So You Want to Start a Campus Food Pantry?

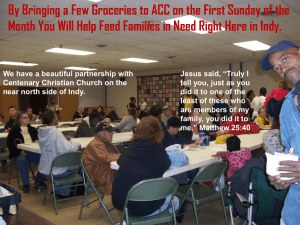

advertisement