Malleus Maleficarum

advertisement

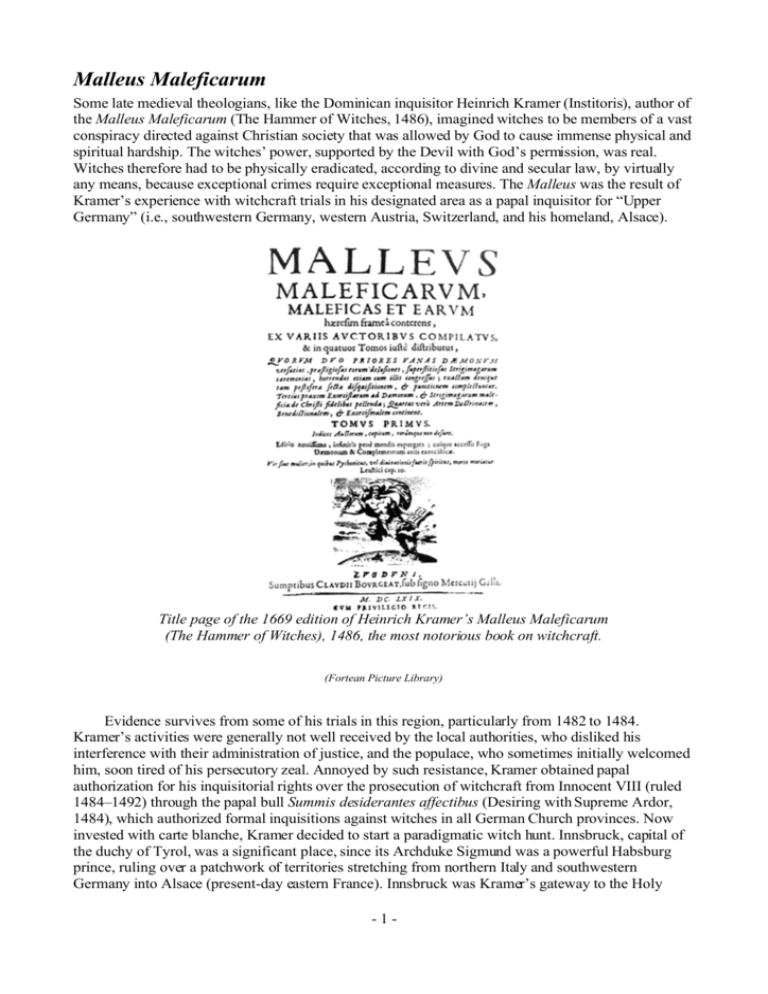

Malleus Maleficarum Some late medieval theologians, like the Dominican inquisitor Heinrich Kramer (Institoris), author of the Malleus Maleficarum (The Hammer of Witches, 1486), imagined witches to be members of a vast conspiracy directed against Christian society that was allowed by God to cause immense physical and spiritual hardship. The witches’ power, supported by the Devil with God’s permission, was real. Witches therefore had to be physically eradicated, according to divine and secular law, by virtually any means, because exceptional crimes require exceptional measures. The Malleus was the result of Kramer’s experience with witchcraft trials in his designated area as a papal inquisitor for “Upper Germany” (i.e., southwestern Germany, western Austria, Switzerland, and his homeland, Alsace). Title page of the 1669 edition of Heinrich Kramer’s Malleus Maleficarum (The Hammer of Witches), 1486, the most notorious book on witchcraft. (Fortean Picture Library) Evidence survives from some of his trials in this region, particularly from 1482 to 1484. Kramer’s activities were generally not well received by the local authorities, who disliked his interference with their administration of justice, and the populace, who sometimes initially welcomed him, soon tired of his persecutory zeal. Annoyed by such resistance, Kramer obtained papal authorization for his inquisitorial rights over the prosecution of witchcraft from Innocent VIII (ruled 1484–1492) through the papal bull Summis desiderantes affectibus (Desiring with Supreme Ardor, 1484), which authorized formal inquisitions against witches in all German Church provinces. Now invested with carte blanche, Kramer decided to start a paradigmatic witch hunt. Innsbruck, capital of the duchy of Tyrol, was a significant place, since its Archduke Sigmund was a powerful Habsburg prince, ruling over a patchwork of territories stretching from northern Italy and southwestern Germany into Alsace (present-day eastern France). Innsbruck was Kramer’s gateway to the Holy -1- Roman Empire. Kramer’s Inquisition in Innsbruck, starting in July 1485, employed intimidation, brutal force, and unlimited torture; denied legal defense; and issued distorted reports of his interrogations: scandalous conduct, even by late-fifteenth-century legal standards. Therefore, not only the relatives of the accused but also citizens of Innsbruck, together with the clergy, the Tyrolean nobility and eventually the local bishop, protested against his illegal procedures. Bishop Georg II Golser, successor of the philosopher Nicolaus of Cusa at the see of Brixen, appointed a commission to scrutinize Kramer’s Inquisition. Despite desperate resistance from the inquisitor’s side, the bishop stopped the persecution immediately, nullified its results and (after having secured the archduke’s support), liberated all suspected women. It is worth remembering that both the secular and ecclesiastical authorities of Tyrol decided to resist this papal inquisitor and that they successfully prevented a witch persecution within their jurisdiction. Kramer was branded a fanatic, and Bishop Golser (who called Kramer senile and crazy in his correspondence) even threatened him with force if he failed to leave his diocese voluntarily. The prince-bishops of Brixen never allowed a witch persecution in their territory, and, even more importantly, the Tyrolean government had learned a lasting lesson and subsequently suppressed any attempts by lower courts to launch witch hunts. In short, the Innsbruck Inquisition was a crushing defeat for the papal inquisitor. His failure at Innsbruck and his apocalyptic fears drove Kramer to develop his ideas further. Starting from his reports to Bishop Golser (Ammann 1911), he hastily systematized his notes into a lengthy manuscript. This papal inquisitor was among the first of his profession to recognize the importance of the printing revolution, and with this manuscript he tried to turn his defeat into victory by demonstrating the existence of witchcraft. Using his authority and experience, he urged the necessity of a campaign to eradicate witchcraft. The result was the Malleus Maleficarum. Much confusion persists about the author, place of print, and date of print of this crucial publication on witchcraft. Even recently, scholars have claimed that the Malleus was at least coauthored by Jacob Sprenger (1437–1495). Only in 1519, decades after Sprenger’s death, was he named as author on a front page, first in an edition by the Nuremberg (Nürnberg) printer Friedrich Peypus. Two generations later, in 1574, Giovanni Antonio Bertanus, a Venetian printer, even named Sprenger as its sole author. Later German and French printers adopted Bertanus’s mistake. However, no contemporary evidence suggests that Sprenger had anything to do with the Malleus, or with witchcraft trials, or with executions of any kind as a result of inquisition trials. The author of the Malleus stated that forty-eight women had been burned as witches in the diocese of Constance; there is no reason to doubt this number, especially because he indicated that he himself had searched this diocese more than any other. All these remarks pointed directly to “frater Henricus de Sletstat,” or “Heinrich Institoris,” as Kramer often Latinized himself. The historian Sönke Lorenz found a hitherto unknown letter of this inquisitor from 1484, announcing his arrival at Wolfegg, a Swabian castle of Count Johann von Waldburg-Trauchburg (ruled 1460–1505)—close relatives to the ruling prince-bishop of Constance—for the purpose of witch hunting. Numerous documents survive concerning Kramer’s inquisition in the Imperial City of Ravensburg, mentioned in the first (Speyer 1486) edition of the Malleus (fol. 44r). After his crushing failure at Innsbruck, Kramer turned his attention toward Alsace, particularly in the vicinity of his convent. The expulsion of the Jews from his hometown of Séléstat should be placed in this context. In 1488 Kramer tried to incite witch hunts in the neighboring diocese of Trier; that year, thirty-five witches were burned in the nearby imperial city of Metz. In an expert opinion for the imperial city of Nuremberg, “Bruder Heinrich Kramer Prediger Ordens” boasted in October 1491 that “more than 200 witches” had been burned thus far due to his inquisitions, and in the same document he revealed his single authorship of the Malleus (Jerouschek 1991). Further actions of this inquisitor remain shrouded in darkness, and recent research suggests that his own superior may have silenced him. Jacob Sprenger turned out to have been Kramer’s most bitter -2- enemy. In complete contrast to the Alsatian fanatic, a maverick who managed to get into trouble wherever he went and who had developed into a wandering inquisitor and persecution specialist, Sprenger was a prominent figure among the “observant” reform wing of the Dominicans. He was appointed prior of the large Cologne convent, then leader of the “Teutonic” province; Sprenger was also an influential theologian, promoting veneration of the Virgin Mary and introducing rosary brotherhoods organized by friars and secular clergy for lay people. It seems likely that Sprenger was involuntarily included in both the papal bull of 1484 and the foreword of the Malleus in 1486. Wilson (1990, 130) doubted that Kramer tried deliberately to deceive the public and Sprenger, but this must have been the case. Sprenger had tried to suppress Kramer’s activities in every possible way. He forbade the convents of his province to host him, he forbade Kramer to preach, and even tried to interfere directly in the affairs of Kramer’s Séléstat convent. Not one single fact or incident associated Sprenger with witchcraft prosecutions, and he apparently managed to drive the author of the Malleus from his province. Kramer spent his final years in Italy and Moravia, where he died. Kramer successfully deceived many modern scholars with his misrepresentations and outright lies. But one need only read the surviving Innsbruck trial records (Ammann 1890) and compare them with his accounts of the Innsbruck inquisition in the Malleus to realize that Kramer was ready to use any deception that served his purpose. His career offers numerous examples, but this one seems sufficient (Segl 1988). As to date and place of print, a printer’s account book (Geldner 1964) demonstrated that the Malleus was first printed in autumn 1486 in the imperial city of Speyer, by then a medium-size town on the Rhine with about 8,000 inhabitants. The printer was Peter Drach (ca. 1450–1504), who delivered the “treatise against sorcerers” to booksellers by December 1486. The original text of the Malleus comprised 129 leaves (258 pages) in folio; given the usual production of a small printer (about 900 folio pages a day), Drach could have printed 150 copies a month. If the first edition was meant to have 300 copies, the manuscript must have been delivered to Drach by mid-October 1486, with more copies even earlier. Like many early books, it had no title page at that stage, so descriptions of the Malleus vary in the account book. The Malleus was called a “treatise against sorceresses,” or “against sorcery,” until Kramer added a foreword to the text, his apologia auctoris in malleum maleficarum, around Easter 1487 (Behringer and Jerouschek in Kramer 2000, 22–31). Afterward, the book’s title was fixed and appears regularly this way in the account book, even without the Malleus having a title page. Kramer promoted his publication in every possible way, notably by adding the papal bull of 1484 and a reference to its approval by the University of Cologne from April 1487. The latter was at least partly a forgery, because two of its supposed authors (Thomas de Scotia and Johann von Wörde) later denied any participation. These additions were not printed by Drach but by an immediate apprentice of Johannes Gutenberg at Mainz, Peter Schöffer (ca. 1425–1503), with a separate pagination. These parts were probably added in late May 1487 and bound together with the existing main body of the text. Henceforth, the author’s Apologia, the papal bull Summis desiderantes affectibus, and the Cologne Approbatio remained part of the Malleus. In early December 1486, when Speyer hosted a meeting of representatives of the imperial cities (Städtetag), and Emperor Frederick III (whom Kramer had insulted some years earlier, to the great displeasure of the Dominican order) was due to arrive, Kramer apparently traveled to the Burgundian capital at Brussels in order to obtain a privilege from King Maximilian I (1459–1519), the future emperor. The response must have been so unfavorable that it was not inserted into the foreword, although it was mentioned there, thus conveying the impression that the highest ecclesiastical, academic, and secular authorities backed the Malleus. Kramer’s strategy was aimed at the princes and their law courts. However, educated theologians and lawyers must have noticed that authoritative authors, like St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas, as well as Roman law, were deliberately twisted and misquoted in the Malleus. Moreover, Kramer brazenly emphasized the success of his inquisition at Innsbruck and even thanked the archduke for his support. He was correct in assuming that few would check his claims. -3- By reconstructing Kramer’s itinerary, it becomes clear that the Malleus was assembled hastily, within nine months. Starting with his opinions and apologies to the bishop of Brixen and the archduke of Tyrol, Kramer, after his expulsion from Innsbruck in February 1486, mined some standard textbooks of scholastic theology (Thomas Aquinas, Antonius of Florence), a few inquisitors’ manuals (Nicolas Eymeric), and earlier sermon notes. These indispensable texts were only available in the libraries of larger Dominican monasteries like Salzburg, Augsburg (Siemer 1936), Speyer, or his own convent at Séléstat. At one of these places, the Malleus must have been assembled. In the first edition (Speyer 1486, fol. 44r), Kramer told us that at least parts of it were written in the imperial city of Speyer, where he was physically present in autumn 1486, because Peter Drach had agreed to publish his text without delay. Kramer may have been unable to publish it at a more important printing center like Augsburg or Strasbourg. Kramer’s haste explains why the Malleus bristled with inconsistencies throughout. Contradictions and mistakes of all kinds (meaning, grammar, spelling) abounded; even the gender of the witches (malefica/maleficus) varied continuously, although the text was clearly directed against female witches. The most striking evidence for this haste comes from the Malleus itself. According to its contents, forty-eight questions were to be treated, but Kramer completely ignored this structure and ended with eighty-six chapters, unevenly distributed over three “parts,” two of them further subdivided. Part 1 supposedly contained sixteen chapters, but it actually had eighteen. The additional chapters, with new examples, were obviously added afterward; Chapter 17 claimed to be an extension of chapter 14, which had presumably been printed already. Part 2 supposedly contained sixteen chapters but ended up with twenty-five. Large chunks of its text were never mentioned in its table of contents; its headings hardly ever matched; whole chapters advertised in the contents were lacking; some were wrongly numbered; cross-references usually led nowhere. It was obviously a work in progress, its author continually adding more evidence until the last possible moment, but without proofreading. The practical difficulties of compiling such a massive text under extreme time pressure and premodern conditions can hardly be underestimated. We can only guess why the maverick inquisitor became a maverick author and wrote a desperate book under such desperate conditions. Perhaps he feared more important dangers from the approaching emperor or from Jacob Sprenger, whose name he was again about to misuse and whose election as provincial superior of the German Dominicans was imminent. The same day Sprenger became successor to Jacob Strubach as provincial superior (October 19, 1487), he obtained permission from his general, Joaquino Turriani, to lash out adversus m[agistrum] Henricum Institoris inquisitorem (against Master Heinrich Kramer, inquisitor). But perhaps the source of Kramer’s haste should be sought in the realm of the irrational; apocalypticism seemed a good guess, if we took the author’s Apologia seriously. If the end of the world was nigh, grammar became unimportant. Kramer’s main concern was witchcraft, or the heresy of witchcraft, but we must still explain his particular obsession with female witches. One likely explanation is the legacy of Christian theology, with its long-standing assertion of increased female susceptibility to temptations of the Devil, starting with Eve. This was certainly the starting point for the misogyny of the Malleus, whose author devoted several pages to explaining female inclinations to witchcraft, and recommended the subject for preaching, because women had a particular desire for instruction. His first demonstration of the malice of females was the Bible; he then cited instances of female credulity and their physical qualities, in particular the changeability of their complexion, leading to a vacillating nature. He then referred to their slippery tongues, which made them share their magic with friends, with whom they employed maleficium (harmful magic) because they were too weak to take revenge otherwise. Worst of all, however, because of their changeability, women were less inclined to believe in God. At this point, Kramer inserted a unique “realist” etymology of femina: “fe” is taken as an abbreviation of “fides” (belief); combined with the suffix “minus,” it literally translates into “she who believes less.” In the eyes of the Dominican inquisitor, a woman’s lack of belief was the basis for her apostasy and witchcraft (Speyer 1486, fol. 20–21). -4- Kramer’s paranoid emphasis on the dangers triggered by females contrasts strikingly with the attitude of his main opponent within the German Dominicans, the Cologne prior Jacob Sprenger, who instead emphasized the positive aspects of female religious devotion, recruiting them for the veneration of Mary. It is characteristic to find Kramer—a persecution specialist whose obsessions might be described in terms of “purity and danger”—engaged in an inquisition in Augsburg against women who desired the Eucharist too frequently, who were in turn defended by a local supporter of Sprenger (Koeniger 1923). The Malleus Maleficarum was divided into three parts. The first treated theological issues and the second practical problems; the third offered advice on legal procedures, referring constantly to the author’s extensive experience with witchcraft trials. The first part of the original edition (fols. 4r–43r) on theological questions, designed to prove the reality and danger of witchcraft, was interesting in several respects and showed Kramer’s erudition as an educated Dominican. Founded upon Augustine and Aquinas, its description of the crime of witchcraft was entirely conventional: witches could not themselves harm anyone through magic, but their abilities derived from a contract with a demon, which in turn was empowered by God. Both the permissio Dei (God’s permission), and (wo)man’s free will were crucial elements. At the core of witchcraft theory lay Augustine’s semiotic theory that demons and (wo)men communicated via signs, amplified here by Kramer’s perception that human deeds and natural phenomena were hardly ever what they appeared to be, but must rather be interpreted through a demonological theory of signs. Like postmodern theorists, Kramer concluded that human beings could never be certain about reality; any phenomenon could be different from what it appeared to be and could be a demonic delusion. In contrast to modern philosophers, who denied the reality of demons, Kramer denied the reality of reality. He suspected demons were omnipresent and (with God’s permission) extraordinarily powerful. Although witches believed they could do harm, it was actually demons who conducted supernatural interventions in order to fulfill their pact and to seduce them. The witch’s crime thus in fact became her desire to harm. But no secular law imposed the death penalty for mere intentions, so witchcraft must therefore be considered essentially as heresy. For Kramer, heresy and apostasy lay at the core of witchcraft; although the witches themselves might have thought otherwise, their basic crime was spiritual. His conclusions were subsequently developed through examples of specific aspects of witchcraft, including sexual intercourse between humans and demons (either succubi or incubi), shape shifting, the sacrifice of babies, and the preparation of witches’ unguents. According to Kramer, witches intended their harm to be real, although the demons actually did the damage by interfering in the real world in order to deceive the witches. Kramer’s conclusions were theologically correct but entailed serious practical contradictions. If harmful magic had no physical agent, it could not be prosecuted. If witches were seduced and deceived by demons, they became victims rather than perpetrators. If circumstantial evidence or direct observations could be discarded as devilish illusions (praestigia daemonum, as Johann Weyer later called them), witches could never be tried by a secular court because it was impossible to prove they had committed any crime whatsoever. Surprisingly, after denying the possibility of judging the reality of evidence, Kramer’s sharpest weapon (as he must have thought) was his reference to personal experience. Besides theological authorities, firsthand examples provided Kramer’s foremost evidence for the reality of witchcraft. Among roughly 250 examples in the Malleus, mostly from the Bible or ancient authors, at least 75 (nearly 30 percent) refer to recent events, which Kramer took from trustworthy contemporaries or from personal experience. About 10 percent of them came from Speyer or its immediate vicinity, further indication that Kramer completed the manuscript of the Malleus in this imperial city. Most of the rest came from Swabia, Alsace, or Tyrol; a few examples came from further abroad, usually towns with Dominican monasteries where Kramer had stayed (Rome, Cologne, Augsburg, Salzburg, Landshut in Bavaria). The second part of the original Malleus (fols. 43r–92v) was split into two sections. The first (2.1) -5- described how to protect oneself against witchcraft, specifically against impotence and infertility, weather making, and milk theft; the second (2.2) treated how bewitching could be cured. Again Kramer discussed demonically caused impotence, infertility, and weather magic, as well as love magic and demonic possession. The third part of the Malleus (fols. 92v–129v) explored the legal treatment of witches in great detail, recommending inquisitorial procedure as superior to trials based upon accusations, and paying attention to circumstantial evidence. In this part, Kramer literally copied large chunks of text from such inquisition manuals as Nicolas Eymeric’s Directorium Inquisitorum (Directory of Inquisitors) of 1376 to provide the necessary legal formulas for inexperienced judges. Pioneers of the intellectual history of demonology like Joseph Hansen emphasized that the Malleus contained almost nothing that could not be found in earlier demonologies or inquisitors’ manuals. Because Kramer was a Dominican doctor of theology and papal inquisitor, and considering the conditions under which he assembled the Malleus, that was hardly surprising. However, five points in his Malleus could be called original. First, it stressed that witchcraft was a real crime, not just a spiritual one, and that witches therefore must be prosecuted and deserve capital punishment. Among earlier inquisitors, this had been a minority position. Second, Kramer claimed that witchcraft is the worst of all crimes because it combines heresy, including apostasy and adoration of the Devil, with the most terrible secular crimes such as murder, theft, and sodomy. Again, this point was not entirely new, but Kramer focused attention on it. Third, because witchcraft was not only the worst of all crimes but also occult and difficult to trace, legal inhibitions must be abandoned. This idea was original in the sense that no serious lawyer in Europe normally suggested transgressing legal boundaries. His conflicts with local authorities had made Kramer keenly aware that this position was completely unacceptable under normal circumstances. Therefore, he resorted to the claim that witchcraft was an exceptional crime, in whose pursuit persecutory zeal was preferable to routine legality. Thus Kramer claimed the superiority of apocalyptic theology over law. Fourth, witches were primarily women. Despite the misogyny of the times, this idea was still uncommon in theology but was widespread in popular thought, so here Kramer’s personal obsessions might have gained some popular support. Finally, he believed that secular courts should prosecute the crime; here again, the inquisitor drew conclusions from his own experience because he knew how unpopular inquisitors often were in Europe north of the Alps. However, this idea was also paradoxical because secular courts were reluctant to prosecute spiritual crimes. A curious, literate public welcomed the Malleus Maleficarum as the first printed handbook of witch demonology and persecution. Although largely dependent on earlier theologians and inquisitorial handbooks, it was a fresh product by an erudite and experienced author. With twelve Latin editions printed in Germany and France between 1486 and 1523, The Hammer of Witches could be considered a success, although public interest was clearly strongest in the first ten years when the subject was still novel and the book was almost a best seller. Just after the Protestant Reformation, the demand for reprints broke down completely. Two generations later, with the Counter- Reformation accelerating, two Venetian printers saw a renewed demand for the Malleus in 1574 and 1576; in the 1580s, three new editions were printed in Protestant Frankfurt, followed by a fourth in 1600. It was France that became the stronghold of Malleus reprints after the Reformation. Demand grew in the 1580s, with two editions printed at Lyons in 1584 and 1595; after 1600, seven further editions were published at Lyons, the last in 1669. Significantly, the Malleus was never translated fully into any vernacular language during the period of witch hunting; the partial translation into Polish in 1614 omitted its legal parts. Its reception remained confined to highly educated theologians, physicians, and lawyers. Its contents had to be spread, if at all, through sermons. The upsurge of witchcraft trials in the early 1490s in central Europe has traditionally been interpreted as a result of the publication of the Malleus, and some incidents indicate that it had a direct impact. A monastic chronicler at Eberhardsklausen, on the Mosel River, reported that witches had plagued this region for some time, but great uncertainty about the matter had made it impossible to -6- prosecute them. Only after reading the Malleus did local authorities see how they could proceed against witches—which they did. Here we see a kind of “conversion experience,” but that was a rare example, and how the Malleus was generally received remains unclear (Rummel 1990). It is noteworthy that an early opposition publication was reprinted even more frequently in the 1490s. Ulrich Molitor, a lawyer for the bishop of Constance and a minor official at Archduke Sigmund’s court in Innsbruck, challenged the central assumptions of the Malleus. Molitor fashioned his text as a conversation between a fanatic believer in witchcraft, Molitor himself as an opponent, and Archduke Sigmund as the wise arbiter, always reaching reasonable conclusions and bluntly denying the possibility of the witches’ flight, the witches’ Sabbat, and shape shifting. Molitor merely repeated the traditional attitude of the Catholic Church and indeed promoted a conservative attitude toward sorcery. But this attitude had hitherto prevented witchcraft persecutions. Moreover, Molitor went one step further. By excluding theologians from his discourse, he implies that Dominicans or inquisitors should not interfere with legal questions. Illustrated by many exciting woodcuts, Molitor’s dialogue quickly went through ten reprints in the 1490s, including, unlike the Malleus, translations into vernacular German. Molitor presumably witnessed Kramer’s inquisitions in both the diocese of Constance and the diocese of Brixen. If this juris utriusque doctor (doctor of both laws, i.e., of canon and civil laws) opposed the Malleus, it was presumably because he knew its author and his illegal methods. And there are other examples of people rejecting Kramer’s views, either after reading the Malleus or after meeting him personally. In 1491, the imperial city of Nuremberg ordered a summary of the Malleus from Kramer because of some serious cases of sorcery; the famous publisher Anton Koberger, who printed three editions of the Malleus, was an immediate neighbor of Nuremberg’s Dominican convent. However, Nuremberg’s magistrates never followed Kramer’s advice, and it may not be coincidence that the ideas of the Malleus were ridiculed publicly by leading Nuremberg humanists like Willibald Pirckheimer. In the imperial city of Augsburg, where Kramer stayed when traveling between Italy and Alsace and where he became involved in serious quarrels with the local representative of Jacob Sprenger’s rosary brotherhood, the inquisitor was labeled a drunkard by the leading humanist Konrad Peutinger, and it may be no coincidence that the Malleus was never printed in this leading Upper German communications center. One of the most interesting reactions came from a close friend of the recently deceased Jacob Sprenger, who sharply rejected the idea that Sprenger had any connection to the Malleus (Klose 1972). By the early sixteenth century, the Malleus had clearly become a point of reference in intellectual debates: in 1509, defending a woman accused of witchcraft at Metz against the machinations of the local Dominican inquisitor, Agrippa von Nettesheim reacted equally sharply against the nonsense proposed in the Malleus. About the same time, Erasmus of Rotterdam satirized a zealous inquisitor in his Praise of Folly, and leading Italian jurist Andrea Alciati, labeled witch hunts in northern Italy as nova holocausta. It was certainly not an arbitrary decision of the Spanish Inquisition in 1526 to deny any authority to the Malleus. Rather than provoking the rising witchcraft persecutions at the end of the fifteenth century, the publication of the Malleus by this troublesome inquisitor may have simply tried to exploit preexisting popular fears. Between the 1480s and about 1520, witch burnings or small panic trials occurred not only in places where Dominican inquisitors incited the populace or where the town council had purchased a copy of the Malleus, but in many places throughout upper Italy, northern Spain, eastern France, Switzerland, western Germany, and the Burgundian Netherlands, even prior to its publication. In the decades between 1470 and 1520, there were severe mortality crises, and scapegoats were sought. In the early 1480s, plague rampaged widely through Upper Germany, Switzerland, and eastern France, and the original edition of the Malleus even linked witchcraft to plague in one particular case, in which a deceased witch had spread the disease from her grave (fol. 38r–38v). Imperial cities like Memmingen or Ravensburg lost much of their population in these years, and fears of sudden death were justifiably widespread. Not only witchcraft anxieties but popular piety in general soared, as we can see in the -7- iconographical representations of the “Dance of Death,” or in the rise of millennial fears, with the idea that humanity was living in the last age—a time characterized by bitter hardships and terrifying signs of the end of the world. Like other fundamentalist prophets, the author of the Malleus points to the book of Revelation in his Apologia to argue that the emergence of the witches’ sect was one sign of the imminence of the Antichrist. Wolfgang Behringer References and further reading: Ammann, Hartmann. 1890. “Der Innsbrucker Hexenprozess von 1485.” Zeitschrift des Ferdinandeums für Tirol und Vorarlberg 34: 1–87. ———. 1911. “ Eine Vorarbeit des Heinrich Institoris für den Malleus Maleficarum.” Mitteilungen des Instituts für Österreichische Geschichtsforschung, Ergänzungsband 8: 461–504. Anglo, Sydney. 1977. “Evident Authority and Authoritative Evidence: The Malleus Maleficarum.” Pp. 1–32 in The Damned Art: Essays in the Literature of Witchcraft. Edited by Sydney Anglo. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. Broedel, Hans Peter. 2003. The Malleus Maleficarum and the Construction of Witchcraft. Manchester, UK, and New York: Manchester University Press. Geldner, Ferdinand. 1964. “Das Rechnungsbuch des Speyrer Druckherrn, Verlegers und Grossbuchhändlers Peter Drach. Mit Einleitung, Erläuterungen und Identifizierungslisten.” Archiv für die Geschichte des Buchwesens 5 (reprint from 1962): 1–196. Hansen, Joseph. 1898. “Der Malleus maleficarum, seine Druckausgaben und die gefälschte Kölner Approbation vom Jahre 1487.” Westdeutsche Zeitschrift für Geschichte und Kunst 17: 119–168. ———. 1907a. “Heinrich Institoris, der Verfasser des Hexenhammers, und seine Tätigkeit an der Mosel im Jahre 1488.” Westdeutsche Zeitschrift für Geschichte und Kunst 26: 110–118. ———. 1907b. “Der Hexenhammer, seine Bedeutung und die gefälschte Kölner Approbation vom Jahre 1487.” Westdeutsche Zeitschrift für Geschichte und Kunst 26: 372–404. Jerouschek, Günter, ed. and trans. 1991. “‘Nürnberger Hexenhammer’ von Heinrich Kramer: Faksimile der Handschrift von 1491. Hildesheim, Zürich, and New York: Olms. ———, ed. 1992. Malleus Maleficarum [Speyer 1486]. Hildesheim: Olms. Klose, Hans-Christian. 1972. “Die angebliche Mitarbeit des Dominikaners Jakob Sprenger am Hexenhammer, nach einem alten Abdinghofer Brief.” Pp. 197–205 in Paderbornensis Ecclesia. Beiträge zur Geschichte des Erzbistums Paderborn. Festschrift für Lorenz Kardinal Jäger zum 80. Geburtstag. Edited by Paul-Werner Scheele. Paderborn: Schöningh. Koeniger, Albert Maria. 1923. Ein Inquisitionsprozess in Sachen der täglichen Kommunion. Bonn and Leipzig: Verlag Schröder. Kramer (Institoris), Heinrich. 2000. Der Hexenhammer: Malleus Maleficarum. Kommentierte Neuübersetzung. Edited and translated by Wolfgang Behringer, Günter Jerouschek, and Werner Tschacher. Introduction by Wolfgang Behringer and Günter Jerouschek. Munich: Deutscher Taschenbuch. ———. 2004. Der Hexenhammer: Malleus Maleficarum. Edited and translated by Wolfgang Behringer, Günter Jerouschek, and Werner Tschacher. 4th ed. Munich: Deutscher Taschenbuch. Kramer (Institoris), Heinrich, and James [sic] Sprenger. 1928. Malleus Maleficarum: The Classic Study of Witchcraft (1484). Edited by Montague Summers. London: Pushkin. Reprints, Arrow, 1971; Bracken Books, 1996. Also published as The Malleus Maleficarum by Heinrich Kramer and James [sic] Sprenger. Translated by Montague Summers. London: Peter Smith, 1990. -8- Müller, Karl Otto. 1910. “Heinrich Institoris, der Verfasser des Hexenhammers und seine Tätigkeit als Hexeninquisitor in Ravensburg im Herbst 1484.” Württembergische Vierteljahreshefte für Landesgeschichte NF 19: 397–417. Petersohn, Jürgen. 1988. “Konziliaristen und Hexen: Ein unbekannter Brief des Inquisitors Heinrich Institoris an Papst Sixtus IV. aus dem Jahr 1484.” Deutsches Archiv zur Erforschung des Mittelalters 44: 120–160. Rummel, Walter. 1990. “Gutenberg, der Teufel und die Muttergottes von Eberhardsklausen: Erste Hexenverfolgung im Trierer Land.” Pp. 91–117 in Ketzer, Zauberer, Hexen. Die Anfänge der europäischen Hexenverfolgungen. Edited by Andreas Blauert. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp. Schmauder, Andreas, ed. 2001. Frühe Hexenverfolgung in Ravensburg. Constance: UVK Verlagsgesellschaft. Schnyder, André. 1993. Malleus Maleficarum von Heinrich Institoris (alias Kramer), unter Mithilfe Jakob Sprengers aufgrund der dämonologischen Tradition zusammengestellt: Kommentar zur Wiedergabe des Erstdrucks von 1487 (Hain 9238). Göppingen: Kümmerle. Segl, Peter, ed. 1988. Der “Hexenhammer”: Entstehung und Umfall des “Malleus Maleficarum” von 1487. Cologne and Berlin: Böhlau. ———. 1991. “Malefice . . . non sunt . . . heretice nuncupande zu Heinrich Kramers Wiederlegung der Ansichten aliorum inquisitorum in diversis regnis hispanie.” Pp. 369–382 in Papsttum, Kirche und Recht im Mittelalter. Festschrift für Horst Fuhrmann zum 65. Edited by Hubert Mordek. Geburtstag, Tübingen: M. Niemeyer. Siemer, Polycarp M., O. P. 1936. Geschichte des Dominikanerklosters Sankt Magdalena in Augsburg (1225–1808). Vechta: Albertus-Magnus-Verlag der Dominikaner. Stephens, Walter. 2002. Demon Lovers: Witchcraft, Sex, and the Crisis of Belief. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. Wilson, Eric. 1990. “The Text and Context of the Malleus Maleficarum.” PhD diss., Cambridge University. -9-