Mechanical Properties: Chapter 7.

Chapter 7

Highlights:

1. Understand the basic concepts of engineering stress and strain, yield strength, tensile strength,

Young's(elastic) modulus, ductility, toughness, resilience, true stress and true strain, strain exponent, and know the difference between elastic and plastic deformation.

2. Understand what a stress-strain curve is and what information it contains about materials properties.

Be able to identify and/or calculate all the properties in #1 from a stress-strain curve, both in the elastic and plastic (before necking) regions.

3. Understand how the mechanical behavior of ceramics differs from that of metals. Be able to numerically manipulate the flexural strength and the effect of porosity on mechanical strength.

4. Understand how the mechanical behavior of polymers differs from that of metals. Understand and be able to numerically manipulate the viscoelastic modulus.

Notes:

Show Figures 7.1 to 7.4.

Define engineering stress and strain (tension and compression):

Engineerin g stress =

σ

=

F

A

0

Engineerin g strain =

ε

= l i

l

0

=

∆ l l

0 l

0

For shear stress,

Shear

Shear strain

= stress

γ

= tan

θ

= τ

F

=

A

0

(

θ is strain angle)

As shown in Figure 7.4, and described in Equations 7.4a and 7.4b, an applied axial force can be geometrically decomposed into tensile and shear components.

Stress-strain test: slowly increase stress and measure strain until the material fractures (show Figures 7.2, 7.3,

7.5, 7.10-12).

These tests are usually performed in tension. In the linear portion of the curve, Hooke's law is obeyed, σ =

Eε. E is called the modulus of elasticity, or Young's modulus, and is a property of the material. The units of

E are psi or MPa, remembering that Pa=N/m

2

. Typical values for E are given in Table 7.1 for metals, ceramics and polymers.

A similar relationship can be written for compressive, shear, and torsional loads. For shear stress,

τ

= G

γ

G is the shear modulus and is a property of the material.

On an atomic scale, lengthening (compressing) a specimen during tensile (compressive) loading results in lengthening (shortening) of atomic bonds. Young's modulus is a measure of the resistance to separation of adjacent atoms.

Youngs modulus

∝

dF dr r

0

Show Figure 7.7 and Table 7.1.

High E- W and Ni, low E- Mg, Al,

Au, Ag.

Show Table 3.7. E can be different in different directions, and this reflects the different atomic densities in different planes and directions.

When there is not a significant linear portion of an engineering stressstrain diagram, the secant and tangent modulus are sometimes employed.

Show Figure 7.6. The tangent modulus is the slope of the stressstrain curve at one particular point, while the secant modulus is the slope of a secant drawn from the origin to a particular point on the stressstrain curve.

By common sense, tensile strain in the z direction should yield compressive strain in the x and y directions.

Show F igure 7.9. ε x

=ε y

. Define Poisson's ratio υ

ν

= -

ε

ε z x

= -

ε

ε y z

υ=0.25-0.35 for most metals, and is again a property of the material. It can be shown that

E = 2G(1 +

ν

)

G

≈

0.4E for most metals.

The following analogies illustrate the differences between the linear and nonlinear portions of a stress-strain curve:

Hooke's law

→

Nonlinear σ-ε→

Bonds stretched

→

Bonds broken

→

Elastic deformation

→

Plastic deformation

→

No permanent damage

Permanent damage

Example Problem

A cylindrical steel bar 10 mm in diameter is to be elastically deformed. Using the data in Table 7.1, determine the force needed to produce a reduction of 3x10

-3

mm in the diameter.

From Table 7.1, E = 207 GPa and

ν

= 0.30. We are given information about the desired radial strain:

ε r

=

3 x 10

−

3 mm

10 mm

=

3 x 10

−

4

This can be related to the axial strain by the definition of Poisson’s ratio, eq. 7.8:

ε z

=

ε

υ r

=

3 x 10

−

4

=

1 x 10

−

3

0 .

30

Now use Hooke’s law, eq. 7.5, to determine the stress that must be applied:

σ =

E

ε =

( 207 GPa )

(

1 x 10

−

3

)

=

0 .

207 GPa

=

207 MPa

From the definition of stress, eq. 7.3,

F

= σ

A

0

=

207 x 10

6

Pa

π

4

( 0 .

01 m )

2 =

1 .

63 x 10

4

N

Tensile Properties of Materials:

Show a stress-strain curve, Figure 7.12. We will now digress for a while but eventually return to this figure and try to understand it and extract useful information. The linear portion of this curve undergoes elastic deformation (linear σ-ε), which disappears after the stress is removed. In other words, it is reversible. When the stress exceeds the linear portion of the stress-strain curve, permanent (irreversible) plastic deformation occurs.

Plastic deformation

Plastic deformation usually occurs near ε ≈

0.005 for metals. When Hooke's law fails, the material undergoes plastic deformation. Show Figure 7.10. Either 7.10a or 7.10b can occur, usually 7.10a.

Since plastic deformation involves atomic-level breaking of bonds and reforming of new ones, it is irreversible.

We want to be able to define unambiguously when a material yields , when it is permanently damaged. Show

Figure 7.10a, focusing on point P. This is the proportional limit, where the stress-strain curve deviates from linearity. But this is ambiguous.

Usually the stress-strain curve deviates from linearity quite gradually, so we need to define an arbitrary but universal definition of the elastic region. Starting from point σ=0, ε=0.002, draw a parallel line to the linear portion of the stress-strain curve. The stress at which this line intersects with the stress-strain curve is called the yield strength,

σ y

. This is one measure of a material's strength, its ability to resist plastic (permanent) deformation. In the case of Figure 7.10b the yield strength is the lower yield point.

Show Figure 7.11. The tensile strength is defined as the maximum stress prior to fracture. After M,

"necking" occurs, the cross-sectional area shrinks abruptly. The ductility is defined as the % plastic deformation at fracture.

Ductility =

l f l

l

0

0

x100

A low ductility material is brittle. Show Figure 7.13.

Resilience is the capability of a material to absorb energy when it is deformed elastically. The modulus of resilience U r

is

U r

=

ε y

∫

σ d

ε

0 where ε y

is the strain at fracture. Show Figure 7.15. For linear stress-strain curve,

U r

=

1

2

σ y

ε y

=

σ 2 y

2E

Toughness is the ability of a material to absorb energy up to fracture. It is defined by the same integral as U r

above, but the upper limit of integration is now fracture instead of yielding. Show

Table 7.3. High ductility corresponds somewhat with low strength.

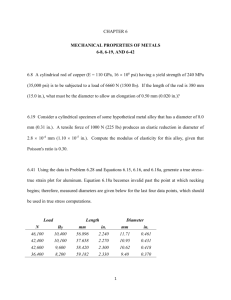

Example Problem

For a given set of data, which I will not reproduce here, you should be able to: a) Create a plot of engineering stress versus engineering strain, b) determine the elastic modulus, c) determine the yield strength, d) determine the tensile strength, e) determine the ductility, and f) determine the modulus of resilience. a) The plots below were obtained by taking:

σ

( Pa )

=

F

π

( N )

D

2

4

=

π

4

(

12 .

8

F ( N ) x 10

−

3 m

2

)

=

7771 .

2 F ( N )

ε = l i

− l

0 l

0

= l i

−

50 .

8

50 .

8

3.000e8

2.000e8

1.000e8

0.000e0

0.00

0.05

0.10

0.15

Strain b) The elastic modulus is taken as the slope of the linear portion of the curve. Looking at the 2 nd

plot, which focuses on the linear portion of the curve, take the average slope only from the 1 st

four points.

This yields: d) e) c)

E

=

σ

ε

=

5 .

696 x 10

7

Pa

0 .

00100

=

1 .

173 x 10

8

Pa

0 .

00200

=

1 .

795 x 10

8

Pa

Taking the average of these 4 values yields E =5.88x10

10

Pa.

0 .

00298

=

2 .

362 x 10

8

0 .

00398

Pa

On the 2 nd

plot, draw a line from

ε

= 0.002 with a slope of E = 5.88x10

10

Pa. The intersection of this line with the

σ

-

ε

curve gives

σ y

= 2.8x10

8

Pa.

From the 1 st

plot, the maximum in

σ

is the tensile strength = 3.7x10

8

Pa.

From the 1 st

plot, the strain at failure is about 0.145, subtract out the elastic strain (

≅

0.005) to get the plastic strain of 0.14. Thus the ductility is 14%.

f) Determine the modulus of resilience from equation 7.14:

U r

=

σ

2 y =

(

2 .

8 x 10

8

Pa

)

2

2 ( 5 .

88 x 10

10

Pa )

=

6 .

67 x 10

5

Pa

2 E

Elastic recovery after plastic deformation:

Show figure 7.17 and discuss.

True Stress and Strain:

True stress(σ

T

) and true strain(ε

T

) are defined similarly to engineering stress and strain.

ε

T

= ln

l l

0 i

σ

T

=

F

A i

=

Force

Instantane ous area l i is the instantane ous length

If volume is conserved, then A i l i

= A

0 l

0

and

σ

T

=

σ

(1 +

ε

ε

T

= ln (1 +

ε

)

)

The above two equations are only true until necking. After necking, true stress and true strain can only be

determined by actual measurements. Show Figure 7.16, where the true stress is corrected to account for nontensile components.

For some metals, from the onset of plastic deformation to the point at which necking begins, the true stress is approximately:

σ

T

=

K

ε

T n

K and n, the strain hardening exponent, vary across different metals and alloys.

Example Problem

You are given that just prior to necking, (

σ

,

ε

) = (235 MPa, 0.194) and (250 MPa, 0.296). What value of

σ will produce

ε

= 0.25. In order to use equation (7.19), we need to convert from engineering stress and strain to true stress and strain. From equations (7.18)

σ

1

T

= σ

( 1

+ ε

)

σ 2

T

= σ

( 1

+ ε

)

=

=

280 .

59 MPa

324 MPa

ε

1

T

= ln ( 1

+ ε

)

=

0 .

1773

ε

2

T

= ln ( 1

+ ε

)

=

0 .

2593

ε 3

T

= ln ( 1

+ ε

)

=

0 .

2231

You need to use equation (7.19) to setup two equations with two unknowns. Taking the ln of both sides: ln

σ

T

= ln K

+ n ln

ε

T ln ( 324 MPa )

= ln K

+ n ln ( 0 .

2593 )

ln ( 280 .

59 MPa )

Subtracting the 2 nd

from the 1 st

= ln K

+ n ln ( 0 .

1773 ) ln

324

= n ln

280 .

59 n

=

0 .

378

0 .

2593

0 .

1773

Substituting back into above: ln ( 280 .

59 MPa ) ln K

=

6

= ln K

+

( 0 .

378 ) ln ( 0 .

1773 )

.

291 or K

=

540 MPa

Now find where

ε

T

is 0.2231:

σ

T

=

K

ε

T n

σ

T

=

Convert back to engineering stress:

σ =

1

σ

+

T

ε

=

1

+

( 540 MPa ) ( 0 .

2231 )

0 .

378

306 .

3 MPa

0 .

25

=

=

306 .

3 MPa

245 MPa

Mechanical behavior: Ceramics

Ceramic materials are less mechanically useful than metals because they are generally quite brittle. Their mechanical strength is not normally assessed by tensile stress-strain measurements. It is extremely difficult to prepare the proper sample geometry, the samples generally crack when gripped, and their strain at failure is too small to accurately measure. Show Figure 7.19. For these reasons, the strength of ceramic materials is normally assessed by a traverse bending test. Show Figure 7.18. The failure point is described by the flexural strength (σ fs

), also known as the modulus of rupture(σ mr

). For rectangular cross sections,

σ fs

=

3 F

2b d f

2

L and for circular cross-sections:

σ fs

=

F

π f

L

R

3

Example Problem

A 3-point bending test is performed on Al

2

O

3

with a circular cross-section of radius 3.5 mm. The specimen fractures at a load of 950 N when the support points are 50 mm apart. Consider a square sample of the same material with a square cross-section of 12mm on each edge. If the support points are 40 mm apart, at what load will the sample fracture?

First, determine the flexural strength of this material from equation (7.20b):

σ fs

=

F

π f

R

L

3

=

( 950

π

N )( 50 x 10

−

3

( 3 .

5 x 10

−

3 m )

3 m )

=

3 .

53 x 10

8

Pa

Now determine the failure force from equation (7.20a):

F

=

2 bd

2

σ

3 L fs =

2 ( 12 x 10

−

3 m )

3

( 3 .

53 x 10

8

3 ( 40 x 10

−

3 m )

Pa )

=

10 , 170 N

Ceramic solids are often fabricated by compaction or foaming of ceramic particles. In this case, the ceramic solid may have considerable porosity, which degrades its strength. The modulus of elasticity (E) and the flexural strength (

σ fs

) depend on the volume fraction porosity (P) according to:

E

=

E

0

(

1

−

1 .

9 P

+

0 .

9 P 2

)

σ fs

= σ

0 exp(

− nP ) where

σ

0

and n are experimental constants.

Example Problem

Using the data in Table 7.2, a) a) Determine the flexural strength of nonporous MgO assuming n = 3.75 b) Calculate the volume fraction porosity when

σ fs

= 62 MPa.

Taking the ln of both sides of equation 7.22: ln

σ fs

= ln

σ

0

− nP

From Table 7.2,

σ fs

= 105MPa with 5% porosity, so ln ( 105 MPa )

σ

ln

0

σ

=

0

== ln

σ

0

==

4 .

841

−

( 3 .

75 )( 0 .

05 )

127 MPa

b) Rearranging the above equation:

P

= ln

σ

0

− ln

σ fs n

P

=

4 .

841

− ln ( 62 MPa )

=

0 .

190 or 19 vol .%

3 .

75

Note that 5% porosity reduces

σ fs

by 17%, and 19% porosity reduces

σ fs

by 51%.

Mechanical behavior: Polymers

Typical stress-strain diagrams for polymers are shown in Figure 7.22. The behavior ranges from strong and brittle (curve A) to rubbery (curve C). The mechanical behavior of polymers is far more temperaturedependent than that of metals and polymers. Show Figure 7.24. Polymethyl methylacrylate behaves like a brittle metal at low temperature, but like an elastomer (rubber band) at low temperature. At intermediate temperatures, this polymer behaves like a viscoelastic material, which combines the behavior of a viscous and an elastic material. The most famous viscoelastic material is silly putty, which is intermediate between a liquid and a solid. Show Figure 7.26, which shows the strain behavior with time following instantaneous application of a load.

Alternatively, one can study the mechanical behavior of a viscoelastic material at constant strain, in which case the stress that is initially applied will gradually decrease. Show Figure 7.27, which shows the stress as a function of time and temperature. How can we compare different materials?? One way is to choose an arbitrary time (10 sec is common) and define the relaxation modulus, E r

(t), at that time:

E r

( t )

=

σ

( t )

ε

0

Remember that the value of E r

(10) depends on the temperature. Show Figure 7.27 again.

Safety factor

Engineering with a safety factor accounts for material variability, nonideal conditions, human error, etc. and is common engineering practice. The working stress (

σ w

) is reduced from the yield stress (

σ y

) by the safety factor (N) according to:

σ w

=

σ

N y

The safety factor N is commonly taken as 2.