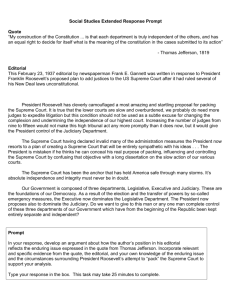

The Early Supreme Court Justices' Most Significant Opinion

advertisement