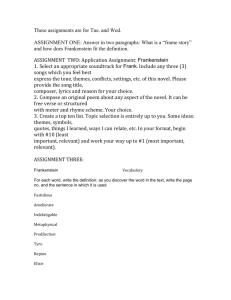

Frankenstein

advertisement