Corporate Taxation

advertisement

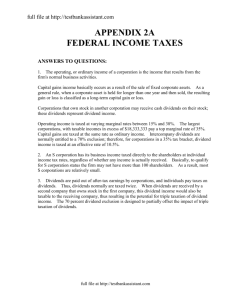

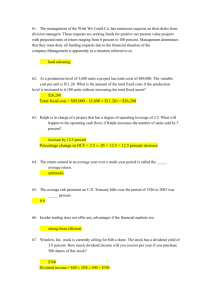

Corporate Taxation Introduction The taxation of corporations is an important topic for anyone involved in financial and estate planning. A well thought out financial or estate plan could become a nightmare in a situation where the principals of corporate taxation are not fully integrated with the principals of personal and estate taxation. This Tax Topic discusses the fundamental aspects of corporate taxation and examines how these concepts integrate with personal and estate taxation. For details on the taxation of life insurance in the corporate context refer to the Tax Topic, “Corporate Owned Life Insurance – Tax Considerations”. Calculation of Taxable Income For financial statement purposes, a corporation generally calculates its net income using either Accounting Standards for Private Enterprises or International Financial Reporting Standards. Adjustments are then made for items that are treated differently for accounting than for tax purposes. it is important to understand that “net income” as stated in the financial statements is generally not equal to “taxable income”. After making certain adjustments, the corporation’s taxable income is determined. Expenses that are non-deductible for tax are added back to accounting net income. For example, accounting depreciation, a portion of meals and entertainment expenses, and in all but limited circumstances, life insurance premiums, are added back to net income. Deductions allowed by income tax legislation are subtracted from accounting net income, including capital cost allowance and collateral insurance premiums. Other non-taxable receipts are also subtracted from net income, including dividends received from other Canadian corporations and life insurance proceeds. A detailed analysis of these adjustments is beyond the scope of this Tax Topic; however, for a detailed discussion of accounting for life insurance refer to the Tax Topic, “Accounting for Corporate Owned Life Insurance and Critical Illness Insurance”. Tax Classification of Corporations The taxation of a particular company is impacted by the classification of that corporation for tax purposes. The three main types of corporations for tax purposes are: public corporations, private corporations and Canadian controlled private corporations (“CCPCs”). A public corporation is one with shares listed on a prescribed stock exchange. A private corporation is a Canadian resident corporation that is not a public corporation. A CCPC is a private corporation that is not controlled directly or indirectly by one or more non-residents. Many Canadian owner-managed companies are CCPC’s. Tax Rates The basic federal income tax levied on most corporations under Part I of the Income Tax Act (the “Act”) is currently 38%. The federal tax payable is reduced by 10% of the corporation’s taxable income earned in a province or territory in Canada. The reduction is called the federal abatement and is intended to recognize the provincial tax the corporation pays. There are several other reductions to the Part I rate depending on the type of corporation and the type of income earned: Small Business Deduction (17%) The Small Business Deduction (“SBD”) reduces the tax rate on eligible income by 17% (eligibility requirements for the SBD are discussed below); Manufacturing and Processing Profits Deduction (13%) The Manufacturing and Processing (“M&P”) deduction applies to manufacturing and processing profits. The M&P deduction cannot be claimed on income eligible for the SBD. Note that the M&P deduction is at the same rate as the general rate reduction discussed below (i.e., 13%); therefore, there is no longer an advantage to claiming the M&P deduction unless there is also a provincial deduction available. Saskatchewan, Ontario, Newfoundland, and the Yukon are the only provinces that still have a M&P deduction available; and General Rate Reduction (13%) Currently, there is a general rate reduction of 13% on “full rate taxable income”. “Full rate taxable income” (as defined in subsection 123.4 of the Act) is essentially income that is not eligible for another tax reduction such as the SBD or the M&P deduction. For CCPCs, investment income is excluded from full rate taxable income and does not qualify for the 13% rate reduction. Provincial or territorial tax is added to the federal tax based on the province or territory in which the corporation conducts its business. If the corporation does business in more than one province, a formula allocates the income among the provinces. All of the provinces have a small business deduction that parallels the Federal SBD, but the rates and thresholds are different for each province. Small Business Deduction The 17% SBD is available to CCPCs on income from an “active business carried on by a corporation” that does not exceed the “annual business limit”. The overall federal rate of tax on income subject to the small business deduction is 11% (15.5% with Ontario provincial tax). Active income in excess of the annual business limit is subject to tax at an overall federal rate of 15% (26.5% with Ontario provincial tax for the 2014 calendar year.) (See Appendix A for rate calculations). “Active business carried on by a corporation” is defined in subparagraph 125(7) of the Act as “any business carried on by a corporation other than a specified investment business or a personal services business and includes an adventure or concern in the nature of trade.” The basic notion behind this definition is that there must be effort exerted to earn the income and therefore includes most business income. “Personal Services Business” (“PSB”) income is excluded from the definition of “active business income” and is not eligible for the SBD or the General Rate Reduction. A corporation is carrying on a personal services business if it meets two criteria. Firstly, the corporation provides the services of its employee to a third party where, if the corporation did not exist, it would be reasonable to regard the individual as an employee of the third party. Secondly, the employee, or someone who does not deal at arm’s length with the employee, owns, directly or indirectly, 10% or more of the shares of the corporation. A PSB is often referred to as an “incorporated employee”. There are two exceptions provided: a PSB will not be carrying on a personal services business if it employs more than five fulltime employees or if the services are provided to an associated corporation. A “specified investment business” generally means a business that derives income from property (including interest, dividends, rents and royalties). However, in situations where the corporation employs more than 5 full-time employees the income is not considered to be from a specified investment business and qualifies as active business income. It appears that the theory behind this legislation is that if the corporation is large enough to employ more than five full-time employees, there is effort being exerted to earn the investment income. For clients with a large rental operation, 2 there may be an opportunity to incorporate and take advantage of the SBD if there are more than five full-time employees. It should also be noted that interest, rents and royalties received by a corporation from an associated corporation are deemed to be active business income by subsection 129(6) of the Act provided that the payer deducted the amount in determining income from an active business. The Federal annual business limit is currently $500,000. The provincial limits for 2014 are also $500,000 with the exception of Manitoba and Nova Scotia with provincial limits of $425,000 and $350,000 respectively. As a result, for income levels between the federal threshold and the provincial threshold in these two provinces, the tax rate is a blend of the lower small business federal rate and the higher provincial general rate. The annual business limit must be shared among all associated corporations. A detailed discussion on associated corporations is beyond the scope of this Tax Topic. However, a basic rule of thumb is that if there is common control (i.e., the same shareholder owns more than 50% of the shares of each of the companies), the companies are associated. Therefore, a shareholder is not able to multiply the small business limit by simply incorporating another company. The Federal SBD begins to be phased out where the corporation’s (or associated corporations’) “taxable capital” for the immediately preceding year exceeds $10 million and is eliminated where the corporation’s “taxable capital” exceeds $15 million. “Taxable capital” for this purpose is a complex calculation, but generally includes the capital, retained earnings and debt of the corporation less an investment allowance. The Federal SBD is available to many sizable corporations (i.e., those with taxable capital under $10 million) carrying on an active business. In prior years, Ontario clawed back the benefits of the SBD by imposing a surtax of 4.25% on income in excess of the Ontario Small Business Limit. This surtax was eliminated on July 1, 2010. Investment Income Investment income is income earned from property and is commonly referred to as inactive or passive income. Investment income typically includes: rents, interest, dividends and royalties earned. Although capital gains are not included in the term “property income” as used in the Act, the taxable portion of capital gains (net of capital losses) is included in investment income (as defined in subsection 129(4) of the Act). Note that only one-half of capital gains are included in taxable income; therefore, the effective rate of tax on capital gains is one-half the rate of other investment income. Investment income (other than dividends received from a Canadian corporation) is subject to basic Part I tax. For a non-CCPC that is not an investment corporation, investment income is taxed in the same manner and at the same rate as active income (i.e., 38% general rate less 10% abatement less 13% general rate reduction.) However, investment income earned by a CCPC is not eligible for the 17% SBD or the 13% general rate reduction. In addition, investment income in a CCPC is subject to an “additional refundable tax” of 6.67%. This means that the overall Federal tax rate applicable to investment income earned by a CCPC is approximately 35% (approximately 46% with provincial tax) (see Appendix A). A high rate of tax is imposed on investment income earned by a CCPC in order to prevent individuals from deferring tax on investments by incorporating an investment portfolio. However, it is not the intent to unduly tax investment income earned by a corporation on an integrated basis (i.e., when it is ultimately flowed through to the shareholder). Therefore, to ensure that the tax system functions as desired, the Act utilizes a refundable tax system. A portion of the Federal Part I tax paid by a CCPC (26.67% of the taxable investment income) is refundable when the income is distributed to a shareholder in the form of a taxable dividend. The refundable tax is tracked in a special account called the refundable dividend tax on hand (“RDTOH”) account (discussed below). Dividends received from Canadian corporations Most corporations can deduct dividends received from Canadian corporations from net income to arrive at their taxable income. These dividends are therefore not generally subject to Part I tax but will be subject to a special refundable tax (Part IV tax) calculated as 33% of the dividend. If the dividend is received from a connected corporation, the recipient corporation will only pay Part IV tax 3 to the extent the connected payer corporation received a dividend refund (discussed below). (Generally, corporations are connected where there is common control or the payee corporation owns more than 10% of the votes and value of the payor corporation.) Therefore, generally, dividends can flow tax-free between connected corporations. Dividends received from Canadian corporations that are not connected (often called “portfolio dividends”) are subject to Part IV tax. Part IV tax paid is added to the RDTOH account and will be refunded as dividends are paid out of the corporation. Integration The corporate tax system for private corporations is intended to integrate with the personal tax system such that income earned in a corporation and distributed out to the shareholder(s) will be taxed on a combined basis at approximately the same rate as it would have been taxed if the shareholder had earned the income personally. The theory is that an individual should be indifferent (for tax purposes) between holding an investment portfolio or business personally versus holding it through a corporation. The SBD, the RDTOH account and the capital dividend account (“CDA”) are mechanisms built into the tax system to make integration work with different types of income. Distributions from a Corporation Corporations can distribute cash or assets to shareholders in two ways: as salary/bonus or via a dividend. The basic difference between salary and dividends is that salary is paid out of pre-tax profits (i.e., salary is a tax deduction to the company) and is taxed at the shareholder level as employment income. Dividends are paid out of after-tax profits (i.e., the company does not receive a tax deduction); therefore, the company pays corporate tax on corporate profits and the shareholder pays tax when the profits are distributed as dividends. However, dividends receive preferential tax treatment at the personal level via the dividend tax credit mechanism. Shareholders in the top tax bracket pay tax on salary at a combined federal and provincial rate of approximately 46% whereas the top marginal rate applicable to eligible dividends ranges, depending on the province, from approximately 16% to 36% and from approximately 29% to 41% for ineligible dividends (taking into account both the dividend gross-up and the dividend tax credit). Note that only shareholders can receive dividends but salary can be paid to employees as well as shareholders who are also employees. Prior to 2006, there was only one dividend tax credit rate and one dividend gross-up rate. These rates were designed to offset corporate tax to the extent it had been paid at the small business income rate. As a result, integration failed when a corporation paid tax at the high rate. To correct this inequality, the government introduced two types of dividends (eligible and ineligible) corresponding with two levels of dividend tax credit and gross-up. Eligible dividends generally include dividends paid after 2005 by corporations resident in Canada from income that has been subject to tax at the general corporate income tax rate (i.e., income that is not eligible for the SBD and that is not investment income earned by a CCPC) and eligible dividends received by the corporation. There are complex rules governing the calculation of eligible dividends, but in general, most income generated in non-CCPCs will be available to be distributed as eligible dividends. Income generated in CCPCs will be available to be paid out as eligible dividends only to the extent that the corporation’s taxable income exceeds the federal small business limit. Investment income earned in a CCPC and income eligible for the SBD may be paid out as ineligible dividends. There are mechanisms in the tax systems that penalize shareholders trying to avoid tax on distributions from a corporation. For example, if the corporation pays for a shareholder’s personal expenses, the result is a taxable benefit to the shareholder. As discussed later, a shareholder benefit is not deductible to the corporation. Refundable Dividend Tax on Hand Account As discussed above, a portion of the Part I tax paid by a CCPC on investment income (26.67% of the taxable investment income), as well as the Part IV tax paid by a private corporation on portfolio dividends, is accumulated in the RDTOH account. The RDTOH is refunded to the company as the company pays taxable dividends to its shareholders. For every $3 in taxable dividends paid to the company’s shareholders, $1 of tax is refunded to the payer corporation to the extent of the company’s RDTOH account. This refund is referred to as the “dividend refund”. The balance in the RDTOH account at the end of a year equals the balance from the end of the previous year, plus refundable Part I tax and Part IV tax paid by the corporation in the year minus any dividend refund received by the corporation in the year. In this way, the RDTOH account “tracks” the refundable tax available to a corporation. If a dividend in excess of three times the RDTOH account is paid out, only the balance in 4 the RDTOH account may be received as a dividend refund. This is illustrated in the example at the bottom of Appendix B. Capital Dividend Account Integral to the principle of tax integration is recognizing that an amount that would have been tax-free if received directly by a shareholder should not be subject to tax if a private corporation receives it and flows it out to the shareholder. The CDA is a notional tax account created as a means of tracking these amounts for income tax purposes. The corporation can distribute non-taxable amounts to shareholders on a tax-free basis by paying a “capital dividend”. Capital dividends are ordinary dividends declared by the corporation, but which the corporation elects, for tax purposes, to be capital dividends. Capital dividends can only be paid to the extent that there is an amount in the CDA. When a capital dividend is paid, the CDA is reduced by the amount of the dividend. Note that because capital dividends are non-taxable, they do not result in RDTOH refunds. The amounts accumulated in the CDA include capital dividends received from other corporations, life insurance proceeds (to the extent the proceeds exceed the corporation’s adjusted cost basis of the policy) and the non-taxable portion of capital gains less the non-taxable portion of capital losses. As both individuals and corporations include only 50% of capital gains in taxable income and as both individuals and corporations receive life insurance proceeds tax-free, without the CDA mechanism the corporation would receive these items tax-free, but the shareholder would pay tax on them when they were distributed as dividends. All private corporations resident in Canada qualify for a CDA; there is no requirement that the corporation be a CCPC. Public corporations do not qualify for a CDA. Non-residents receiving capital dividends will likely pay tax on these dividends in their country of residence as well as Canadian withholding tax. For a detailed discussion of the CDA, refer to the “Capital Dividend Account” Tax Topic. Integration on Investment Income Appendix B illustrates how various types of investment income flow through a corporation and utilize the RDTOH account and CDA mechanisms. Note that Part IV tax paid with respect to dividends from Canadian corporations is fully refunded upon the payment of dividends. As a result, integration is perfectly achieved on dividends from Canadian corporations; that is, the income is taxed at exactly the same rate whether earned in a corporation and distributed to the shareholder or earned directly by an individual. The after-tax cash received by a shareholder when interest income and capital gains (or rents or royalties) are flowed through a corporation is almost equal to the amount of after-tax cash a shareholder would receive if the investment income were earned personally. However, in most provinces there is still an overall cost to earning investment income (other than Canadian eligible dividends) in a corporation and flowing the after-tax amounts out to the shareholders rather than owning the investments personally. Integration on Active Income To the extent the income of a CCPC is eligible for the SBD, the combined corporate and personal tax is approximately the same regardless of whether the earnings are distributed as salary or dividends. Before the introduction of the eligible dividend rules there was a much higher total tax burden when active income earned by a corporation not eligible for the SBD was distributed as a dividend rather than as salary and is still the case in provinces with relatively high tax rates on eligible dividends. This is because the corporation pays corporate tax at the high rate with no deduction for the dividends paid. The higher tax cost is the basis for the basic tax-planning principal of “bonusing down” to the annual business limit. If eligible dividend rates are high, to minimize the combined tax, a CCPC can pay a bonus to the shareholder-manager equal to the amount of income that it earns in excess of the annual business limit. The bonus provides the company with a deduction to reduce its income down to the small business limit, and therefore the income is taxed only at the shareholder’s personal tax rate applicable to employment income. In provinces where the tax rate on eligible dividends is very low, shareholder-managers may now prefer to leave all income earned in the corporation (including income taxed at the high rate) inside 5 the corporation and defer the personal tax incurred on distributing that income until some point in the future when it will be distributed as a dividend. At a dividend tax rate of 23%, assuming a corporate tax rate of 30%, there is no increase in the overall tax paid if the income is distributed as a dividend. In this case, because there is no additional tax cost, it is advantageous for the corporation to retain the earnings, so that it can defer the personal tax until the earnings are paid out of the corporation. Appendix C shows the taxation of active business income flowed through a corporation and distributed as dividends versus salary for three different scenarios: 1. Income eligible for the small business deduction (subject to 16% corporate tax) and distributed as an ineligible dividend (at a 33% dividend rate); 2. Income not eligible for the small business deduction (subject to 30% corporate tax) and distributed as an eligible dividend in a province with a low rate (23%); and 3. Income not eligible for the small business deduction (subject to 30% corporate tax) and distributed as an eligible dividend in a province with a high rate (30%). In all cases, there is a deferral advantage to leaving the income in the corporation rather than paying it all out as salary. The value of the deferral depends on how long the earnings are left in the corporation. At the rates shown in Appendix C, the following conclusions can be drawn: for income eligible for the SBD, there are tax savings on distributing the income as a dividend rather than as salary. As noted above, for income not eligible for the SBD, subject to a 23% dividend tax rate, there is no tax cost or savings on distributing the income as a dividend rather than salary. For income not eligible for the small business deduction, subject to a 30% dividend tax rate, there is a tax cost of 5% for distributing the income as a dividend rather than salary. In considering whether to pay corporate earnings out as salary/bonus now, or to retain the income in the corporation and pay it out later as a dividend, the tax cost of paying dividends (if any) must be compared to the benefit of the deferral. Conclusion There are a number of aspects to corporate taxation that are essential to understand when developing a financial or estate plan. The fundamental concepts of integrating personal and corporate tax provide the framework for structuring financial and estate plans and for comparing alternative plans. Last updated: November 2014 Tax, Retirement & Estate Planning Services at Manulife writes various publications on an ongoing basis. This team of accountants, lawyers and insurance professionals provides specialized information about legal issues, accounting and life insurance and their link to complex tax and estate planning solutions. These publications are distributed on the understanding that Manulife is not engaged in rendering legal, accounting or other professional advice. If legal or other expert assistance is required, the service of a competent professional should be sought. This information is for Advisor use only. It is not intended for clients. This document is protected by copyright. Reproduction is prohibited without Manulife's written permission. Manulife, the Block Design, the Four Cubes Design, and strong reliable trustworthy forward-thinking are trademarks of The Manufacturers Life Insurance Company and are used by it, and by its affiliates under license. 6 Appendix A Income Tax Rates for Corporations (2014) Active Business Income Eligible Not SBD M&P for SBD Eligible (1) Income General corporate rate Federal abatement Surtax General rate reduction Small business deduction M&P deduction Additional tax on investment income Provincial tax (Ontario calendar 2014 rate) Total 38.00% -10.00% 28.00% 0.00% 28.00% -17.00% 38.00% -10.00% 28.00% 0.00% 28.00% -13.00% 38.00% -10.00% 28.00% 0.00% 28.00% -13.00% Investment Income (2) CCPC Non-CCPC 38.00% -10.00% 28.00% 0.00% 28.00% 38.00% -10.00% 28.00% 0.00% 28.00% -13.00% 11.00% 15.00% 15.00% 6.67% 34.67% 15.00% 4.50% 11.50% 10.00% 11.50% 11.50% 15.50% 26.50% 25.00% 46.17% 26.50% (1) Applicable to companies not eligible for the small business deduction and income in excess of the annual business limit. The Federal annual business limit is currently $500,000. (2) Excluding Dividends from Canadian corporations. 7 Appendix B Investment Income - Sample Integration of Corporate and Personal Tax Systems Income Earned in a CCPC and paid to shareholder as a dividend Corporate Income Taxable Income for Part I (1) Corporate Part I Tax - (47%) (2) Corporate Part IV Tax - (33.33%) Cash Available for Dividend Dividend Refund (of RDTOH) (3) Net Cash Available for Dividend Less: Tax Free Capital Dividend Dividend from Cdn Corporation (not connected) $ 100,000 Interest $ (33,333) . Shareholder's Taxable Dividend Personal Tax on Dividend (33%) 100,000 100,000 (47,000) Capital Gains $ 100,000 50,000 (23,500) Total $ 300,000 150,000 (70,500) (33,333) 66,667 33,333 53,000 26,500 76,500 13,250 196,167 73,083 100,000 79,500 89,750 (50,000) 269,250 (50,000) 100,000 (33,000) 79,500 (26,235) 39,750 (13,118) 219,250 (72,353) $ 67,000 $ 53,265 $ 76,633 $ 196,898 Personal Income Personal Tax (4) $ 100,000 (33,000) $ 100,000 (46,000) $ 100,000 (23,000) $ 300,000 (102,000) Net After Tax Cash to Individual $ 67,000 $ 54,000 $ 77,000 $ 198,000 Net After Tax Cash to Shareholder Income Earned by an individual Summary of Tax Accounts (Total) Opening Balance Non-taxable portion of capital gains ($100,000 x 50%) Refundable portion of Part I tax paid ($150,000x26.67%) Refundable Part IV tax paid (from above) $ - $ 40,005 33,333 Balance before payment of dividends 73,338 Dividend refund received by corp (from above) Capital dividend paid by corp (from above) Closing Balance Capital Dividend Account RDTOH Account 50,000 (73,083) $ 255 50,000 (50,000) $ - (1) Capital gains are taxable based on a 50% inclusion rate (2) A portion of the Corporate Part I tax paid on investment income is refundable and goes into the RDTOH account. This portion is calculated as 26.67% of the investment income. (3) RDTOH refund is calculated as the lesser of the RDTOH account balance ($73,338) and 1/3 of the taxable dividend (1/3 x $219,250 = $73,083). Interest and Capital Gains will have RDTOH carryforward as there is not enough cash to pay a dividend and receive the full refund. (4) Assuming a 33% personal tax rate on dividends, and a 46% personal tax rate on other income. Appendix C Active Business Income - Integration Example Corporate Income Paid out as a Dividend Corporate Income With SBD Ineligible Dividends No SBD Eligible Dividends (low rate) $ 100,000 $ 100,000 Corporate Tax* (Federal & Provincial) (16,000) (@ 16%) No SBD Eligible Dividends (high rate) $ (30,000) (@ 30%) 100,000 (30,000) (@ 30%) Net After Tax Cash Available for Dividend 84,000 70,000 70,000 Dividend to Shareholder 84,000 70,000 70,000 Personal Tax* on Dividend Net After Tax Cash to Shareholder (27,720) (@ 33%) $ 56,280 (16,100) (@ 23%) $ 53,900 (21,000) (@ 30%) $ 49,000 Tax Rate 44% 46% 51% Tax deferred until distribution of dividend (total tax rate less corporate tax rate) 28% 16% 21% Corporate Income Paid out as Salary/Bonus Corporate Income $ 100,000 Salary paid to Shareholder $ 100,000 (100,000) Net After Tax Cash Available for Dividend $ (100,000) - 100,000 (100,000) - - Salary to Shareholder 100,000 100,000 100,000 Tax on Salary (46%) (46,000) (46,000) (46,000) Net After Tax Cash to Shareholder $ 54,000 $ 54,000 $ 54,000 Tax Rate 46% 46% 46% Tax savings (cost) of dividends vs salary 2% (0%) (5%) * Keep in mind that the corporate tax is paid when the income is earned in the corporation. However dividend tax is only paid when the corporation decides to distribute the funds at a future date, and thus may be deferred.