Understanding Economic Bubbles

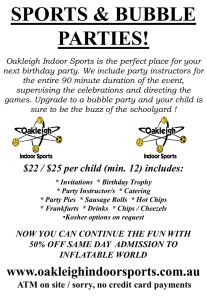

advertisement