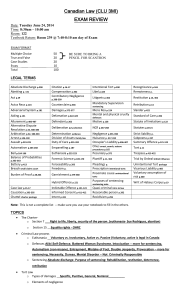

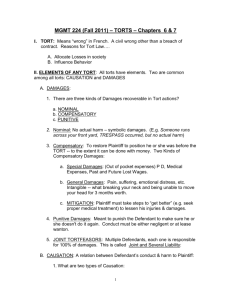

OVERVIEW

advertisement