Celestial Fervor: A prelude to an Exhibition

advertisement

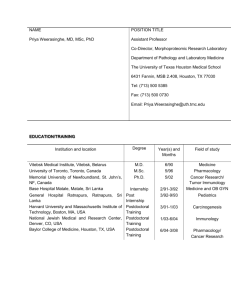

Celestial Fervor: A prelude to an Exhibition “I have enough guilt to make my own religion”- Jagath Weerasinghe By Anoli Perera Jagath Weerasinghe’s latest series of work titled ‘Celestial Fervor’ converges number of elements that determined some of his major art ideas interrogated within Weerasinghe’s overall art practice. Deeply politically conscious, socially sensitive being, his art cannot be summarized only within an art historical discourse without really venturing into a larger socio-political canvas that includes his own habitus, in an Bourdieuian sense. Therefore I would like to look at his art practice and emphasis on certain moments and events starting from his first major exhibition Kansawa (Anxiety) held at the Lionel Wednt Gallery in 1992, the first instance that put forth his political and art ideology evolved and matured during his post student days in Sri Lanka and American years as an graduate student. I am privileged as a writer to observe and articulate on Weerasinghe’s conceptions and thought processes to a great extent here because of my proximity to him as a fellow artist, a friend and a comrade in most post 1998 art activities ( interventions if one cares to call it) undertaken or initiated by him, and having the opportunity to engage in numerous discussions, disagreements and reconciliation of opinions with him . I am also not without knowledge how perilous such proximity can be to one’s perception and I will try to navigate my reading of his life and art (to Weerasinghe the division of life and art are intertwined and therefore it’s necessary to include both together) objectively within my own bias and convictions. A born to a dominant Marxist bourgeoisie father and a home making mother, growing up in an urbane middle class environment, Weerasinghe was probably early on exposed to the sympathies of the localized Marxist political ideology, its limitations and its contradictions when it came to class struggle, gender politics and social change. His identification with almost always with the ‘marginalized’ and the underprivileged (perhaps picked up from Marxist orientation at home), and his predilection for the subaltern is something that continues to underlies his political ideology. His restless years at Institute of Aesthetic Studies (now University of Visual and performing Arts) engaging in student politics, the rude awaking to the 1983 ethnicized riots, awareness of 1988-90 JVP/ government killing fields, and his own violent confrontations with authority, all these back-grounding an ethnic war, obviously marked his conscience deeply and led to realize the fundamental flaws in the Sri Lankan national psyche which boasts of its ‘Dharmishta-ness’, Buddhist-ness and Sinhala-ness, a threesome which often collapses into one composite and portent entity. I would like to read Weerasinghe’s work within three aphorisms. One is his own constant guilt for the pathologies that the society (which he is part of) has inflicted and continues to inflict on its people and his inability to intervene in it. The second is his realization of the magnitude of the destructive male power, the ‘chauvanism’ of ‘phallus’ that manifests in different forms and forces, from gender politics to ethnic politics, from religious fundamentalism and enhanced puritanical moralism to euphoria of war victory. The third is his own conviction that artist’s lived experience take centrality in his/her art, therefore artist cannot distance him/herself from its’ implications/ responsibility which makes art political as much as it is cultural. With this position on art, he makes it impossible for art to be amnesiac. In Weerasinghe’s own words “the bleeding heart at the centre of the painting is important to my story, even though it is at odds with its modernist construction.” i The most important socio-politically engaging and art historically important and interventionist exhibitions of Weerasinghe has been Kansawa and Yantra Gala and Round Pilgrimage. In his 1 exhibition Kansawa Weerasinghe put forward a difficult narration of an unwilling participant who became such for his inability to intervene in the assault that happened in July 1983 that scarred the memories of many Tamils. The works in the exhibition and other paintings done during this period emphasized the guilt of a society and its/his cathartic need for abreaction. Large number of paintings with imagery that symbolically as well as directly indicated fragmentation of a society depicted burnings, distorted human figures, images of photos which is reminiscent of a scattered family album in a burning house, all denoting pain and loss. The ‘long Necked Man’, a distorted human figure that recur in most of his paintings (throughout 1990s) in various contorted positions (in poses of pleading, defending, sprawled on the floor) projects a dual role in the overall exhibition: one is of the artist grappling with pain of his own guilt and the other is of the victims of 83 riots grappling with the pain of their predicament. While this duality opens up to the problematics of equating both pains at one level ignoring their specificities, it reveals the unrepentant silence of the perpetrating society and its unacknowledged responsibility for the violations inflicted, or the absence of an apology for its failure to protect its own citizens and Kansawa is Weerasinghe’s lonely effort of doing exactly what the Sri Lanka as a nation miserably failed to do. In this exhibition, the images of ‘broken stupa’s and ‘burning edifices of temples’ does not refer to archeological remains showing the desecration of a religion, but the religion’s desecration of the psyche of a society, and a betrayal of its core principle of non-violence. Kansawa also registers Weerasinghe’s initial grouses with the contemporary manifestations of institutionalized and politicized Buddhism and its links to the dangerous lineage of ethno chauvinism in the nationalism discourse. If Kansawa is about the disgust of ‘racism triumphing over humanity’ his exhibition Yantra Gala and the Round Pilgrimage (1997) revealed the pathology of a nation and its amnesiac status. More than in Kansawa, here Weerasinghe directly questions the ‘comforts’ one has of a paralytic nation amidst the presumably glorious Buddhist ethics (non effective in non-violence in the case of Sri Lanka). The exhibition included a series of paintings depicting a mother going from one camp to another in search of her disappeared son, which Weerasinghe equates to Atamasthana Wandanawa, the yearly pilgrimage of devout Buddhists, a journey they take going around worshipping eight religious sites designated as important and meritorious. The main installation consisted of a ‘centre stone’ that is normally enshrined inside pagodas of Buddhist temples, laid on a bed of unhusked rice scattered on the floor in an enclosure with the paintings (depicting mother in her search) on the surrounding walls. A flock of terracotta parrots were placed on the rice and broken statuettes of Buddha were placed on the centre stone. The rice scattered on the floor was mingled with pieces of paper with names of torture camps. The idea of arranging the installation in that manner was to make the viewer to go around the center stone reading the paintings; thereby he/she symbolically makes the pilgrimage/ mother’s journey to camps. By this the viewer becomes a participant in the ritual related to the artwork. Symbolic references of parrots are made to the passive and easily pacified, non effective middleclass which Weerasinghe emphasized had a ‘peasant psychology’ii. My view of his work written in 1997 still stands : “his tough aesthetics resurrect obscure images which acknowledges the violent legacy of our immediate past, and its aftermath without being evasive, and gives no consolation to the convenient amnesiac. His art constantly remind us that contrary to the “modernist” aloofness from (socio-political) life, art can deal with such monumental calamities, and that inconvenient and unpleasant truths can, and should be interrogated.”iii While the exhibition’s enormous socio-political and art historical relevance remains solid, it also has its issues open for critique too. Referring to his narrative within his paintings, his obvious choice of a ‘mother’ going in search for a ‘son’ reinstates the societies 2 genderizing of ‘sons’ as the ‘defenders’ of citizen’s rights and political will, and ‘mothers’ as the ‘grievers & bearers’ of its pain. The ‘fathers’ as grievers and ‘daughters’ who were tortured and disappeared somehow does not find adequate acknowledgement in Weerasinghe’s work at aesthetic or conceptual level. His next major art project that had strong socio-political relevance was the ‘Shrine of the Innocents’, a monument build on Sri Jayawardena Pura in close proximity to the Sri Lanka’s Parliament, for 38 school children from Ambilipitiya disappeared while in Army custody during the youth uprising in the 1988- 1991 that turned the South of Sri Lanka into a killing field. Although it is highly politicized and politically motivated assignmentiv which is different to Weerasinghe’s other artistic endeavors, the Shrine of the Innocents’ was probably the most elaborate expression of Weerasinghe’s own attempts of dealing with his grief of seeing extensive violations inflicted on the youth, and guilt of being part of a society that watched in silence. It is also may be the closest he comes to most explicitly positioning the duality of his role: One that aligns his own pain with that of the victims of political violence and the other being part of the society which the perpetrators were produced. The entire design of the monument and all its elements points to the profound bearings of pain, betrayal, guilt, search of redemption and justice, solace and the cathartic need to share the grief of lost lives and loss of innocence: “The tablets with the thoughts of parents represent the narratives of violence in the recent past. At the opposite end, the flower altar as well as the coloring of the entire inner chamber is symbolic of the religious domain, where many people looked for solace when secular systems of justice and law and order failed. The clay objects on the white pedestals representing human heads are indicative of violent deaths. In other words, this ordering enmeshes violent death in between the religious domain and the narratives of violence...while simultaneously creating a somber and meditative atmosphere which creates the kind of environment in which to remember those who were lost and to ponder about the wider consequences of that period of political violence “ - (Perera 2007). For Weerasinghe, for that moment of catharsis, the connectivity with the parents of the victims disappeared and sharing in their collective grief was paramount in the whole process of building the monument: “ In the process of hand-molding the clay objects strewn on the floor of the central chamber referred above, the parents as a collective did get a chance for a process that can be called ‘public mourning”- (Perera 2007). While acknowledging the artists attempt to bring in a sense a relief and recognition of pain and loss experienced by the victims’ families and letting the amnesiac society not to forget the ‘horrors of their pathology’, the monument was critiqued for its dislocation from the geographical location of pain (the Ambilipitiya), and therefore distancing it from its immediate environment of memories and memorializing community which in many ways assured its ‘nonremembrance’ in the long run. Because of its highly politicized engagement with the power regime at the time, it also opened to the critic of exploitation of personal pain of victims’ families for political millage while it also allowed a public closure in the conscience of the political regimes so that they could conveniently forget about the larger violations of human rights and atrocities. Weerasinghe’s engagement with art became self absorptive in the following few years since his exhibition ‘Private Stuff’ in 1998 held at the Heritage Gallery. Not totally moving away from socio-political inquiry within his art Weerasinghe engages with his own sexual anxieties, uncertainties and his own masculine identity. His works ‘Portrait of an artist as a divine being’, (2001-2002), Confused narrative: that's the way life is, (2003) and (My) inability of painting woman (2000) brings into discussion politics and issues of (his) masculinity. His work brings us 3 close to the discussions on sexuality and its workings where gender identities get formed. Reading his art done during this period it is useful to understand the ideas of ‘homophobia’ that is discussed within gender studies and psychoanalysis. Linked to the unresolved sexual desires of the male child in the great oedipal processv in the Freudian model, the homoerotic desire is seen as a feminine desire for other men where homophobia is seen as an attempt to suppress it. Homophobia is defined as the male fear of not measuring up to other men in their masculine selves and therefore masculinity is a homosocial enactment where men constantly try to prove to the other men of their masculinityvi. Even if we do not refer to the Freudian psychoanalysis, as David Leverenze argues “ideologies of manhood have functioned primarily in relation to the gaze of male peers and male authority”vii. In his work mentioned above Weerasinghe deconstructs the myth of masculinity by positioning himself as the object of attention and revealing on the one hand its homoerotism by his obsessive tracings of hard penised explicit male profiles. On the other hand, by this very act of exploring the homoeroticism he undermine the typical homosocial behavior and procedure of the male in order to re-emphasize his masculinity. In other words, he presents a compromised masculinity that explores homoerotics in it as opposed to suppressing it and thereby highlighting its contradictions. The series of works titled (My) inability of painting woman and Your hair my eye 2003 shows Weerasinghe’s attempts at resolving the issues or rather his predicament in relation to women and femininity. The female figures with unyielding and unruly hair (symbolism directed towards the liberated/ independent woman), drawn imprisoned within the arrangement of pieces of fabric conventionally worn by home-making women. Juxtaposed this aesthetic content with the title (My) inability of painting woman indicates the duality of his perception of woman. It also indicates the dilemma and anxieties of the contemporary masculine man who is posited between idealized roles of the conventional woman and ideologically liberalized male perceptions of the ‘modern’ woman. Both (My) inability of painting woman and Your hair my eye deals with the male anxieties in relation to perceiving and understanding women in their assigned roles that fluctuates within traditional , modern and contemporary gender boundaries. However, both these exhibitions can be critiqued for not critiquing the typical male construct of ‘women as a mystery’ or successfully rejecting the conventional profiling of women, but rather falling into the same trap one way or other by merely replacing it with ‘male inability to understand’ (women). In his later ideas investigating the homoeroticism he links the notions of homophobia to the pathologic violence manifested in the society in multitude of ways (gender biases and suppression, ethno chauvinism, racism, religious fundamentalism, sexism, machoism) where he sees it as attempts of re-emphasizing the masculine power of the phallus. In Weerasinghe’s art, the act of suppressing homoeroticism, the ‘feminine’ within the male, is equated with the suppression of the ‘other’ who is perceived as a threat for their domination. His later series of works ‘Celestial Underwear, Dance of Shiva, Celestial Violence, Mics and Snakes chronologically develops the idea of political power as masculine power which resides within the state as well as religious bodies, political lobby groups, media institutions among others that support hegemonic discourses. This homosocial act of re-emphasizing the masculinity manifests as this immensely destructive oppressive macho power. It is within this diagram Weerasinghe explores ‘power and domination’ that manifests in the Sri Lankan socio-political landscape in his current works ‘celestial violence’ and ‘celestial fervor’. He looks at the combined effort of the institutionalized Buddhist’s and the extreme Sinhala nationalists’ larger plan for dominance which is articulated throughout Sri Lanka’s recent history to the masses through mass media where violence, destruction and desecration of humanity is justified, glorified and hero-fied as 4 ‘just acts’ that are necessary for the good of the country. It is worth mentioning here that homophobia is known to be closely linked to racism and sexism, and works on fear and intimidation. Commenting on Weerasinghe’s work ‘Man with knife’, a reading can be done on the use of ‘knife’. The knife, an object of everyday life in the kitchen that can turned into a handy weapon of violence forces us to rethink of the lethality of everyday taken for granted aspects of society when politically mobilized. Such are the public engagements of religions (in this case ‘politicized Buddhism’) and ‘instruments of mass media’ (symbolized by microphones and light boxes in Weerasinghe’s work) that helps to publicize the politicized rhetoric which claims superiority and justifications for domination within their religious articulations. Weerasinghe uses the color ‘saffron/ yellow’ as references for virulent forms of political Buddhism which he continues from his earlier work ‘Amnesiaic wall and yellow axes’, an installation done in 2004 on the same theme of problematic manifestations of Sinhala Buddhist nationalism. Ismail’s reading on ‘Man with knife’ (a work included in Celestial Fervor) he writes: “The brilliance of Man with knife lies in it bringing together, associating, everyday violence, mass communication and (Sinhala) masculinity, not simply with Sri Lankan Buddhist nationalism, but one of its holiest, carnivalesque, symbols, Wesak; with Wesak’s most public, iconic metonym, the pandal. To Buddhism, Gautama was born, attained nirvana and died on that poya. Buddhist Sri Lankans, of course, commemorate that day with, among other things, pandals. By mimicking them, this text asks its reader, at one level, to consider the relation between what might appear to be innocent, celebratory, apolitical Buddhism and politics, ideology. For the pandal, depicting scenes from Jataka stories, episodes in the life of Gautama, “communicates” with the masses, interpellates subjects: publicly, literally on the street. In so doing, it could be compared with the microphone at a political rally; though it works, primarily, on the unconscious”… Weerasinghe could have painted these images on canvas and made an effective, if straightforward, political statement about, intervention within, our present. By mimicking the form of the pandal, he connects this work with the iconic art form of Wesak, protests the politicization of Buddhism in Sri Lanka, its violent treatment of the other, through both form and content.viii Majority of the works included in Celestial Fervor uses these light box installations reminiscent of kitsch light box advertisements (particularly in the gambling places with the illuminated horse galloping to the flicker of the lights) as much as it reminds one of the illuminated religious contraptions in Buddhist festivals from Pandals to lanterns (as Ismail points out). Instead of the flickering horse, one could find flickering figures of soldiers with guns and Ligers (a combined features of lion and tiger) bearing their teeth alongside knifes moving inside the light boxes creating a beautiful, disco lighted atmosphere in the works titled Kitchen Knife & Ligers and Solders in Clouds. In addition to these, a bisected barrel is made transparent and suspended above ground. Similarly a transparent balustrade aptly titled Soaring Balustrade is hung above ground and illuminated to heighten the allure. Elements within these works have a sense of de-contextualization and are conspicuously festive and celebratory. Its allure acts as a veneer to cover the underlying potentialities of violence professed through politics, religion and mass culture. In this exhibition ‘Celestial Fervor’, the artist continuously nudges us to critically review our own anesthetized, duped perceptions and unhesitant consumptions of ‘ideology’ and ‘action’ that are shrouded in overused rhetoric of concepts such as ‘nationalism, patriotism, authenticity, cultural purity and religiosity’. Weerasinghe continues his trope of using elements from popular culture, art and archeology combining with his socio-politically heavy conceptualizations in ‘Celestial Fervor’ too, which makes the artwork layered and provides a broader canvas for viewers to connect and ponder in depth. His imagery although sometimes seems direct, they are imbued with irony, mimicry, 5 metaphors and interpretations that problematizes the most seemingly innocent, taken for granted aspects of life, society and ideology. Use of light boxes, illuminations, cut out male figures and using of knifes and wax are all done consciously to make meaning not only in the way they are used but also in the choice of using such material itself. This way, his art again intervenes critically not only in the socio-political ideology but also in the art historical discourse. i Jagath Weerasinghe, Sunday Observer, November 22 ,1992. ii Jagath Weerasinghe, 1997. Here his use of ‘peasant psychology’ refers not to people engaging in agriculture but to the ‘middle class intelligentsia, the professionals and the politician who enjoys the privileges of democracy and protections of its laws. iii Anoli Perera ,1997. iv The ‘Shrine for the Innocents’ was sponsored by the President Chandrika Kumaratunge’s government , The coordination of monument was done by its highly politicized program ‘ Sudu Nelum Movement, State Engineering corporation and Urban Development Authority. v First seeing through the eyes of the mother desiring the father, then identifying with father leaving the first desire for the masculine figure unresolved. vi Michael S. Kimmel,1994, pp. 128-133. vii D. Leverenze, 1991. viii Qadri Ismail, 2009. Bibliography Ismail, Qadri , 2009, Reading the Art of Jagath Weerasinghe, exhibition catalog of ‘Celestial Fantasy’. Pita Kotte: Theertha Red Dot Gallery. Kimmel, Michael S. (1994), Masculinity as Homophobia: Fear, Shame, and Silence in the Construction of Gender Identity, In, Theorizing Masculinities, ed. Harry Brod and Michael kaufman, Thosand Oaks : Sage. Leverenze. D, (1991), The Last Real Man in America: From Natty Bumppo to Batman, American Literary Review, 3. th Perera, Anoli, (1997), A Socio-Political Reading of Yantra Gala, Sunday Observer, 5 October 1997, Colombo: Lake House. Perera, Sasanka, (1997), Public Space and Monuments: Politics of Sanctioned and Contested Memory, South Asia Journal for Culture, Vol. I, Pitakotte: Colombo Institute/Theertha. Weerasinghe, Jagath, (1997), Yantra Gala and Round Pilgrimage, concept note of the exhibition (in Sinhala), Colombo: Heritage Gallery. 6