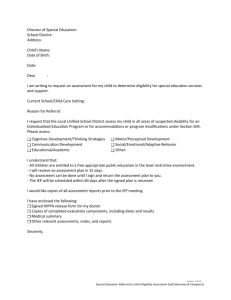

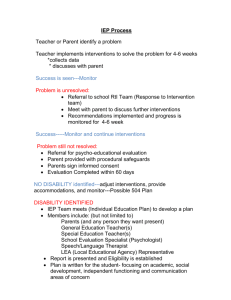

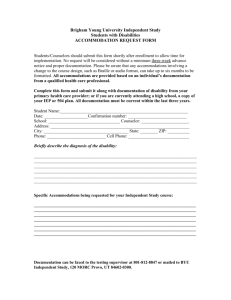

Delivery of Special Services

advertisement