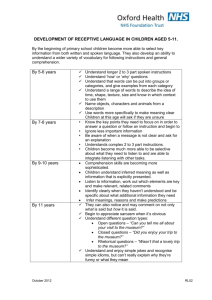

Accessing Enlightenment

advertisement