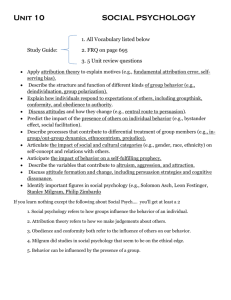

Attribution Theories: How People Make Sense of Behavior

advertisement