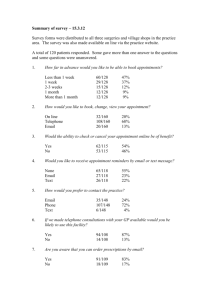

Patient Scheduling

advertisement