Alan Fuhr, Jr. (Ph.D., Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary)

Assistant Professor of Biblical Studies

ix

x

Illustrated Bible Survey

Harvey Hartman (Th.D., Grace Theological Seminary)

Professor of Biblical Studies

Gaylen P. Leverett (Ph.D., Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary)

Associate Professor of Theology

Donald R. Love (Th.M., Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary)

Assistant Professor of Biblical Studies

Randall Price (Ph.D., University of Texas at Austin)

Distinguished Research Professor and Executive Director,

Center for Judaic Studies

Michael J. Smith (Ph.D., Dallas Theological Seminary)

Associate Professor of Biblical Studies

Gary Yates (Ph.D., Dallas Theological Seminary)

Associate Professor of Old Testament and Hebrew

Preface

T

he Bible is the most important book ever written. It contains sixty-six

individual books from Genesis to Revelation. These were collected over

1,500 years into one grand volume that we call the Word of God. Christians

accept the Bible as uniquely inspired of God and, therefore, authoritative

for our beliefs and practices. The Bible itself proclaims that its authors were

“moved by the Holy Spirit” so that “men spoke from God” (2 Pet 1:21).

We have taught Bible survey courses for a combined total of nearly one

hundred years at various institutions but mostly at Liberty University where

we have been privileged to serve together for over 30 years. We have taught

thousands of students from every walk of life, majoring in everything from

accounting to zoology—business, history, journalism, philosophy, psychology, nursing, premed, prelaw, religion, you name it. Our goal has always

been to challenge them academically, inspire them spiritually, and motivate

them effectively to discover and apply the great truths and practical wisdom of the Bible in providing them with a biblical basis for the Christian

worldview.

Introducing the basic content of the books of the Bible generally includes

the examination of their authorship, background, message, and application.

Our purpose is to provide a college-level textbook that is accessible to students and laymen alike. Therefore, we have left the more technical discussions of authorship and genre to seminary- and graduate-level introductions

such as B&H’s The World and the Word by Merrill, Rooker, and Grisanti and

also The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown by Köstenberger, Kellum, and

Quarles, which we highly recommend.

For us the Bible is not merely a combination of ancient documents, historical details, and religious information. It is the living Word of God that

still speaks to the minds, hearts, and souls of men and women today. It confronts our sin, exposes our selfishness, examines our motives, challenges

our presuppositions, calls us to repentance, asks us to believe its incredible

xi

xii

Illustrated Bible Survey

claims, stretches our faith, heals our hurts, blesses our hearts, and soothes

our souls.

Jesus spoke often of His confidence in the Bible with such phrases as

“the Scripture must be fulfilled” (John 13:18); “the Scripture cannot be broken” (John 10:35); “you will know the truth, and the truth will set you free”

(John 8:32); “I did not come to destroy [the Law or the Prophets] but to fulfill” (Matt 5:17); “man must not live on bread alone but on every word that

comes from the mouth of God” (Matt 4:4); “today . . . this Scripture has been

fulfilled” (Luke 4:21). Jesus read and quoted the Old Testament Hebrew

Scriptures with assurance that they were the Word of God. He also promised

His disciples that the Holy Spirit of truth will “guide you into all truth” and

“declare to you what is to come” (John 16:13). This promise was realized

when the Holy Spirit came upon the apostles enabling them to remember all

that Jesus said and taught (John 14:26).

Teaching the Bible is one of the great privileges and blessings of the

Christian life. We believe it is our greatest calling to proclaim, clarify, and

explain the biblical message. It is not our story; it is God’s story. It is the

story of His love and grace that has pursued human beings down through the

tunnel of time, through the halls of history and into the vast canyon of eternity. The Bible is a story of an infinite, yet personal Being who loves us with

an inexhaustible love that is expressed in His amazing grace which reaches

out to us time and time again.

We want to thank the editorial team of biblical scholars from Liberty

University and the Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary for their advice,

assistance, and encouragement in this endeavor. We also want to thank

Dr. Gary Smith who served as the external editor for B&H and Michael

Herbert, B.S. of Liberty University, who served as the managing editor of

the electronic file. It is our prayer that this survey of the Bible will enlighten

your mind and open your soul to the One who dared to say, “Everything

written about Me . . . must be fulfilled. Then He opened their minds to

understand the Scriptures” (Luke 24:44–45).

Ed Hindson and Elmer Towns

Liberty University in Virginia

Chapter 1

How We Got

the Bible

T

he Bible is a collection of sixty-six books that are recognized as

divinely inspired by the Christian church. They are divided into the Old

Testament (39 books) and the New Testament (27 books). Collectively these

books included law, history, poetry, wisdom, prophecy, narratives, biographies, personal letters, and apocalyptic visions. They introduce us to some

of the most amazing people who have ever lived: shepherds, farmers, patriarchs, kings, queens, prophets, priests, evangelists, disciples, teachers, and

most of all—the most unique person who ever lived—Jesus of Nazareth.

How We Got the Old Testament

God revealed His Word to ancient Israel over a thousand-year period

(ca. 1400–400 BC), and then scribes copied the biblical scrolls and manuscripts for more than a millennium after that. The process by which the Old

Testament books came to be recognized as the Word of God, and the history of how these books were preserved and handed down through the generations enhances our confidence in the credibility of the Old Testament as

inspired Scripture (2 Tim 3:16).

What Books Belong in the Old Testament?

The canon of Scripture refers to the list of books recognized as divinely

inspired and authoritative for faith and practice. Our word canon is derived

from the Hebrew qaneh and the Greek kanon, meaning a “reed” or a “measuring stick.” The term came to mean the standard by which a written work

was measured for inclusion in a certain body of literature. The books of the

Bible are not inspired because humans gave them canonical status. Rather,

the books were recognized as canonical by humans because they were

inspired by God. As Wegner explains, the books of the Old Testament “did

1

2

Illustrated Bible Survey

not receive their authority because they were placed in the canon; rather they

were recognized by the nation of Israel as having divine authority and were

therefore included in the canon.”1

The order and arrangement of the Hebrew canon is different from that

of our English Bibles. The Hebrew canon consists of three major sections,

the Law (Torah), the Prophets (Nevi’im), and the Writings (Kethuvim).

Collectively they are referred to as the Tanak (an acrostic built on the first

letters of these three divisions—TNK).

The Hebrew Canon

Law

Genesis

Exodus

Leviticus

Numbers

Deuteronomy

Prophets

Former Prophets

Latter Prophets

Joshua

Judges

1 and 2 Samuel

1 and 2 Kings

Isaiah

Jeremiah

Ezekiel

Minor Prophets

(Book of the 12)

Writings

Psalms

Job

Proverbs

Ruth

Song of Songs

Ecclesiastes

Lamentations

Esther

Daniel

Ezra

Nehemiah

Chronicles

The Septuagint (LXX), the Greek translation of the Old Testament, first

employed the fourfold division of the Old Testament into Pentateuch,

Historical Books, Poetical Books, and

Prophetic Books that is used in the

English Bible. The inclusion of historical

books within the prophetic section of the

Hebrew canon reflects their authorship

by the prophets. Daniel appears in the

Writings rather than the Prophets because

Daniel was not called to the office of

prophet even though he functioned as a

prophet from time to time. Chronicles at Jewish rabbi copying Hebrew Scripture.

the end of the canon provides a summary

How We Got the Bible 3

of the entire Old Testament story from Adam to Israel’s return from exile

though it was written from a priestly perspective.2

How Were the Old Testament Books Selected?

When Moses came down from Mount Sinai with the Commandments

God gave him, the people of Israel immediately recognized their divine

authority and promised to obey them as the words of the Lord (Exod 24:3–8).

The writings of Moses were stored at the central sanctuary because of their

special status as inspired Scripture (Exod 25:16, 21; Deut 10:1–2; 31:24–26).

In Deut 18:15–22, the Lord promised to raise up a succession of prophets

“like Moses” to speak His word for subsequent generations, and the pronouncements of these messengers of God would also be recognized as possessing divine authority.

When Was the Process Completed?

Jewish tradition affirmed that prophecy

ceased in Israel ca. 400 BC after the ministry of Malachi. First Maccabees 9:27 states,

“So there was great distress in Israel, such as

had not been since the time that the prophets ceased to appear among them.” Baruch

85:3 makes a similar claim, and the Jewish

Talmud states that the Holy Spirit departed

from Israel after the prophets Haggai,

Zechariah, and Malachi in the early postexilic period. While some questions remained

regarding some of the “writings” that were

already included in Scripture (e.g., Esther)

even until the Council of Jamnia in AD 90,

the evidence suggests that the Hebrew canon

was essentially completed and fixed by 300 A Torah scroll being held in its

BC. All of the canonical books of the Old wooden case at a celebration in

Jerusalem.

Testament, except for Esther, appear among

the copies of the Dead Sea Scrolls (250 BC–AD 70).3

How Does the New Testament View the Old Testament?

Jesus and the apostles accepted the inspiration of the Old Testament

Scriptures and often referred to or quoted them as authoritative. According

to Jesus, the words written by the human authors of Scripture were the

4

Illustrated Bible Survey

“command of God” and “God’s word” (Mark 7:8–13; cf. Matt 19:4–5). As

God’s Word every part of the Old Testament would be accomplished and

fulfilled (Matt 5:17–18; 26:54, 56; Luke 24:27, 44; John 7:38), and nothing

it predicted could be voided or annulled (Luke 16:17; John 10:35). Jesus

described the Old Testament canon as extending from Genesis to Chronicles

when speaking of the murders of Abel and the prophet Zechariah in Matt

23:34–35 and Luke 11:49–51 (cf. Gen 4:8 and 2 Chr 24:20–22).

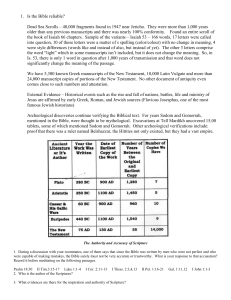

How Reliable Are the Old Testament Documents?

Though the earliest parts of the Old Testament were written ca. 1400

BC, the earliest existing Hebrew manuscripts for the Old Testament are the

more than 200 biblical manuscripts found at Qumran among the Dead Sea

Scrolls, dating from roughly 250 BC to AD 70. Prior to the discovery of

the Dead Sea Scrolls in 1947, the earliest extant Hebrew manuscripts of the

Old Testament dated 800–1000 years after the time of Christ. The earliest

complete copy of the Old Testament is Codex Leningrad, dating to near AD

1000.

Despite these significant chronological gaps between the original manuscripts and the earliest documents, one can have confidence that the original

message of the Hebrew Bible was faithfully preserved throughout its long

and complicated transmission process.

Scribal practices in the ancient Near East demonstrate the care and precision taken by members of that craft in copying important political and

religious texts. Israelite scribes who had a special reverence for the Scriptures

as the Word of God were careful when copying the biblical manuscripts.

As the earliest existing

Hebrew manuscripts, the Dead

Sea Scrolls are an important

witness to the textual integrity

of the OT. Many of the biblical

scrolls found at Qumran reflect

a text that closely resembles the

later Masoretic Text (MT), the

textual tradition represented in

the Hebrew Bible today. The

close similarity of the Isaiah

Scroll (1QIsab) found at Qumran A fragment from the Dead Sea Scrolls.

to later Masoretic manuscripts

of Isaiah reflects how carefully the scribes copied the text.

How We Got the Bible 5

After the close of the OT canon (ca. 300 BC) and the standardization of

the Hebrew text (first century AD), meticulous and careful scribal practices

ensured that the received text of the OT was handed down unchanged. A

special group of scribes called the Masoretes (AD 500–1000) played a vital

role in the transmission and preservation of the OT text. The Masoretes also

meticulously counted the letters, words, and verses in the text. For example,

the final Masorah at the end of Deuteronomy notes that there are 400,945

letters and 97,856 words in the Torah and that the middle word in the Torah

is found in Leviticus 10:16.

The Hebrew text on this collapsed stone from the

trumpeting place in Jerusalem reads, “to the place

of trumpeting to . . . .” This stone probably marked

the place where a trumpeter announced the beginning and end of the Sabbath every week.

The Gezer Calendar is believed

to be one of the oldest Hebrew

inscriptions found to date. The

inscription is on a limestone

tablet and dates from 925 BC.

The study of textual criticism is the science that enables scholars to

determine and establish the wording of the original text. The number of textual variants due to handwritten mistakes that affect the meaning of the text

are relatively few, and none of these variants change any major OT teaching

or Christian doctrine.4 Rather than undermining a person’s confidence in the

Scriptures, the textual criticism and transmission history of the Bible enables

everyone to see how accurately the Bible today reflects what God originally

communicated to His people in His Word. By contrast, no other documents

from the ancient world were as accurately copied, preserved, and transmitted

as the Old Testament Scriptures.

6

Illustrated Bible Survey

How We Got the New Testament

Which Books Belong in the New Testament?

The New Testament consists of twenty-seven books that were written

from about AD 45 to approximately AD 100. Some authors penned their

books, while other authors dictated the contents of a letter or narrative to an

assistant (i.e., a scribe). This assistant wrote down what was spoken, and the

author checked the document for accuracy. Apparently, Paul handwrote

some of his first letters (Gal 6:11), but his later letters, which were dictated,

ended with his handwritten salutation to authenticate them (2 Thess 3:17;

Col 4:18; also see 1 Pet 4:12). The books of the New Testament were written

on leather scrolls and papyrus sheets. These books included the four Gospels,

the Acts of the Apostles, Paul’s Letters, the General Epistles, and the

Revelation (or Apocalypse).

These books were circulated independently at first, not as a collection. Itinerant

preachers such as the apostle Matthew may

have stayed in the homes of rich believers

who had libraries and servants to be their personal scribes. Matthew may have allowed a

scribe to copy his Gospel. Hence, the Gospel

of Matthew was circulated widely as he traveled from church to church. Paul instructed

that some of his letters be circulated (Col

4:16). We do not know if the actual letter

(called an “autograph”) was circulated to

various churches or if copies were made by

scribes to be circulated. Regardless, copies

were eventually gathered into collections

(apparently there were collections of Paul’s

letters, see 2 Pet 3:16). They were copied

into codices which are similar to modernday books, with the pages sewn together Greek papyrus.

on one side to form a binding. In this form

the documents were easier to read. Leather and scrolls were harder to use

because the entire book had to be unrolled to find a passage. Also, papyrus

sheets cracked if rolled into a scroll; hence, the flat papyrus pages were sewn

into a book. The codex collection was called in Latin Ta Bibla, the words we

use to designate our Bible.

How We Got the Bible 7

The Greek Language

The New Testament books were written in Greek that was different

from the classical Greek of the philosophers. Archaeological excavations

have uncovered thousands of parchments of “common language Greek,”

verifying that God chose the language of common people (Koine Greek) to

­communicate His revelation. God chose an expressive language to communicate the minute colors and interpretations of His doctrine. Still others feel

God prepared Greeks with their intricate language, allowed them to conquer

the world, used them to institute their tongue as the universal “trade language,” then inspired men of God to write the New Testament in common

Greek for the common people who attended the newly formed churches.

This made the Word of God immediately accessible to everyone.

The Manuscript Evidence

The original manuscripts, called “autographs,” of the books of the Bible,

were lost, mostly during the persecution of the early church. Roman emperors felt that if they could destroy the church’s literature, they could eliminate

Christianity. Others were

lost due to wear and tear.

The fact that some early

churches did not keep these

autographs but made copies and used them demonstrates that they were more

concerned with the message

than the vehicle of the message. God in His wisdom

allowed the autographs to

vanish. Like the relics from This is the oldest complete Coptic Psalter, representing

the Holy Land, they would one of the most important ancient biblical texts. It dates

to the fourth or fifth century and was found buried in a

have been venerated and cemetery.

worshipped. Surely bibliolatry (worship of the Bible)

would have replaced worship of God.

While some may have difficulty with the idea of not having an original

manuscript, scholars who work with the nonbiblical documents of antiquities likewise do not have access to those originals. When considering the

manuscript evidence, it should be remembered there are close to 5,000 Greek

manuscripts and an additional 13,000 manuscript copies of portions of the

8

Illustrated Bible Survey

New Testament. This does not include 8,000 copies of the Latin Vulgate and

more than 1,000 copies of other early versions of the Bible. These figures

take on even more significance when compared to statistics of other early

writings.5

THE NEW TESTAMENT CANON

Some writers have supposed that Christians didn’t discuss a canon for

New Testament books until a few centuries after the life of Jesus. However,

because of the presence of the heretic Marcion (died ca. 160), this is unlikely.

Marcion was a bishop in the church who had a negative view about the God

presented in the Old Testament. He rejected the Old Testament and had a

severely shortened New Testament canon, consisting of only the Gospel of

Luke and ten of Paul’s letters. However, even these were edited to remove

as much Jewish influence as possible. The church excommunicated Marcion

and rejected his teachings and canon.

Another heretical movement, Gnosticism, developed in the second century. In general this group believed that salvation was found in attaining

“special knowledge.” The Gnostics had their own set of writings defending their beliefs and practices. Included in their writings are false Gospels

(for example, the Gospel of Thomas). The Gnostics and Marcion raised the

question as to which books were genuine and authoritative for Christians.6

Metzger concludes: “All in all, the role played by Gnostics in the development of the canon was chiefly that of provoking a reaction among members

of the Great Church so as to ascertain still more clearly which books and

epistles conveyed the true teaching of the Gospels.”7

TESTS OF CANONICITY

The process in which the canon was formed is rather complicated.

However, some offer the following three tests for a book to be considered

part of the canon: (1) apostolicity; (2) rule of faith; and (3) consensus.

The test of apostolicity means that a book must be written by an apostle

or one connected to an apostle. When applied to the New Testament, most

books automatically meet this requirement (those written by Matthew, John,

Paul, and Peter). Mark and Luke were both associates of Paul. James was a

half brother of Jesus, and Jude is either an apostle or the half brother of Jesus.

The only book that has much difficulty with this criterion is Hebrews. Many

in the early church believed Paul wrote Hebrews, but many New Testament

scholars today suggest it was written by Luke. If we don’t know who wrote

it, how can we connect it to the canon? Hebrews 13:23a says, “Be aware that

How We Got the Bible 9

our brother Timothy has been released.” Whoever the author of Hebrews

was, this reference places him within the Pauline circle.8

The rule of faith refers to the conformity between the book and orthodoxy. Orthodoxy refers to “right doctrine.” Therefore, the document had

to be consistent with Christian truth as the standard that was recognized

throughout Christian churches (e.g., in Corinth, Ephesus, Philippi, etc.). If a

document supported heretical teachings, then it was rejected.

Finally, consensus refers to the widespread and continuous use of a

document by the churches.9 At first there was not complete agreement—not

because a particular book was questioned, but not all books were universally

known. However, the books that were included had widespread acceptance.

Because the Holy Spirit breathed His life into a book by the process of inspiration (2 Tim 3:16), then the Holy Spirit that indwelt individual believers

(1 Cor 6:19–20), and the Holy Spirit that indwelt churches (1 Cor 3:16),

gave a unified consensus that a book was authoritative from God.

Applying these criteria to the books contained within the New Testament,

and those that were left out, shows the consistency of the canon as it was

handed down. Some “Gospels” have been found in recent years and have

raised quite a stir, for example, the Gospel of Thomas and the Gospel of

Judas. Why aren’t these “Gospels” considered authoritative for Christians?

First, these Gospels cannot be definitively linked to apostles, even though

apostles are named in the titles.10 Second, some heretical teachings in each

document contradict the teachings of Scripture. Third, neither of these documents was used either universally or continuously by the church.11 Therefore,

they each fail at all three criteria.

The New Testament that Christians use today has a long, rich history.

The original copies were written almost 2,000 years ago and were copied for

over 1,000 years by hand. All the books in the New Testament can be connected to an apostle, have content consistent with sound doctrine, and were

used widely throughout the church. The New Testament was translated into

many languages early in church history. Wycliffe and Tyndale were early

translators of the Bible into English, culminating in the King James Version

and many contemporary versions that now exist for the edification of the

body of Christ.

Altogether the Old and New Testament manuscripts, copies, and translations have stood the test of time. The Bible is God’s Book, written to reveal

Him and His message of salvation. God has preserved His Word over the

centuries to speak to our hearts today. As you read the Bible, let Him speak

10

Illustrated Bible Survey

to you. His words will challenge your thinking, stretch your faith, inform

your mind, bless your heart, and stir your soul.

For Further Reading

Beckwith, Roger. The Old Testament Canon of the New Testament Church: And

Its Background in Early Judaism. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1985.

Bruce, F. F. The Canon of Scripture. Downers Grove, IL: IVP, 1988.

Geisler, Norman, and W. Nix. A General Introduction to the Bible. Chicago:

Moody Press, 1986.

Kaiser, Walter C., Jr. The Old Testament Documents: Are They Reliable and

Relevant? Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2001.

Merrill, Eugene H. “The Canonicity of the Old Testament.” In The World and the

Word: An Introduction to the Old Testament. Nashville: B&H, 2011.

Rooker, Mark F. “The Transmission and Textual Criticism of the Bible.” In The

World and the Word: An Introduction to the Old Testament. Nashville: B&H,

2011.

Wegner, Paul D. A Student’s Guide to Textual Criticism of the Bible: Its History,

Methods and Results. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2006.

Study Questions

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

What does the term canon mean in relation to biblical books?

What is the threefold division of the Hebrew Bible?

What is the function and purpose of textual criticism?

How reliable are the Old Testament documents?

In which language are the books of the New Testament written?

How does the relation of the apostles to the New Testament

books influence their credibility?

NOTES

1. Paul D. Wegner, The Journey from Texts to Translations: The Origin and Development

of the Bible (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 1999), 101.

2. The word Apocrypha means “hidden books” and was first used with reference to these

works by Jerome c. AD 400. The exact meaning of this term when applied to these books

is unclear but implies their biblical authority was doubtful. Thus, they are not included in

Protestant versions of the Bible.

3. In the twenty-four-book canon, the Minor Prophets are a single book (“The Book of

the 12”), and 1–2 Samuel, 1–2 Kings, 1–2 Chronicles, and Ezra-Nehemiah are viewed as one

book each. Josephus arrived at a total of twenty-two books by also viewing Judges-Ruth and

Jeremiah-Lamentations as single books.

How We Got the Bible 11

4. Mark. F. Rooker, “The Transmission and Textual Criticism of the Bible,” in Eugene H.

Merrill, Mark F. Rooker, and Michael A. Grisanti, The World and the Word: An Introduction

to the Old Testament (Nashville: B&H, 2011), 109.

5. Josh McDowell, Evidence That Demands a Verdict (San Bernardino, CA: Campus Crusade

for Christ International, 1972), 48.

6. F. F. Bruce, The Canon of Scripture (Downers Grove: InterVarsity, 1988), 153.

7. Bruce M. Metzger, The Canon of the New Testament (New York: Oxford University

Press, 1987), 90.

8. For more on the authorship of Hebrews, see the chapter on Hebrews.

9. Also referred to as universality or catholicity.

10. See Andreas J. Köstenberger and Michael J. Kruger, The Heresy of Orthodoxy: How

Contemporary Culture’s Fascination with Diversity Has Reshaped Our Understanding of

Early Christianity (Wheaton: Crossway, 2010), esp. 151ff.

11. See Nicholas Perrin, Thomas: The Other Gospel (Louisville: Westminster, 2007).