Romano-British Settlement and Land Use on the Avonmouth Levels

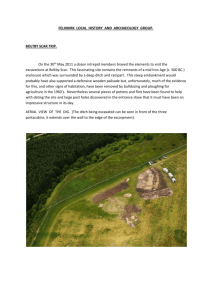

advertisement