Reading 3 - The Center for Developmental Science

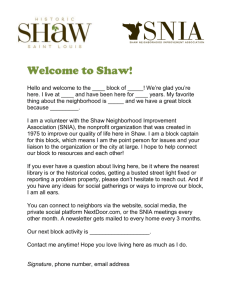

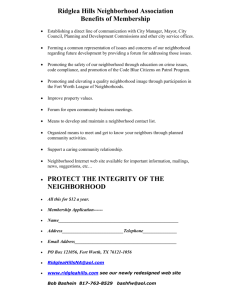

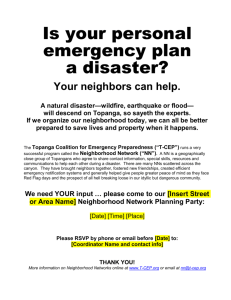

advertisement