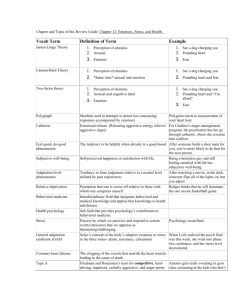

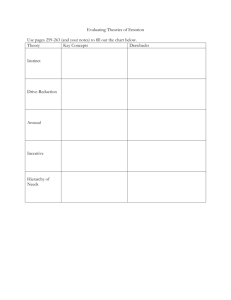

The Schachter Theory of Emotion: Two Decades Later

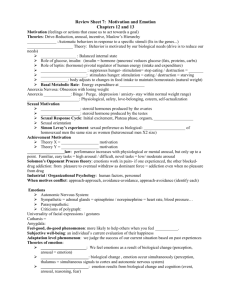

advertisement