The human development index and changes

advertisement

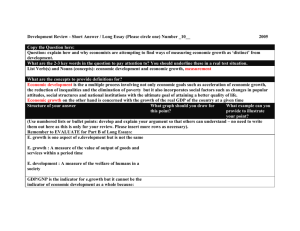

The Human Development Index. A better way of measuring welfare? Notes on Nick Crafts, ‘The human development index and changes in standard of living: some historical comparisons. European Review of Economic History, Vol 1, 1997,pp.299322. The HMI (Human Development Index) was initially sponsored by United Nations as an alternative or supplement to conventional GDP per head or employee measures of welfare. There is a deeper philosophical motivation behind it suggesting that GDP measures are to much focussed on the commodity basis of welfare, that is concentrating on the commodities an income can buy. An important aspect of welfare - as pointed out Amartya Sen and others are human capabilities which permit people not only to earn an income but to participate in political and social life, to defend personal dignity. The HDI which Crafts quantifies stretches over 120 years and includes per capita income , life expectancy as a measure of =value of life= and education. To understand the novelty of the HDI look at education. Schooling can contribute to welfare by improving earnings ( and hence growth of the economy). Assume now that R. Barro is right in finding no correlation between primary schooling and growth. We can still argue that primary schooling is a vital welfare indicator because it enhances human capabilities, for example to participate in political and social life and schooling improves the capacity to make informed choices for a citizen. Having said that it is important to note that there are no obvious way of weighting the components in the HDI and there is no good argument not to include additional indicators, such as political and civil rights, for example.(It is possible that some UN member states object to having political rights in the index, and after all HDI is a UN initiative). The three components, income, education and life expectancy are given equal weights in Crafts= article. For each component a number is calculated that can take a value not larger than 1, which implies that the highest value any nation can attain is 1. Life expectancy for a nation usually takes a value between a maximum and a minimum, say 44 years for US in 1870, the max set at 85 and the min at 25. The US value is calculated as (44-25)/(85-25) = 0.317. Early attempts to quantify HDI implicitly assumed that there was falling marginal utility of income to the effect that income above a critical threshold was discounted. Crafts also uses a HDI* in which this procedure is not used and the alternative expresses the income in a particular country as a percentage of the maximum at a given point in time: Australia in 1870 and 1913 and US since then. Results: Using either HDI or HDI* gives a fairly rosy picture of welfare development since 1913 in the sense that poor nations have caught up with the rich, see Table 5. For example India has come up from a level of 0.055 to 0.439. It is the increase in life expectancy that drives this rise in HDI, but life expectancy improvements in the 20th century was largely independent from income. Furthermore it seems as if most poor nations today have a HDI* equal or above that of England in 1870. However, if we calculate the >value of life= in developing nations today as equal to that in UK in 1871 the income per head adjusted for their higher than UK 1870 life expectancy indicates income above that of UK in 1870. Next step in Crafts= analysis is to calculate revised GDP/head estimates adding >the value of life= and value of leisure. Value of leisure has a straightforward interpretation. At the margin a worker makes a choice between working an extra hour and enjoy the utility from consumption of the goods that extra hour buys and to use that hour as leisure time which also contributes to the welfare of the worker. The value of leisure is simply taken to be the average income per hour and added to the recorded income per head. The impressive fall in working hours in the 20th century adds to adjusted GDP. The >value of life= is more tricky to measure - and Crafts= exposition of the argument is not entirely clear. The basic idea is this. Different jobs have different health hazards and by implication different life expectancies. Workers in dangerous jobs are assumed to get a higher wage to compensate for the lower life expectancy and by measuring the size of that premium you can get a rough measure of the value of an extra year. It turns out that this calculation gives a strong effect: the benchmark calculation assumes that a ten percent increase in life expectancy will generate a 0.24 percentage points increase in adjusted GDP growth..