Transparency and Policy Implementation

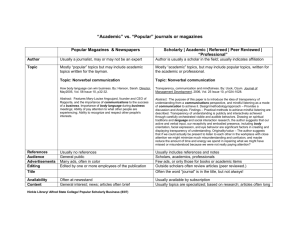

advertisement