A Skeptical View of

Repressed Memory Evidence

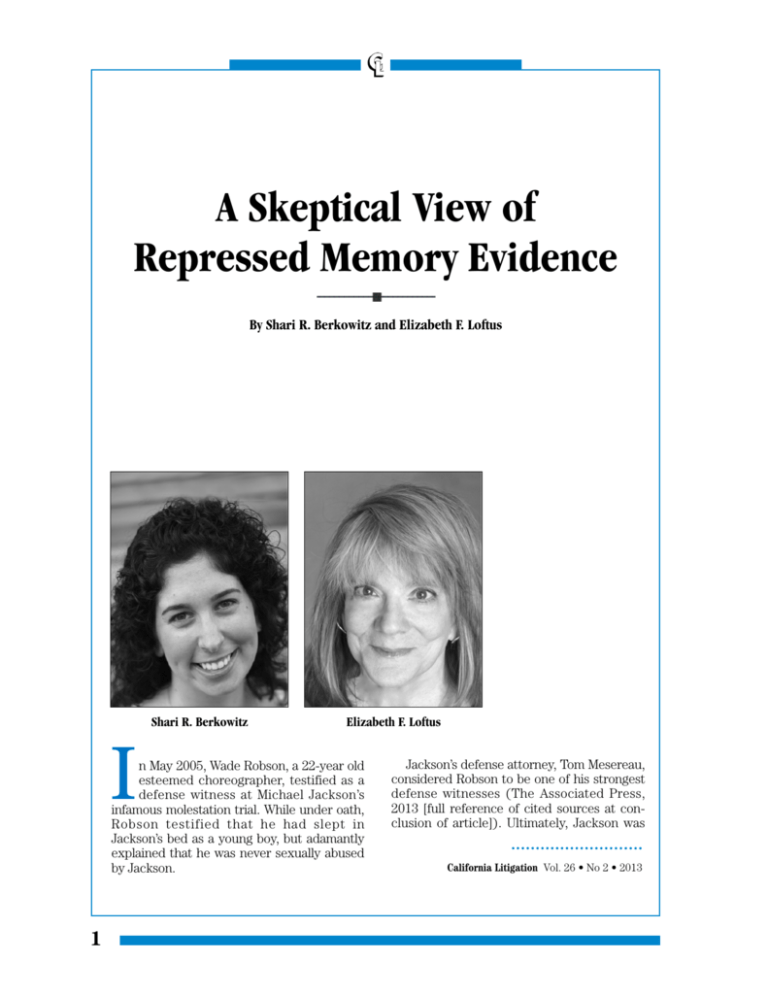

By Shari R. Berkowitz and Elizabeth F. Loftus

I

Shari R. Berkowitz

Elizabeth F. Loftus

n May 2005, Wade Robson, a 22-year old

esteemed choreographer, testified as a

defense witness at Michael Jackson’s

infamous molestation trial. While under oath,

Robson testified that he had slept in

Jackson’s bed as a young boy, but adamantly

explained that he was never sexually abused

by Jackson.

1

Jackson’s defense attorney, Tom Mesereau,

considered Robson to be one of his strongest

defense witnesses (The Associated Press,

2013 [full reference of cited sources at conclusion of article]). Ultimately, Jackson was

California Litigation Vol. 26 • No 2 • 2013

acquitted of all charges. In 2009, Jackson

passed away, and two months after his

death, Robson was quoted as describing

Jackson as a “kind human being” (CNN,

2013).

Yet, on May 1, 2013, Robson sought permission from the Los Angeles probate court

to file a claim against Michael Jackson’s

‘

…decades of scientific

research have shown that

people can develop false

(New York Daily News, 2013).

Although the facts of Robson’s claim will

surely attract a great deal of media attention,

this will not be the first time that a California

court has been asked to consider a repressed

memory claim. In one of the most famous

cases, more than two decades ago in 1990,

Eileen Franklin-Lipsker testified in the San

Mateo County Courthouse that she had witnessed her father, George Franklin, murder

her best friend, Susan Nason in 1969. Eileen

explained that she had repressed her childhood memories of Susan’s murder for 20

years. With nothing more than Eileen’s recovered (de-repressed) memories, Franklin was

found guilty of murder.

Around this same time, in another famous

case, Holly Ramona, accused her father, Gary

Ramona, of years of brutal child sexual abuse.

Like Eileen, Holly, claimed that she had

repressed her traumatic childhood memories.

memories of events that have

— A Dearth of —

Credible Scientific Evidence

never actually happened to

Over the last three decades, California

courts (as well as courts in other states and

throughout the world) have been forced to

consider claims of repressed memories. Yet

despite the popularity of these claims, it

might surprise readers to learn that there is

virtually no credible scientific support for the

notion of repression. In other words, there is

no evidence to suggest that highly traumatic

childhood memories can be unwittingly banished from the conscious mind and stored in

the unconscious mind in pristine condition

for many years, only to be recalled later.

Harvard Psychology Professor, Richard

McNally, made this same point succinctly

when he wrote: “The notion that the mind

protects itself by repressing or dissociating

memories of trauma, rendering them inaccessible to awareness, is a piece of psychiatric

folklore devoid of convincing empirical support” (McNally, 2003, p. 275).

Yet the debate over the existence of repressed memories remains one of the most

controversial topics in the field of psychology

’

them before…

estate. Robson now claims that Jackson sexually abused him over a seven-year period,

starting when he was seven years old.

Why would Robson, who previously testified under oath that he had never been

molested, suddenly claim years of abuse at

the hands of Jackson? Robson’s lawyer,

Henry Gradstein, explained that Robson had

recently suffered an emotional breakdown

(The Associated Press). Media sources

reported that Robson subsequently received

weeks of psychotherapy (TMZ, 2013), and

according to Gradstein, Robson recovered

his repressed memories of child sexual abuse

2

(Lindsay & Read, 2001). Commonly referred

to as the “memory wars,” psychologists have

long debated the nature of traumatic memory. Even today, it is not unusual for scientific

conferences and scientific journal articles to

focus on the recovered memory debate, as

the phenomenon of repressed memory is still

highly controversial. For instance, in 2010,

respected University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Professor Robert Belli organized a symposium on the recovered memory debate. As

Belli (2012) stated in his subsequent article,

‘

Specifically, we

believe that it

may be premature

for repressed

memory evidence

to be accepted

’

in the courts…

“In seeking the latest thinking and evidence

pertaining to the recovered memory debate,

the aim of the symposium was to provide a

forum for contrasting views that would provide a comprehensive picture of the differing

perspectives that characterize the current

state of affairs” (p. 9).

3

— Contrasting Theories —

As for these contrasting views, McNally

(2003) explains that on one side, psychological scientists and some clinicians reject the

notion that memories can be repressed and

highlight that history reveals that incredibly

traumatic memories (e.g., Holocaust survivors’ memories of the concentration

camps) are not forgotten. On the other side,

some psychiatrists and some clinicians insist

that traumatic memories are immune from

the traditional malleable nature of human

memory, and that highly traumatic childhood

memories can be repressed in the unconscious mind for many years.

In support of this pro-repression view,

some advocates rely on clinical experience,

anecdotal case histories, and also flawed

research studies (for more on the limitations

of these case histories, see Loftus & Guyer,

2002). For example, repressed-memory enthusiasts often cite to a study by L.M. Williams (1994) as the single best example that

massive repression of child sexual abuse is a

common phenomenon.

In the early 1970s, Williams collected the

hospital records of 206 female children who

reported that they had been sexually abused.

Approximately 17 years later, Williams located and contacted these same female children

(who were now adult women), and interviewed 129 of them about their prior experiences in the hospital, their psychological

health, and their prior histories of child sexual abuse. Williams found that 38% of the adult

women did not disclose the original child sexual abuse incident that led to their hospital

visit. This result prompted Williams (1994) to

conclude that “…having no recall of child

sexual abuse is a common occurrence for

adult women with documented histories of

such abuse” (p. 1174).

Williams’ conclusion, however, should be

interpreted with great caution. In particular,

as Loftus, Garry, and Feldman (1994) explain, it is not surprising that some of the

women failed to disclose the original child

sexual abuse incident that led to their hospital visit in the first place.

Failure to disclose abuse is not synonymous with repression. For example, it is possible that some of the women in Williams’

study were too embarrassed or ashamed to

disclose their abuse. Likewise, consider that

some of the women in Williams’ study were

simply too young when the abuse originally

happened to have memories of it in the first

place (for more on childhood amnesia, see

Hayne, 2004).

Additionally, given that forgetting is a normal process of human memory, it is possible

that some of the women may have naturally

forgotten about the abuse. Moreover, the

majority of women who did not disclose the

original child sexual abuse incident told of

other child sexual abuse events. Furthermore, a more recent study by Goodman et al.

(2003) of memory for child sexual abuse

revealed that only 8% of adults failed to disclose their original child sexual abuse histories. For these reasons and more, we cannot

conclude from Williams’ study that repression

is the driving force behind why 38% of

women failed to disclose of their child sexual

abuse histories.

Why People Might

— Sometimes Think —

They Repressed Memories

Therefore, the question undoubtedly arises: If there is no credible scientific support for

repression, why do people sometimes believe

that they have recovered previously repressed memories of child sexual abuse?

McNally and Geraerts (2009) posit that there

are other non-repression explanations that

may explain why an adult may later claim to

have recovered a memory of child sexual

abuse. Specifically, it is possible that a child

was too young at the time of the abuse to

have interpreted the event as traumatic child

sexual abuse (Clancy, 2009). Thus, the new

traumatic interpretation of the event as abuse

may lead an adult to now state that she is the

victim of child sexual abuse, but this “new

memory” is not explained by repression.

Also, it is possible that an adult may claim

that she repressed her memories of child sexual abuse, but she may have forgotten that

she had actually remembered the abuse in

the past (see Schooler, Ambadar, & Bendiksen, 1997 for more on the forgot-it-allalong effect). Likewise, it is possible that a

person may intentionally try not to think

about the child sexual abuse (McNally &

Geraerts). If this is the case, it is important to

remember that deliberate avoidance is not

the same as unconscious repression.

While these explanations may help us

understand some recovered memory cases,

where did Wade Robson’s memories of child

sexual abuse, Eileen Franklin-Lipsker’s memories of murder, and Holly Ramona’s memories of brutal child sexual abuse come from?

These cases, as well as many others, illustrate

that recovered memories of child sexual

abuse may sometimes be a product of suggestion (Loftus & Ketcham, 1994). Whether

the suggestion(s) comes from a therapist or

another source (e.g., media), real-life cases

and research studies demonstrate that many

suggestive techniques can lead people to create false memories.

In fact, decades of scientific research have

shown that people can develop false memories of events that have never actually happened to them before (for a review, see

Loftus, 2003). Specifically, researchers have

led a substantial minority of subjects to falsely believe and/or remember that as children

they had: nearly drowned as a child and had

to be rescued by a lifeguard (Heaps & Nash,

2001), witnessed their parents having a physically violent fight (Laney & Loftus, 2008),

had their ear inappropriately licked by the

Pluto character at Disneyland (Berkowitz,

Laney, Morris, Garry, & Loftus, 2008), and

witnessed their friend’s demonic possession

(Mazzoni, Loftus, & Kirsch, 2001).

It is worth emphasizing that the tech-

4

niques that have led people in psychology

experiments to develop false memories of

these mildly traumatic and bizarre events are

similar to the techniques that are often used

by recovered memory therapists. Some of

these suggestive techniques include: interpreting a person’s dreams to indicate that

they have been abused, placing a person into

group therapy where they are exposed to

others’ stories of child sexual abuse, utilizing

hypnosis or sodium amytal treatment, reliving a person’s past through guided imagery,

and giving a person false feedback that their

symptoms suggest they were likely sexually

abused. Moreover, the use of these techniques may lead a person to develop false

memories of child sexual abuse.

One only needs to look a little further into

Eileen Franklin-Lipsker’s case or Holly

Ramona’s case to see that their recovered

memories of murder and sexual abuse were

likely a product of these suggestive therapeutic methods (Johnston, 1997). Ultimately, the

accused in these cases eventually regained

their liberty and reputation — George Franklin was released from prison in 1996 after it

was learned that Eileen’s recovered memories were a product of hypnosis and Gary

Ramona successfully sued Holly’s therapists

for planting false memories in the mind of his

daughter. Nonetheless, the toll these cases

can have is far too great for us to ignore.

— How Courts —

Should Approach It

While the number of repressed memory

cases in the legal system may be declining

since the heyday of the “memory wars,”

Wade Robson’s case reminds us that

repressed memory allegations are not yet a

thing of the past. Therefore, it is important

that lawyers and judges be familiar with the

repressed memory controversy.

Specifically, we believe that it may be premature for repressed memory evidence to be

accepted in the courts, and we believe that

people should not be forced to defend accusations based on such a scientifically unsup-

5

ported claim. Furthermore, under the Frye

standard, the huge controversy over this

topic is proof enough that the claim that

highly traumatic childhood memories can be

repressed has not gained general acceptance

in the scientific community.

If a court does decide to admit such evidence into trial, we would encourage judges

to consider cautionary jury instructions that

explain to jurors that there is no credible scientific support for repression and that there

are many suggestive techniques that can lead

people to create false memories. Alternative

explanations for a claimant’s repressed memory allegations should also be actively contemplated.

Furthermore, since individuals who have

been involved in psychotherapy frequently

make these accusations, access to therapy

records is often crucial for revealing the

kinds of suggestion that repressed memory

claimants have been exposed to. In our experience, an examination of therapy notes and

records, and deposition testimony from therapists, has revealed examples of suggestion

that may have led to mistaken recollections

and false accusations. Such information is

frequently accessible in civil cases, but not in

criminal ones, and yet the information is just

as crucial in both (see Loftus, Paddock, &

Guernsey, 2006 for more discussion of this

issue).

In the end, while it remains to be seen

what the court will decide with Wade Robson’s claim, what we do know is that there is

no credible scientific support for the notion

of repression, and thus it might be time for

repressed memory claims to, as Michael

Jackson himself once sang, “just beat it.”

— References —

Belli, R. F. (Ed.). (2012). True and false recovered memories: Toward a reconciliation of the

debate. Vol. 58: Nebraska Symposium on

Motivation. New York: Springer.

Berkowitz, S. R., Laney, C., Morris, E. K.,

Garry, M., & Loftus, E. F. (2008). Pluto behaving

badly: False beliefs and their consequences.

American Journal of Psychology, 121, 645-662.

Clancy, S. A. (2009). The trauma myth: The

truth about the sexual abuse of children — and

its aftermath. New York: Basic Books.

CNN. (2013). Michael Jackson defender files

sex abuse claim. Retrieved May 16, 2013, from

http://www.cnn.com.

Hayne, H. (2004). Infant memory development:

Implications for childhood amnesia. Developmental Review, 24, 33-73.

Heaps, C. M., & Nash, M. (2001). Comparing

recollective experience in true and false autobiographical memories. Journal of Experimental

Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition,

27, 920-930.

Goodman, G. S., Ghetti, S., Quas, J. A., Edelstein, R. S., Alexander, K. W., Redlich, A.

D.,…Jones, D. P. H. (2003). A prospective study

of memory for child sexual abuse: New findings

relevant to the repressed-memory controversy.

Psychological Science, 14, 113-118.

Johnston, M. (1997). Spectral evidence: The

Ramona case: Incest, memory, and truth on

trial in Napa Valley. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Laney, C., & Loftus, E. F. (2008). Emotional

content of true and false memories. Memory, 16,

500-516.

Lindsay, D. S., & Read, J. D. (2001). The recovered memories controversy: Where do we go from

here? In G. Davies & T. Dalgleish (Eds.),

Recovered memories: Seeking the middle

ground (pp. 71-94). New York: Wiley.

Loftus, E. F. (2003). Make-believe memories.

American Psychologist, 58, 864-873.

Loftus, E.F. & Ketcham, K. (1994). The myth

of repressed memory: False memories and allegations of sexual abuse. NY: St. Martin’s Press.

Loftus, E. F., Garry, M., & Feldman, J. (1994).

Forgetting sexual trauma: What does it mean

when 38% forget? Journal of Consulting and

Clinical Psychology, 62, 1177-1181.

Loftus, E. F., & Guyer, M. J. (2002) Who

abused Jane Doe? The hazards of the single case

study: Part 1. Skeptical Inquirer, 26, 24-32.

Loftus, E. F., Paddock, J. R., & Guernsey, T. F.

(1996). Patient-psychotherapist privilege: Access

to clinical records in the tangled web of repressed

memory litigation. University of Richmond Law

Review, 30, 109-154.

Mazzoni, G. A. L., Loftus, E. F., & Kirsch, I.

(2001). Changing beliefs about implausible autobiographical events: A little plausibility goes a

long way. Journal of Experimental Psychology:

Applied, 7, 51-59.

McNally, R. J. (2003). Remembering trauma.

Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard

University Press.

McNally, R. J., & Geraerts, E. (2009). A new

solution to the recovered memory debate. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4, 126-134.

New York Daily News. (2013). Choreographer

Wade Robson’s breakdown from ‘stress and

sexual trauma’ triggered memories of Michael

Jackson molestation, says lawyer. Retrieved

May 16, 2013, www.nydailynews.com.

Schooler, J. W., Ambadar, Z., & Bendiksen, M.

(1997). A cognitive corroborative case study

approach for investigating discovered memories

of sexual abuse. In J. D. Read and D. S. Lindsay

(Eds.), Recollections of trauma: Scientific evidence and clinical practice (pp. 379-387). New

York and London: Plenum Press.

The Associated Press. (2013). Former

Jackson defender now says singer abused

him. Retrieved May 16, 2013, from www.bigstory.

ap.org.

TMZ. (2013). Wade Robson — Nervous

breakdown triggered Michael Jackson

molestation memories. Retrieved May 16, 2013,

from www.tmz.com.

Williams, L. M. (1994). Recall of childhood

trauma: A prospective study of women’s memories of child sexual abuse. Journal of Consulting

and Clinical Psychology, 62, 1167-1176.

Shari R. Berkowitz is an Assistant Professor of

Forensic Psychology at Roosevelt University in

Chicago, Illinois. Elizabeth F. Loftus is a

Distinguished Professor at the University of

California, Irvine, and holds positions in the

Departments of Psychology and Social Behavior, Criminology, Law & Society, Cognitive

Sciences, as well as the Law School. Both Dr.

Berkowitz and Dr. Loftus have trained attorneys and judges on the malleability of human

memory, and have consulted on and testified

in cases involving memory distortion and

suggestibility.

6