chapter 1

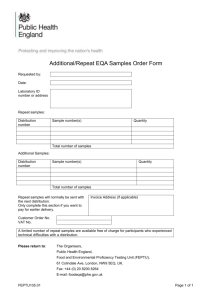

advertisement