Workforce Planning Guide - Premier and Cabinet

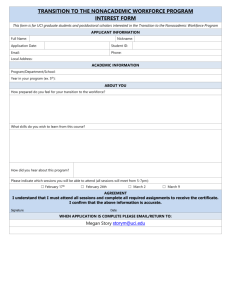

advertisement