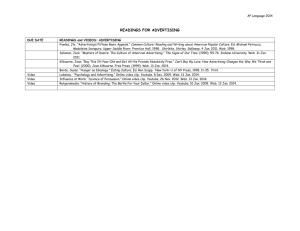

Distinguishing Commercial from Noncommercial Speech

advertisement