Regulatory Controls in the Mass Media

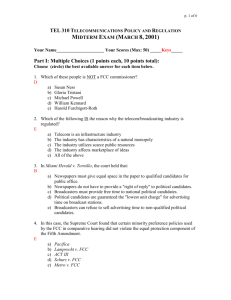

advertisement