Printable Version - Concordia University Wisconsin

advertisement

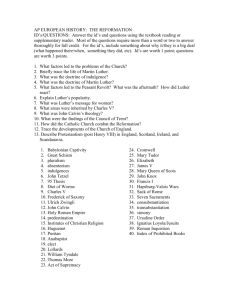

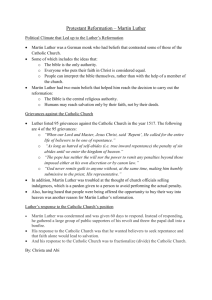

Historical Background of the Reformation 500 The year 1517 has been regarded as a pivotal moment in history. In April of that year Martin Luther penned 95 theses to protest the sale of indulgences in Saxony. Within months, contrary to Luther’s intentions, these theses had been printed and widely distributed, provoking a storm of controversy that started in Germany and spread throughout Europe. The Reformation had begun. “Few periods in the long history of Europe have had such a momentous impact upon the western world as the four decades lying between the years 1517 and 1559. It began when a very personal matter, Luther’s struggle for a right relationship to God, became a popular cause. Its end was marked by an auspicious public event, for Europe entered one of its rare interludes of peace.”1 The Reformation, then, was a significant event in the history of Christianity, in the history of Europe, and the history of Western Civilization. In its simplest terms, the Reformation was an attempt to correct beliefs and practices that the reformers argued had been added by the works of men over the course of centuries, leading people away from the Scriptures and salvation bought by the blood of Christ. According to the reformers, traditions, pronouncements of popes, and good works had supplanted God’s saving mercy through Christ; reason dominated faith and caused men to trust in their own efforts to earn salvation and to explain the workings of God; and works of theology and philosophy were more highly regarded than the saving message of Gospel. These practices, and criticisms of them, had been evident long before the 16th century. Attempts at reform had occurred repeatedly but had never succeeded in gaining any traction. Reforming an institution as large and as established as the Church was a very difficult task indeed. A combination of factors at the beginning of the 16th century paved the way for a reform movement. Social, political and economic changes, as well as cultural and intellectual trends, led to the development of a more literate laity who had increasing expectations of the clergy, expectations that neither individual priests nor the institution of the Church were equipped to meet. The Renaissance had brought a rebirth of classical culture that had promoted a renewed emphasis upon sources, a new kind of education, an emphasis upon the individual and the development of moral character, and a shift in worldview. All of this laid the foundation for the Reformation. The word “Reformation” is somewhat of a misnomer. Martin Luther initially set out to reform the Church and to bring it back to its Scriptural roots, but the end result of his movement for reform was the fracturing of the Catholic Church. The Reformation Era, the period between 1517 and 1648, witnessed multiple reformations, the foremost among which were the ones led by Luther, John Calvin, and the Catholic Church that was spearheaded by the newly formed 1 Lewis W. Spitz, The Protestant Reformation, 1517-1559 (Harper & Row, 1985), p. 1. Society of Jesus. Currents of Protestant reform were felt all over Europe, but principally in the Holy Roman Empire, Switzerland, England, France, Eastern Europe and Scandinavia. Catholic reform centered on Italy, Spain, France and parts of the Holy Roman Empire. Despite the multiplicity of religious movements during this era, Martin Luther nevertheless remains the face of the Reformation. It is for this reason that we mark the start of the Reformation with the posting of Luther’s 95 Theses in 1517. One could argue, though, that the decisive moment came at the Diet of Worms in 1521. Asked to recant the things he had written that both the Church hierarchy and the universal authority of the Holy Roman emperor deemed errors (one step away from heresy), Martin Luther responded thus: “Since your most serene majesty and your high mightinesses require of me a simple, clear and direct answer, I will give one, and it is this: I can not submit my faith either to the pope or to the council, because it is as clear as noonday that they have fallen into error and even into glaring inconsistency with themselves. If, then, I am not convinced by proof from Holy Scripture, or by cogent reasons, if I am not satisfied by the very text I have cited, and if my judgment is not in this way brought into subjection to God’s word, I neither can nor will retract anything; for it can not be right for a Christian to speak against his [conscience]. I stand here and can say no more. God help me. Amen.”2 These words were important enough to be included in Bartleby’s book of most famous orations of the world, and rightly so. This moment arguably “augured one of the most momentous changes in the history of Europe, and one of the most significant in the history of the church.”3 It was more than simply a “new theological system” or a “new way of thinking theologically.” Luther’s theology was shaped by the “doctrine of salvation by God’s grace alone, received as a gift through faith and without dependence upon human merit.”4 This became the standard against which the theology, practices and structures of the Catholic Church would be measured. Against this standard, the Church, the reformers argued, had erred and had deviated from the faith of the early Church. William Jennings Bryan, ed. The World’s Famous Orations. (New York: Funk and Wagnalls, 1906; New York: Bartleby.com, 2003). www.bartleby.com/268/ at http://www.bartleby.com/268/7/8.html. Accessed 29 January 2016. Spitz gives Luther’s answer in a slight different translation: “Since then your serene majesty and your lordships seek a simple answer, I will give it in this manner, neither horned nor toothed: Unless I am convinced by the testimony of the Scriptures or by clear reason (for I do not trust either rin the pope or in councils alone, since it is well known that they have often erred and contradicted themselves), I am bound by the Scriptures I have quoted and my conscience is captive to the Word of God. I cannot and I will not retract anything, since it is neither safe nor right to go against conscience. I cannot do otherwise, here I stand, may God help me, amen.” (Spitz, Protestant Reformation, p. 75). 3 Mark A. Noll, Turning Points: Decisive Moments in the History of Christianity, 3rd ed. (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2012), p. 146. 4 Lewis W. Spitz, The Renaissance and Reformation Movements, rev. ed., Vol. II: The Reformation (St. Louis, MO: Concordia Publishing House, 1987), pp. 332, 333. 2 This was the decisive point. At Worms Luther had declared that his conscience was captive to the Word of God, which was the “living, active voice of Scripture.” Luther felt that Scripture taught clearly “truths about human nature, the way of salvation, and the Christian life,” truths that had been forgotten, neglected, or rejected by the Church.5 In stressing the authority of Scripture over and above all earthly authorities (popes, councils, rulers), Luther was not only stressing an individual’s faith but the individuality of each person, a key tenet of the modern world view. In another sense, however, Luther was echoing the words of Augustine nearly a thousand years before: “Since we were too weak to find the truth by pure reason, and for that cause we needed the authority of Holy Writ, I now began to believe that in no wise would you have given such surpassing authority throughout the whole world to that Scripture, unless you wished that both through it you be believed in and through it you be sought.” The authority of and in Scripture to Augustine seemed “all the more venerable and worthy of inviolable faith, because they were easy for everyone to read and yet safeguarded the dignity of their hidden truth within a deeper meaning.”6 Truth was found in Scripture, and the Truth that was to be found there was God’s grace and mercy expressed through the love of Jesus Christ and the continual working of the Holy Spirit. Aside from the political, social, economic, intellectual, and cultural importance of the Reformation, the real significance of the Reformation was to turn the focus from human actions and intentions to Jesus Christ, who won salvation for humanity through God’s grace and mercy. The essential meaning of the Reformation—the saving message of the Gospel—did not end with Luther. The Reformation started nearly 500 years ago, but the work of the Reformation carries on to the present day. It can be found in churches, schools, and communities. It is expressed in a variety of ways by individuals here and around the world. Our commemoration of the 500th anniversary of the Reformation is intended not only as an opportunity to remember the work of Luther, but also to marvel that the legacy of the Reformation still endures. 5 6 Noll, Turning Points, p. 146. Augustine, The Confessions, trans. John K. Ryan (New York: Doubleday, 1960), pp. 139, 140. The Reformation & Political Events to 1555 1517 1518 1519 1520 1521 1521-1525 1522/23 1523 1523-34 1524-25 1525 1526 1526-1529 1527 1529 1530 1531 1535-1538 1538 1542-1544 1544 1545 1546 1546-48 1547 1548 1552 1555 1556 1558 1559 Jubilee Indulgence: Leo X & Johann Tetzel Luther’s 95 Theses Heidelberg Disputation Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor & King of Spain Leipzig Debate: Luther & Carlstadt vs. Eck Exsurge Domine (Pope Leo X) Diet of Worms; Edict of Worms Luther takes refuge at the Wartburg 1st Hapbsburg-Valois War; Peace of Pavia Knights’ War. Luther’s return to Wittenberg Break with Erasmus Pope Clement VII (Medici) German Peasants’ Revolt Luther m. Katarina von Bora Diet of Speyer 2nd Hapsburg-Valois War; Peace of Cambrai Sack of Rome Diet of Speyer Turks besiege Vienna Charles crowned Holy Roman Emperor by pope Diet of Augsburg; Augsburg Confession; Melanchthon’s Apology for the Augsburg Confession Schmalkaldic League formed 3rd Hapsburg-Valois War Catholic League formed 4th Hapsburg-Valois War Charles V makes peace with Francis I (again) Diet of Speyer Schmalkaldic Articles Charles V makes peace with the Turks (again) Council of Trent opens Death of Luther Schmalkaldic Wars Diet of Augsburg Augsburg Interim Peace of Passau Peace of Augsburg Abdication of Charles V Death of Charles V Peace of Cateau-Cambresis The 16th-century Catholic Church 1480 1512-1517 1513-1521 1516 1522-1523 1523-1534 1524 1528 1532 1533 1534-1549 1540 1542 1545-1563 1550-1555 1555 1555-1559 1556 1559-1565 1564 1566-1572 1572-1585 1582 1585-1590 1591 1592-1605 Spanish Inquisition established as national institution 5th Lateran Council Leo X Oratory of Divine Love (Italy) Adrian VI Clement VII (Medici) Theatines Capuchins Somatians Barnabites Paul III (Farnese) Appointed papal reform commission in 1537 (9 cardinals) that presented him with Counsel . . . Concerning the Reform of the Church Society of Jesus (Jesuits) recognized by the pope Inquisition expanded to all of Christendom Council of Trent Julius III Marcellus II Paul IV (Caraffa) Embodied spirit of the Counter-Reformation Began repressive part of Counter-Reformation Death of Ignatius Loyola Pius IV Professio fidei tridentinae Pius V Gregory XIII Death of St. Theresa of Avila (Spanish mystic) Sixtus V Death of St. John of the Cross (Spanish mystic) Clement VIII REFORMATION EVENTS: FRANCE, ENGLAND AND SPAIN 1558 1559 1560s 1562 1563 1567 1568 1570 1571 1572 1573 1579 1580 1583 1584 1584-1585 1585 1586 1587 1588 1589 1589-1598 1593 1594 1595 1596 1598 1603 1609 1610 1611 Elizabeth inherited Ireland John Knox published “First Blast of the Trumpet against the Monstrous Regiment of Women” Death of Henri II of France Revolts in the Netherlands against Spain Religious Wars in France Catherine de’Medici issued Edict of Toleration in France Parliament reaffirmed Act of Uniformity; Vestiarian controversy in England; John Foxe published his Acts and Monuments Duke of Alba began reign of terror in Netherlands Mary Queen of Scots fled to England Papal bull excommunicated Queen Elizabeth of England Catherine de’Medici isued Edict of St.-Germain Battle of Lepanto (first European victory against Ottomans fleet) Treaty of Blois Francis Drake unleashed on the seas Presbyterianism pressed for in England; Ridolfi Plot discovered in England St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre in France Francois Hotman published Francogallia Vindiciae contra tyrannos published Philip II claims Portugal Six Articles passed in England William of Orange assassinated War of the Three Henris in France Parliament passes law banishing Jesuits from England Spanish ambassador expelled from England Mary Queen of Scots executed in England Sir Francis Drake attacks Lisbon and Cadiz Philip sends Spanish Armada against England Henri III of France assassinated Wars of the Catholic League in France Richard Hooker publishes Laws of the Ecclesiastical Polity Irish revolts against England begin Lambeth Articles promulgated in England Spanish seize Calais Henri IV of France issues the Edict of Nantes Death of Elizabeth I; Accession of James I Truce between Spain and Dutch Henri IV of France assassinated King James Bible published