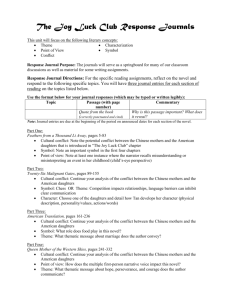

Ethical Argument Essay

advertisement