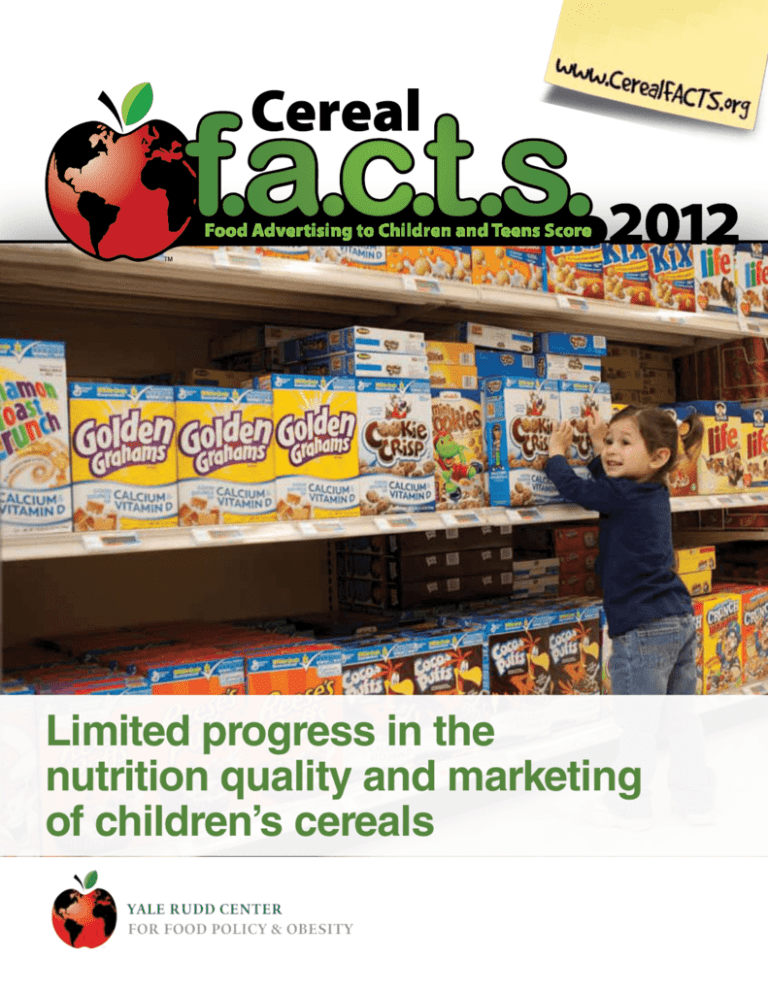

Limited progress in the nutrition quality and

advertisement