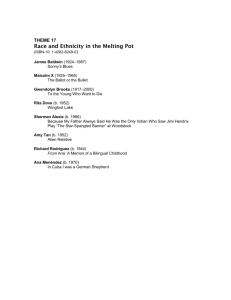

Sherman Alexie's Reservation: Relocating the Center of Indian Identity

advertisement