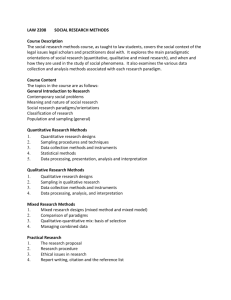

Research Design in Qualitative/Quantitative/Mixed Methods

advertisement