Exclusionary Rule Hanging On By a Thread

13, February, 2009 Volume 155, No. 31

Exclusionary Rule Hanging

On By a Thread

Let me break the bad news to criminal-defense attorneys. To paraphrase Mark Twain, the reports of the imminent death of the

Fourth Amendment's exclusionary rule may not be all that exaggerated. Two recent U.S. Supreme Court opinions and a decision from the 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals do not bode well for the future of this long-standing doctrine.

The first U.S. Supreme Court case on this subject was decided in 1914.

In Weeks v. U.S., 232 U.S. 383 (1914), the court held that evidence seized by federal officers in violation of the Fourth Amendment could not be used by prosecutors at a federal criminal trial. The Warren

Court expanded the rule to state criminal trials in 1961 in Mapp v. Ohio,

367 U.S. 643.

Beginning with the Burger Court in 1969, the Supreme Court has for the last 40 years found ways to limit and restrict the rule. The court has consistently refused to extend the use of the rule to proceedings other than criminal trials. See, e.g., U.S. v. Calandra, 414 U.S. 338 (1974) (inapplicable to grand jury proceedings); U.S. v. Janis, 428 U.S. 433 (1976) (inapplicable to civil trials); I.N.S. v.

Lopez-Mendoza, 468 U.S. 1032 (1984) (inapplicable to civil deportation hearings); Penn. Board of

Probation and Parole v. Scott, 524 U.S. 357 (1998) (inapplicable to parole revocation hearing). In addition, the court has prohibited state court defendants from raising Fourth Amendment exclusionary rule claims in federal habeas corpus. Stone v. Powell, 428 U.S. 465 (1976).

And beginning in 1984, the court held that the mere fact that evidence was recovered as the result of a Fourth Amendment violation did not necessarily mean that the evidence had to be suppressed at a criminal trial. U.S. v. Leon, 468 U.S. 897 (1984). Leon held that illegally seized evidence should only be suppressed when the exclusion would serve as a deterrent to bad police behavior. Thus, when a judge erroneously issues a warrant which is not supported by probable cause, the evidence seized pursuant to the warrant will not be suppressed if the police can show ''good faith'' - i.e., they reasonably relied on the judge's assurance that there was probable cause. Moreover, there will be no suppression if the police reasonably rely on a statute allowing unreasonable searches. Illinois v.

Krull, 480 U.S. 340 (1987). And there will be no suppression if a clerical error by a court employee causes the police to arrest someone on an invalid warrant. Arizona v. Evans, 514 U.S. 1 (1995).

As you can see, limitations on the doctrine are nothing new. But the two recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions on the exclusionary rule are qualitatively different.

Three years ago the court faced the issue of whether police violation of the ''knock and announce'' rule should result in the suppression of evidence. Hudson v. Michigan, 547 U.S. 586 (2006). There is no question that a ''knock and announce'' violation - i.e., the police officers' failure to provide the occupant of a house with enough time to respond before entering the house to execute a warrant - is a Fourth Amendment violation. 514 U.S. 927 (1995). And the police in Hudson violated the Fourth

Amendment completely on their own; there was no ''good faith'' reliance on judges, the legislature, or court employees.

Yet in a 5-4 decision, the court nevertheless held that the evidence seized as a result of the Fourth

Amendment violation was admissible at a criminal trial.

The importance of the case lies not so much in the result as in the sweeping language of Justice

Antonin Scalia's majority opinion. Ignoring the long lineage of the Weeks-Mapp rule, the opinion states that ''Suppression of evidence ... has always been our last resort, not our first impulse.'' It noted that over the last few decades the court has rejected the ''expansive dicta'' in Mapp that suggested a wide scope for the exclusionary rule. The problems with the rule, the opinion says, are the ''substantial social costs'' connected with exclusion of evidence. The court states that for those criminal defendants trying to suppress evidence under Weeks-Mapp ''the jackpot [is] enormous: suppression of all evidence, amounting in many cases to a get-out-of-jail-free card.'' Thus, evidence should be suppressed only in those cases where the costs are outweighed by the benefits of deterring future bad police behavior.

Hudson marked the first time since Mapp that evidence seized pursuant to a Fourth Amendment violation caused solely by improper police behavior was found admissible at a criminal trial. Yet it would not be the last.

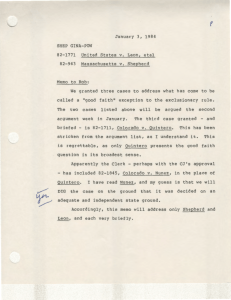

On Jan. 14, in yet another 5-4 decision with the identical lineup of justices as in Hudson, the

Supreme Court ratcheted up the standard of police misbehavior needed before evidence seized pursuant to a Fourth Amendment violation would be excluded at a criminal trial. The court held that the exclusionary rule would not apply to evidence seized pursuant to a Fourth Amendment violation if the police behavior could merely be characterized as ''isolated negligence'' rather than

''systemic error or reckless disregard'' of constitutional requirements. Herring v. U.S., 2009 U.S.

LEXIS 581. In Herring, the police arrested a man based on a warrant listed on a neighboring county's police database. The resulting search yielded drugs and a gun. It was later determined that the warrant had been recalled months before; it remained on the database solely through police negligence. The court held that the police error was not so ''objectively culpable'' as to trigger use of the exclusionary rule. Exclusion of evidence only ''serves to deter deliberate, reckless, or grossly negligent conduct, or in some circumstances recurring or systemic negligence.'' The court then held that the error in this case did not rise to this level.

As if defense attorneys needed more bad news, eight days after Herring the 7th Circuit chimed in with its own views on the exclusionary rule in U.S. v. Sims, 2009 U.S. App. LEXIS 1158 (decided Jan.

22). While conceding that the warrant in question technically violated the Particularity Clause of the Fourth Amendment, the court concluded that under the facts of the case it was - in the 7th

Circuit's language - a ''no harm, no foul'' situation. It thus refused to exclude the evidence.

The court's opinion, written by Judge Richard A. Posner , notes that the defendant could nevertheless bring a civil suit against the police for a constitutional tort. Posner goes on to predict:

''[T]he exclusionary rule is bound some day to give way to [civil remedies]. For the rule is too strict:

... the criminal [must be] let go to continue his career of criminality, even if the harm inflicted by the illegal search ... was slight in comparison to the harm to society of letting the defendant off scot free.''

So let's assume for the sake of argument the U.S. Supreme Court abolishes the exclusionary rule in the next few years. Where does this leave you, as a criminal defense attorney in Illinois state courts?

You may be in better shape than you might think.

Although the Warren Court did not mandate that state courts use the exclusionary rule until Mapp in 1961, Illinois courts recognized it as part of the state constitution way back in 1923. People v.

Brocamp, 307 Ill. 448 (1923). The independent power of the Illinois exclusionary rule was emphasized when the Illinois Supreme Court rejected the U.S. Supreme Court's limitation on the exclusionary rule in Illinois v. Krull, 480 U.S. 340 (1987). People v. Krueger, 175 Ill.2d 60 (1996). It is one of the few areas of search and seizure law where the Illinois Supreme Court does not meekly follow the U.S. Supreme Court in lockstep. See People v. Tisler, 103 Ill.2d 226, 245 (1984).

The lesson here is that Illinois defense attorneys should beginning planning for the day when there may no longer be a federal exclusionary rule. Illinois courts need to be continually reminded of why a state exclusionary rule is so necessary.

Forewarned is forearmed.