Hasvold - Rubin v

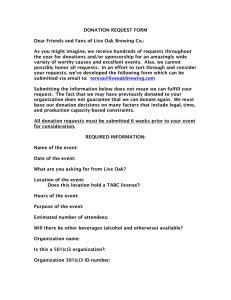

advertisement

Coors’ Real Silver Bullet: The First Amendment Matt Hasvold* While many consumers today take for granted that they can look at the alcohol content on a beer label, this wasn’t always so. Following the repeal of Prohibition, Congress found it necessary to strictly regulate the country’s newly-legal vice with the 1935 Federal Alcohol Administration Act (FAAA). Among the Act’s rules was a provision that prohibited the printing of alcohol content on beer labels.1 Brewers were limited by this rule for several decades until 1987, when Coors Brewing Company finally raised a challenge. Coors applied to the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms (ATF) for approval of proposed labels and advertisements that disclosed the alcohol content of its beer. When the ATF denied the application, Coors brought suit seeking injunctive relief and a declaratory judgment that the labeling ban violated the First Amendment’s free speech protections.2 Restrictions on non-misleading commercial speech are only constitutional when they advance a “substantial government interest” and are narrowly tailored to directly advance the asserted interest.3 The government in Rubin argued that it had a substantial interest in preventing “strength wars,” in which brewers would compete for sales based on the potency of their beer. While the Court agreed that this was a substantial government interest, it found the myriad of labeling requirements confusing and irrational. For instance, while beer manufacturers were * Matt Hasvold is a J.D. candidate at Creighton University School of Law. He holds a B.S. from South Dakota State University, where he studied economics and political science. His favorite beer is Lost Continent Double IPA by Grand Teton Brewing. 1 2 3 27 U.S.C. § 205(e)(2) (1988). See Rubin v. Coors Brewing Co., 514 U.S. 476, 478–79 (1995). Central Hudson Gas & Elec. Corp. v. Public Service Commission of N.Y., 447 U.S. 557, 566 (1980). 1 prohibited from including alcohol content on their labels, it was required for other sectors.4 Because the restrictions were convoluted and inconsistent, the Court found that the beer labeling restriction was not narrowly tailored to prevent strength wars. Overturning the provision, the Court stated that “the irrationality of this unique and puzzling regulatory framework ensures that the labeling ban will fail to achieve that end.”5 This decision lifted the federal government's ban on alcohol content labeling and returned the issue to state control. While states must construct their laws carefully to prevent impermissible free speech restrictions like those found in the FAAA, the Court held that “[s]tates clearly possess ample authority to ban the disclosure of alcohol content.”6 Where states choose to permit publication of alcohol content on beer labels but do not regulate the manner of statement, federal regulations were passed after Rubin to require that alcohol content be clearly indicated and measured in percent alcohol by volume.7 The most surprising aspect of the Rubin decision is not that the Court struck down a restriction on labeling the alcohol content of beer, but that it took six decades to do so. The rationale advanced by the government in support of the 1935 restriction was that mere publication of alcohol content on beer cans would change the basis on which consumers make their purchasing decisions, leading to more potent brews and a higher rate of alcoholism.8 But as the Rubin Court recognized, the chain of logic supporting this “substantial government interest” was inherently flawed. First, it assumed that a significant portion of beer drinkers base their decisions solely on 4 See 27 C.F.R. § 4.36 (1994) (requiring labeling of alcoholic content on wines) and § 5.37 (requiring labeling of alcoholic content on spirits). 5 Rubin, 514 U.S. at 489. 6 Rubin, 514 U.S. at 486. 7 27 CFR § 7.71 (2004). 8 See Rubin, 514 U.S. at 487. 2 alcohol content. As anyone who has been to college can attest, this group certainly exists—but their numbers are small, and few are actually alcoholics. Second, the government's argument presupposed that beer manufacturers would change their formula to appeal to this small group. However, simple economics dictates that companies can rarely succeed when they overhaul their product to appeal to a minority of consumers. Finally, the government assumed the only obstacle between these consumers and alcoholism is a blind-fold. If such people exist, I pray they never discover vodka. 3