H

9B12M046

Abstract for promotional use only. Full version available at www.iesep.com

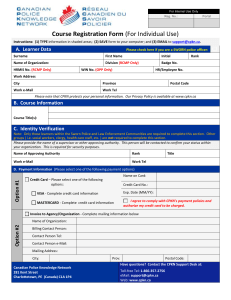

CANADIAN POLICE KNOWLEDGE NETWORK

Andrew MacVane wrote this case under the supervision of Professors Edward Gamble, Peter Moroz and Stewart Thornhill solely to

provide material for class discussion. The authors do not intend to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of a managerial

situation. The authors may have disguised certain names and other identifying information to protect confidentiality.

Richard Ivey School of Business Foundation prohibits any form of reproduction, storage or transmission without its written

permission. Reproduction of this material is not covered under authorization by any reproduction rights organization. To order copies

or request permission to reproduce materials, contact Ivey Publishing, Richard Ivey School of Business Foundation, The University

of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada, N6A 3K7; phone (519) 661-3208; fax (519) 661-3882; e-mail cases@ivey.uwo.ca.

Copyright © 2012, Richard Ivey School of Business Foundation

Version: 2012-04-30

When I go back to where CPKN [Canadian Police Knowledge Network] was three years

ago, that’s when we were just starting to figure out that we had to change our strategy

from not just going out and hounding police services on the value propositions of elearning, but to actually working with them on identifying and overcoming the adoption

barriers.

Typically, our biggest challenge is still cultural. The people who control training in these

organizations are trainers. They don’t want to switch. If it’s something new then they

don’t have an appetite for it. If it’s something that they’re doing now, it’s harder for

people to say “Hmm . . . what we’ve been doing for the last 25 years can be done better

this way.” So they just hang onto it. The big issue now is the biggest issue we’ve always

had, which is . . . our competition is not some other e-learning company; our competition

is the status quo.

— Sandy Sweet, president and CEO of Canadian Police Knowledge Network

OVERVIEW

The Canadian Police Knowledge Network (CPKN, was Canada’s leading provider of online training

solutions for police and law enforcement personnel. CPKN developed economical and engaging elearning courses primarily to meet the needs of front-line officers. Courses were hosted on CPKN’s

Learning Management System (LMS) and delivered via its website.1 Hosting e-learning courses through

the LMS allowed CPKN to authenticate all users, ensuring that sensitive course material did not enter the

public domain.

CPKN’s primary focus was on developing and delivering core-training courses that could be widely

administered yearly or as needed by clients. By taking a “build once, sell many times” approach, CPKN

hoped to ensure the long-term sustainability of its business model. Course prices were based on several

factors, including estimated user time to completion, media richness, funding sources and total

1

http://www.cpkn.ca

Distributed by IESE Publishing. If you need copies, please contact us: www.iesep.com. All rights reserved.

Page 2

9B12M046

development cost. Although courses were priced on an individual basis, CPKN also offered volume-based

discounting and course licensing agreements. In addition to general course design and delivery, CPKN

provided a range of other online learning services, including technical support, designated portals, custom

design and development, and consulting.

Abstract for promotional use only. Full version available at www.iesep.com

Despite recent success in increasing their user base and generating sufficient revenue to more than offset

expenses, CPKN remained underrepresented within police training as a whole. Some time ago, CPKN

partnered with the Alberta Solicitor General to deliver their Investigative Skills Education Program

(ISEP) for frontline officers in Alberta looking to move into investigative work. More recently CPKN had

entered into discussions with them to re-purpose this training and make it applicable to a national

audience.

E-LEARNING

E-learning, also known as online learning, refers to any form of learning conducted via networked

electronic formats that permitted interactive and/or multimedia components. E-learning was a

continuation of the concept of distance learning, which encompassed earlier technologies such as

correspondence courses, educational television and videoconferencing. Studies of distance learning had

concluded that the effectiveness of these older technologies were not significantly different from the

effectiveness of regular classroom learning.2 Some argued, however, that although distance learning did

not appear to be any more (or less) effective than traditional classroom learning, its lower cost made it a

viable and oftentimes more practical form of instruction.

In a 2010 report titled Evaluation of Evidence-Based Practices in Online Learning, the U.S. Department

of Education summarized the findings of 50 empirical studies of online learning In contrast to the findings

of prior research conducted on distance learning, these studies concluded that students using e-learning

performed better, on average, than students learning the same material through traditional face-to-face

instruction. Further, the studies found that instruction combining online and face-to-face elements had a

larger advantage relative to purely face-to-face instruction or purely online instruction.

These findings were central to CPKN’s value proposition. For many topics, it made both practical and

economic sense to teach the material online. CPKN had converted multi-day classroom training curricula

into online courses that could be completed within hours. Substantial savings could be realized by

sponsoring organizations; and the less time police officers spent in the classroom, the more time they

could spend performing their duties.

Not every topic of officer training lent itself to online learning. In firearms training, for example, although

many aspects of a gun could be taught in an online environment, the actual shooting of a gun could not be

taught online. Such subjects were ideal for a blend of e-learning and classroom-based instruction.

ORIGINS

In 2002, Holland College had spearheaded the creation of the Justice Knowledge Network (JKN), a

research and development (R&D) initiative to research and develop e-based training options for the

2

U.S. Department of Education, Office of Planning, Evaluation, and Policy Development, Evaluation of Evidence-Based

Practices in Online Learning: A Meta-Analysis and Review of Online Learning Studies, Washington, D.C., 2010.

http://www2.ed.gov/rschstat/eval/tech/evidence-based-practices/finalreport.pdf, accessed March 30, 2012.

Distributed by IESE Publishing. If you need copies, please contact us: www.iesep.com. All rights reserved.

Page 3

9B12M046

policing sector. At that time, JKN represented a consortium of public and private partners that, in

consultation with the Canadian policing community, shared experience and resources to develop and

deliver e-learning products for Canadian police and law enforcement personnel.

Abstract for promotional use only. Full version available at www.iesep.com

In 2004, JKN partnered with the Canadian policing community and National Research Council to create

the Canadian Police Knowledge Network, a not-for-profit organization for delivering JKN police training

products. Since that time, CPKN had become Canada’s leading provider of e-learning solutions for

police.

Sandy Sweet, president of CPKN, had been with the organization since its establishment in 2004. Sweet

had also been an advocate for the integration of enhanced learning technologies within Canada’s policing

community since 2002.Sweet held a bachelor’s degree in Business Administration from St. Francis

Xavier University and a master’s degree in Business Administration degree from Dalhousie University.

Sweet also served as JKN’s executive director and helped to broker the partnership agreement between

Holland College, the National Research Council and members of the Canadian policing sector to form

CPKN. As of March 2011, more than 60,500 learners had registered with CPKN and completed 161,000

course events.

PRODUCTS AND SERVICES

CPKN currently offered 67 courses (30 of which were offered in both French and English) to its

registered police users. Of these courses, 39 had been developed in-house, 17 had been developed by

police organizations such as the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) and 11 had been developed by

third-party non-police organizations, such as the Alzheimer Society of Canada. Courses covered a wide

range of topics, such as gang dynamics, basic investigation skills and recognizing emotionally disturbed

persons. All courses were delivered through CPKN’s secure LMS via its website. (For a list of all courses

offered by CPKN, see Exhibit 1). In addition to learner authentication (which prevented sensitive course

material from entering the public domain), the system provided learner tracking and reporting and could

synchronize training records with organizations’ existing human resources (HR) systems. CPKN also

offered a range of services, including technical support, designated portals, custom design and

development, and consulting.

Technical Support

CPKN’s bilingual support specialists were available by either phone or email to provide learners with

technical support. This service was available on weekdays from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m., Eastern Standard Time

(EST).

Designated Portals

Currently, CPKN itself had two specific general access portals: the “Sworn Officer” portal and the “Law

Enforcement Community” portal. Because each portal had separate user groups, rules and libraries of

courses available, CPKN could limit access to sensitive training content. The multi-portal functionality of

the LMS also enabled CPKN to create uniquely branded sections, or portals, for specific police services

or organizations. A designated portal enabled an organization to experience the advantages of an LMS

(tracking, reporting and user management) at a significantly lower cost than implementing an independent

Distributed by IESE Publishing. If you need copies, please contact us: www.iesep.com. All rights reserved.

Page 4

9B12M046

internal LMS. CPKN currently hosted designated portals for eight police services. For example, the

Toronto Police Service (TPS) had its own portal on CPKN’s LMS, which hosted both CPKN and internal

TPS training courses. This portal was accessible only to TPS members and was branded with the TPS

logo and service colours.

Abstract for promotional use only. Full version available at www.iesep.com

Custom Design and Development

Although custom courseware development was not part of CPKN’s core business, it represented potential

avenues for increased revenues. Using highly defined and replicable development processes, CPKN could

either design and develop a full course or customize an existing course to meet the needs of a specific

organization. However, CPKN had a limited capacity to take on custom development and typically did so

mainly to drive adoption of e-learning in specific markets and, subsequently, to increase future purchases

of its catalogue courseware. In a recent example of custom design and development, INTERPOL

commissioned CPKN to repurpose one of its courses to meet the organization’s specific needs. The

success of this agreement led to a multi-year contract whereby CPKN would develop and deliver 10

custom courses for INTERPOL employees.

Consulting

CPKN was also available to consult with organizations on a wide variety of online training issues,

including infrastructure requirements, program integration, knowledge management and needs

assessments. Similar to custom design and development, consulting represented a potential avenue for

increased revenues but was not considered part of CPKN’s core business. The primary purpose of

consulting was to drive adoption of e-learning in specific markets and, subsequently, to increase future

purchases of CPKN’s catalogue courseware.

Governance

CPKN was governed by a volunteer board of directors that established strategic priorities (see next

section) and oversaw the management of the organization. Currently, CPKN had 14 board members who

were primarily senior-level policing professionals from police services and training institutions across

Canada. Board members were also instrumental in promoting CPKN within their respective organizations

and among their peers.

CPKN also relied on the expertise, advice and guidance of a National Advisory Group that provided input

on an operational level. The National Advisory Group comprised volunteer members representing various

police and law enforcement organizations across Canada. This group had been instrumental in identifying

both trends within the police training community and areas of research that needed to be explored to

further meet CPKN’s organizational objectives.

Strategic Priorities

To be an integral and valued training and learning partner for Canadian and international

law enforcement agencies and related public safety organizations.

— CPKN Vision Statement

Distributed by IESE Publishing. If you need copies, please contact us: www.iesep.com. All rights reserved.