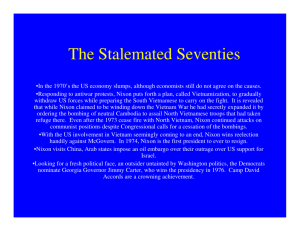

The Stalemated Seventies

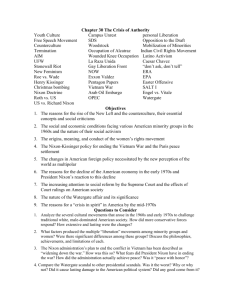

advertisement